One of the last neon signs on Main Street in Penticton was removed after the Elite Restaurant closed for good in 2018.

(DAN WALTON / iNFOnews.ca)

January 30, 2022 - 12:30 PM

- This story was originally published Jan. 22, 2022.

Penticton has always been a favourite destination for tourists from around the province, but it no longer attracts the massive crowds of wild partiers that it once did.

Over a century ago, folks would have been enjoying Charlie Chaplin films at the Empress Theatre on Front Street, which opened in 1914. Anybody around in 1939 could have gone to see Gone With the Wind on opening night at the Capital Theatre on Main Street. Decades later Penticton movie-goers had to catch their films at the Twilight Drive-In near the hospital, the Pine Drive-In to the south of the city, or at the Pen-Mar on Martin Street.

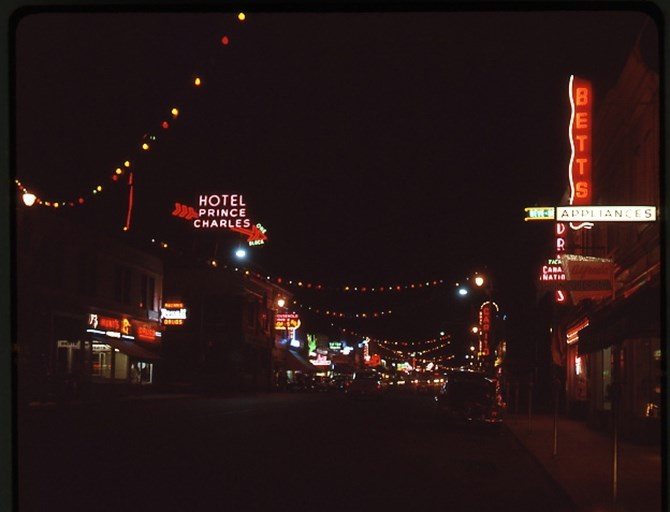

From the 1950s to 1970s, anyone cruising down Main Street found themselves underneath a sea of neon lights.

In the 1970s and 1980s, nightlife could have meant going to the discotheque, hanging out at a pool hall, or drinking at a hotel bar.

By the early 1990s, Penticton's reputation as a place to party may have reached its peak.

“Maybe ’89 to ’93 or ’94 were the intense years,” recalls former journalist John Moorhouse. “It would be wall-to-wall people on Main Street on weekends in the summer.”

A little too much fun was had on the B.C. Day long weekend in 1991, when rapper MC Hammer played a summer show in Penticton – one year after the release of his signature song U Can’t Touch This. The downtown streets were already packed full of partiers before the concert was finished.

“It was a different generation – a generation that was into the street parties,” Moorhouse said.

So when everyone at the MC Hammer show emptied onto the same streets, chaos ensued.

“Apparently there was a fight by the peach,” said Moorhouse, who reported on the riots at the time. “The RCMP tried to break it up and it got exasperated at that point.”

Tear gas was deployed and at least 80 people were arrested, according to the Washington Post, which covered the event.

READ MORE: Penticton’s iconic fruit once had a sibling that served ice cream in a nightclub

The authorities had to crack the whip after that. During the next two years on the B.C. Day long weekend, Moorhouse recalls a very strong police presence.

“The RCMP was inviting officers from around the province to bolster the local detachment,” he said. “That kind of petered things down.”

Archivist Gary McDougall from the Penticton Museum & Archives remembers the police even set up roadblocks for drivers entering Penticton during those years.

“The stronger police presence made you feel somewhat uneasy for a few years but then that dwindled,” he said. “Eventually they turned it into more of a welcome-to-Penticton, handed out brochures about what to do in town, and made it a friendlier thing.”

Tourism in Penticton took a hit when the Coquihalla Connector between Merritt and West Kelowna opened in 1990, and more more parts of the Okanagan opened up to tourists from the Lower Mainland. Prior to the Coquihalla Highway, travelling to Penticton was the path of least resistance for Vancouver tourists vacationing in the Okanagan.

And Highway 97 used to run down Penticton’s Main Street before the Channel Parkway was built in the 1980s.

“People thought the downtown and all its businesses were going to die because of the bypass, but of course it was okay,” said McDougall. “The truckers appreciated it, they could carry along without stopping.”

READ MORE: Celebration planned as latest downtown Penticton revitalization project is completed

During that period in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Max Picton was a young boy whose parents owned a campground. He remembers earning hundreds of dollars on long weekends by collecting empties that were left behind on campsites.

“When everyone was coming from the coast, Penticton was the spot,” Picton said. “I saw a little bit of that die off when the Coquihalla opened.”

Picton is now the owner of the Barefoot Beach Resort. He understands why some campers like to get rowdy to enjoy themselves, but he said the community’s attitude towards that kind of behaviour shifted over the past 30 years.

“At Barefoot we’ve had conflicts between noisy campers who wanted to party and other folks who are paying good money to park their RVs here. At the end of the day most businesses cater towards the group spending more money and causing less trouble.”

He noticed campgrounds began fading away throughout the Okanagan, and figures the seasonal businesses weren’t lucrative enough to prevent other ventures from displacing them.

READ MORE: Few hiccups from Penticton's 'beer on the beach' project

But despite losing some of the momentum from the 1990s, Picton still remembers Penticton having a vibrant nightlife in the 2000s.

“By the time I turned 19 the scene was still strong, but not as strong as it was the previous decade,” he said.

As a 20-year-old, he was working a day job with Coyote Cruises and evenings as a bouncer at a club called Night Moves on Main Street. During an extra-busy long weekend in August that summer, he remembers his boss from Night Moves demanding he come in at 7 p.m. that night, but he was too tied up dealing with scores of people who were floating the channel.

“He was like, ‘where the hell are ya we got a lineup around the corner, get here now!’”

A few years later, Picton got more involved in Penticton’s nightlife when he became a part-owner of Element Night Club, and later the general manager of the Best Damn Sports Bar on Martin Street. He remembers how much Toxic by Britney Spears and any single from the Black Eyed Peas got overplayed during those years.

“There would be lineups down the block outside of every club. People from the coast knew Penticton as a party city.”

But things have changed. The Parrot at the Lakeside Resort is the closest thing to a nightclub the city has left. Penticton is still a popular destination for tourists, but entertainment doesn’t last as late into the night as it used to.

Penticton's downtown was once a hotbed of neon signage.

Image Credit: Penticton Museum Archives PMA 3250

“One of the big things that I think really hurt the bar industry in general, was the introduction of cell phones,” said Picton. “You’d call somebody at home, if they weren’t at home, well chances are I'll probably run into them down at the bar… bars were a central gathering point where you would find everybody.”

Another contributing factor, he suspects, is the shifting trends in designer drugs. Decades ago when cocaine was the party drug of choice, it helped to promote drink sales. Bartenders were kept busy by patrons who would enjoy the cycle of doing a bump and then having a drink before hitting the dance floor.

“It’s not like we ever condoned any drug use but the reality is that it was there.”

As the years went on and ecstasy was introduced to the menu, Picton noticed a correlation with lower drink sales.

“Stuff like that costs $5 a pill, keeps people high all night, and then they don’t drink a lot of liquor,” he said, adding that people on ecstasy demanded a lot of tap water.

READ MORE: No noise is good noise in downtown Penticton

That type of audience would also demand name-brand Djs that could cost between $10,000 and $15,000 per night, said Picton.

“It became difficult for bars to remain exciting to crowds because our liquor sales would actually go down on those nights.”

While Picton remembers having “a hell of a good time” in his 20s, he feels like Penticton’s nightlife isn’t as rowdy as it once was because the community is maturing.

“I don’t think the shift in the industry is right or wrong, it’s just a sign of the times.”

As an example of the community maturing, he said wine tastings have traditionally been a popular choice for stagette parties, but many wineries are no longer welcoming them because owners want to keep the noise levels down.

And demographically, there are more senior citizens living in Penticton now than in the past.

“As more older retirees move into area, they wanted less and less of the party atmosphere,” he said.

Before Picton was running Element, that venue was known as Tiffany’s Nightclub, and it was first opened in 1977 by John Vassilaki, who is the current mayor of Penticton.

“The disco era was at its height,” Vassilaki said.

READ MORE: Back to school bush bashes a bad idea: Penticton RCMP

He remembers the first three or four years of Tiffany’s the most fondly, as everybody would dress to impress.

“If you were wearing jeans you could not come in.”

He said the amount of alcohol abuse and aggression were minimal during those early years.

“The disco era was a gentleman’s type of situation – ladies came and had a good time, fellas came and had a good time,” Vassilaki said.

“Society today is a lot different than it was, back in the 70s.”

Penticton's downtown core ablaze with neon and Christmas lighting on Dec. 16, 1969.

Image Credit: Penticton Museum and Archives PMA# 23294

He knows numerous couples that are still together today who met at Tiffany’s, and he said the club had top-notch entertainment. On some weekends, a radio station would even broadcast the music and entertainment going on at his club.

“Anyone who was anyone performed at Tiffany’s,” he said, adding that Brian Adams performed there three times in his early days.

Tiffany’s neon lights were among many that added vibrancy to Main Street.

“We tried to brighten up the downtown area. The neon lights and all the signs, they brightened up the streets so it looked like Vegas. It was very inspiring for the public to be downtown.”

His memories of Penticton’s nightlife aren’t as romantic after the 1970s.

“In the late 1970s, City Council – in their wisdom – wanted all those signs to be removed, only facial signs were allowed on the buildings downtown.”

And beyond Penticton, he noticed the evolving styles of music also impacted local nightlife.

“When rock ’n’ roll and hard rock came in after disco – society and the behaviour of people changed. The way they treated people changed. They lost respect. Lots of the fellas lost respect for the women.”

Vassilaki also noticed a big increase in physical confrontations, and not just at Tiffany’s.

But long before Vassilaki was in the liquor business, he remembers going into the Elks Hall for 50 cent rum-and-cokes as a 19-year-old. He and his friends weren’t old enough to get in on their own but they always found members to sign them in.

“We’d go there and have a good time with all our buddies,” he said. “They had a jukebox in their hall there.”

Back then, once young folks were old enough to drive, Vassilaki said it was common to be barrelling up and down Main Street, which was built for two-way traffic at the time, and there was a turnaround point where the Lakeside Resort is now.

READ MORE: Mule Nightclub to apply to stay open longer (2013)

The city’s last nightclub, The Mule, closed in 2018. Slackwater Brewing is currently operating out of the same location, and it is one of many micro breweries to open in Penticton in the past decade.

While Penticton’s nightlife has been toned down, Vassilaki said the city has remained a great destination thanks to the number of nearby wineries, the beaches at Skaha Lake and Okanagan Lake, as well as the longstanding success of PeachFest and the Penticton Vees.

“We are still as vibrant as we ever were but it’s a little different now.”

The Mule was the only nightclub in Penticton remaining before it closed for good in August 2018.

(DAN WALTON / iNFOnews.ca)

To contact a reporter for this story, email Dan Walton or call 250-488-3065 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2022