The Fintry Estates Manor House

Image Credit: Submitted/Fintry.ca

April 11, 2021 - 6:00 PM

The Okanagan’s history is littered with stories of remittance men, who were the younger sons of the British elite who were sent off to the Colonies with stipends to find their way in the new world while first-born sons inherited wealth.

One was Coutts Marjoribanks whose sister Lady Aberdeen built Kelowna’s Guisichan House for him in an effort to keep him out of trouble.

It didn’t work all the well as the home was known as a party house.

READ MORE: Ghosts of Kelowna partiers past heard between rows of ill-fated trees

Another might have been James Dun-Waters. He was destined to be just such a son but a “number of tragic deaths in the family precipitated him into the position of financial authority,” according to Dan Bruce, curator of Fintry Estates.

Dun-Waters ended up inheriting not only his father’s but his uncle’s fortunes at the age of 22. He still ended up coming to the Colonies but that was as an established member of the British gentry who came and created Fintry Estates, named after Fintry, Scotland.

That’s not to say he always played the gentry card when he went off to town.

Captain James Cameron Dun-Waters, 1915.

Image Credit: Submitted/Fintry.ca

“In Kelowna, at one point, he was sitting on a bench in City Park and was approached by a policeman and told to move on because he didn’t want tramps around here because he was dressed so roughly,” Bruce said. “He got up and moved on as instructed without saying anything at all. But that gave Kelowna a bad impression as far as he was concerned.”

Another time he was in a Vernon hardware store and asked if they had barbed wire.

“The young kid behind the counter said 'yes' but looked at him up and done and said: 'But do you have any money to pay for it?’” Bruce said. “Apparently Dun-Waters said he might have but he didn’t like the guy’s attitude so he walked out and walked down the street to the competition and ordered a boxcar full of barbed wire, which was the biggest hardware deal that ever went down in Vernon’s history.”

Dun-Waters bought the barbed wire out of necessity, not out of spite since the Fintry Estate encompassed more than 2,000 acres on the delta by Shorts Creek on the west side of Okanagan Lake.

He raised beef and dairy cattle, pigs, probably sheep and poultry, Bruce said. He also grew fruit on a commercial scale that he shipped by steamship from his own packing house.

Dun-Waters grew up in Scotland but later moved to England where he was a full-fledged member of the landed gentry with its fox hunting and such other sports. He developed a love of the outdoors, hunting and fishing.

He was invited to Canada by his Cambridge University buddy and future Governor General of Canada, Earl Grey.

“He likely arrived in Ottawa to a private and fairly ostentatious reception then off they went to the far west, probably with two or three cases of whiskey and one rifle,” Bruce said. “At some point, Dun-Waters would have seen the Okanagan and the delta and Shorts Creek. Whether it was his own concept or Grey suggested it: ‘Why don't you sell up and move here?’”

He did that, selling his shares in the Glasgow Herald and other assets.

Of great appeal was the tremendous drop in Shorts Creek as it came down the mountain, making it ideal for a “Pelton wheel” suitable for generating electricity. As well, there was a huge, flat delta to be cleared.

The Manor House in 1930.

Image Credit: Submitted/Fintry.ca

Dun-Waters bought up the land from a collection of settlers, likely including Thomas Shorts, the boat captain after whom the creek was named.

Just when that happened is not clear.

“At Fintry we have a portrait of Earl Grey that is autographed and the autograph includes the statement, ‘In memory of the 10th of May, 1909.’” Bruce said. “Based on that, in 2009, we celebrated Fintry’s 100th anniversary. I got through that day at Fintry without anybody asking me what happened on that day, May 10, 1909, which is a good thing because, the answer to that, 'I don’t know.'”

Bruce did check with authorities in Ottawa to see what Grey was doing that day but drew a blank. Records just show he was not in town.

In those days, there were no highways, just Okanagan Lake, so Fintry was not considered isolated in any way.

Dun-Waters built a manor house, complete with landscaped gardens, a 40-acre orchard, sawmill, additional residences for farmworkers, stables, four upland hunting lodges, a quarry, a roofed-in electrically lit curling rink, and one of the only circular (octagonal) dairy barns in the province, the Fintry Estates web site says.

This is the only octagonal barn in B.C.

Image Credit: Submitted/Fintry.ca

Dun-Waters was also unique in his treatment of his employees in a time when Chinese and Japanese workers often didn’t have their names recorded by their employers and weren’t allowed inside their homes.

“At Fintry, it didn’t matter what colour your skin was, if you did your work you got your pay, and that was it,” Bruce said.

Dun-Waters employed a Chinese cook and a Chinese butler. When he died, he left his butler $1,000.

“In 1939, that was serious money,” Bruce said.

Dun-Waters had two outdoor curling rinks and was a lifetime member of the Vancouver Curling Club.

Image Credit: Submitted/Fintry.ca

In the end, there was no inheritance to pass on to a first-born child since, despite two marriages (his first wife, Alice, died in 1924) he had no children.

He died in 1939 of cancer. Knowing his second wife, Margaret, did not want to run the estate he tried to sell it but, given that it was the Depression, found no buyers.

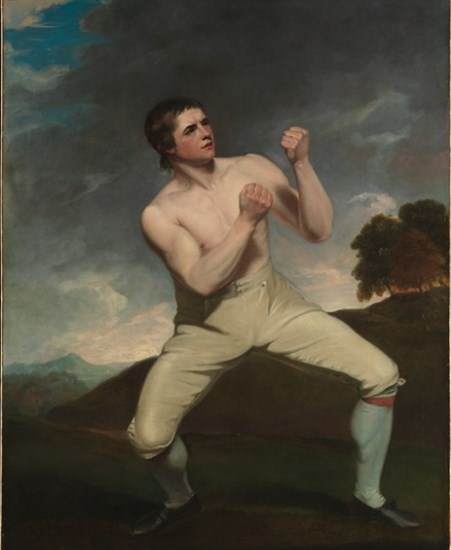

The 1788 John Hoppner Portrait of Richard Humphreys.

Image Credit: Submitted/Metmuseum.org

He sold it to the Fairbridge Farm School for $1. This was an organization that took British children to the Colonies to be raised and educated.

“There is some controversy about this, needless to say,” Bruce said. “There are, nowadays, all kinds of accusations of abuse, mistreatment and white slavery, you name it. I’m not saying that never happened. I’m saying nowadays the current mindset is to focus on that and overblow it.”

Some of the children chose to come to Canada. Some were living in the slums of London or Liverpool and had no real future.

“Others probably did have a future and it got changed,” Bruce noted.

By 1948, due to a lack of finances, the Fairbridge Farm School ceased to operate. Arthur and Ingrid Bailey bought the land in the early 1950s.

A 2007 Globe and Mail obituary of Arthur Bailey says he lived there until his death and, in the 1960s, he acquired the MV Lequime ferry and converted it to a mock paddle wheeler that he named the Fintry Queen.

READ MORE: The Fintry Queen is looking to ferry passengers on Okanagan Lake once again

When she moved to Abbott Street in Kelowna, Margaret Dun-Waters furnished her home from Fintry, including the 1788 John Hoppner's Portrait of Richard Humphreys, The Celebrated Boxer Who Was Never Conquered.

In 1951, she offered it for sale and it was snapped up by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

When Bruce later tracked it down, he asked for a photograph to mount at Fintry.

“They replied and said, what do you want it for?” Bruce explained.

“I said, for permanent exhibit at Fintry. And they said we don’t make our images available for permanent exhibits anywhere. So I responded to that by saying, yes, that’s fine and I don’t blame you but that painting was originally hanging in this house and, therefore I request and require a copy for permanent exhibit. They replied by email saying, got you, understood, no problem, digital copy on its way compliments of the Metropolitan Museum.”

Dun-Waters loved to hunt. This is his trophy room.

Image Credit: Submitted/Fintry.ca

Margaret Dun-Waters moved to Mission, B.C., where she died in 1980.

If there are other such artifacts around, it may be harder for the Friends of Fintry Estates to recover them in a similar fashion to the Boxer painting since their funding for a curator is coming to an end.

In 1995, former Kelowna city councillor Ben Lee convinced the Regional District of the Central Okanagan to pitch in $2 million to go with $5.7 million from the provincial government to buy the land and turn it into a provincial park as of April 30, 1996.

Over the years, the two levels of government and the Friends of Fintry Estates (which was formed in 2000) have worked together to restore, preserve and refurbish the historic site.

But, part of that relationship is ending after the regional district decided to cut its $39,000 annual grant to the society. It’s being phased out over three years, with the first one-third cut was made this year.

All that money goes to pay Bruce as curator, a job he’s held since 2002.

“What Dan does is tremendous,” Kathy Drew, president of the Friends of Fintry Estates said, pointing out it’s not just tracing the history and finding artifacts from the estate, but to educate the summer students who provide tours and change the displays to keep them fresh for returning visitors.

Funding sources don’t pay salaries so there is no easy way to replace that money other than to get the regional district to change its mind.

“A lot of them have never even been to Fintry,” Drew said “If they would come down there occasionally and just see what’s going on. To them, it’s just something they sign a cheque for and that’s it.”

Drew also pointed out that Bruce will be receiving a lifetime achievement award from Heritage B.C.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2021