This photo from the winter of 1949-50 shows the channel broken by ferries crossing Okanagan Lake. The wide spot is so two ferries can pass.

Image Credit: Submitted/Old Kelowna

January 16, 2024 - 12:00 PM

Don Knox remembers not only skating on a glassy smooth Okanagan Lake as a young child, but also on a nicely frozen Mission Creek.

“When we were kids – I can’t remember the first time, it would be about '53 or '54, I was just learning to skate – and the lake froze,” he told iNFOnews. “So we went out there and it was wonderful. It froze and there was no snow.”

He, and his parents before him, have lived on the shore of Okanagan Lake, just south of Mission Creek, for most of their lives.

He recalls that the lake not only froze enough for skating but boats struggled to break through it.

“Often, in the old days, the lake would freeze and the tug pushing the barge – it would go down to Peachland, Summerland and Penticton taking the rail cars on it – it would be going through and breaking the ice,” Knox said. “It would go up on the ice and you’d hear this crashing. It was quite loud.”

Skating on Okanagan Lake in the early 1900s.

Image Credit: Submitted/Old Kelowna

It's been reported, on the Old Kelowna Facebook page, that the winter of 1949-50 was the last time the lake froze over completely, not only across but end to end.

The ferries crossing from Kelowna to Westbank - sometimes with the assistance of dynamite - broke through the ice to keep it open. That gave a strong indication of how thick the ice was so people would drive their vehicles on it.

There were even stories of stock car races on the lake but, Knox said, that may be just an urban legend.

The ferries stopped in 1958 when the floating bridge opened.

But, Knox said, the tug pushing the barge continued working into the 1960s.

He recalls the lake freezing over all the way across near the bridge into the early 1980s but he, and others, can’t recall exact dates.

In fact, historian Bob Hayes wrote in a Lake Country Museum posting in 2017, that the lake is reputed to have frozen over completely at least once a decade and 12 times since 1900.

“This may be true but it invites sceptics clambering for proof that the lake froze that often,” he wrote. “Possibly the lake froze only in certain areas.”

The strongest evidence of the lake freezing over completely is during the winter of 1949-50.

That’s backed up by weather records that date back to 1899 in Kelowna.

The coldest mean monthly temperature ever recorded for January was -15.7 Celsius in 1950.

There were only eight Januarys in the last 122 years where the mean temperature was in double digits on the negative side of the freezing level.

The last time that happened was in 1979 when it averaged -11.4 C for all of January.

In the first half of the century it was in double digits six of those eight times, 1907, 1909, 1916, 1930, 1937 and 1950.

While it’s easy to say climate change is the reason for the warming winters, the real reason may be the dying of the Little Ice Age, Rob Young, associate professor of Earth, Environmental and Geographical Sciences at UBCO, told iNFOnews.ca.

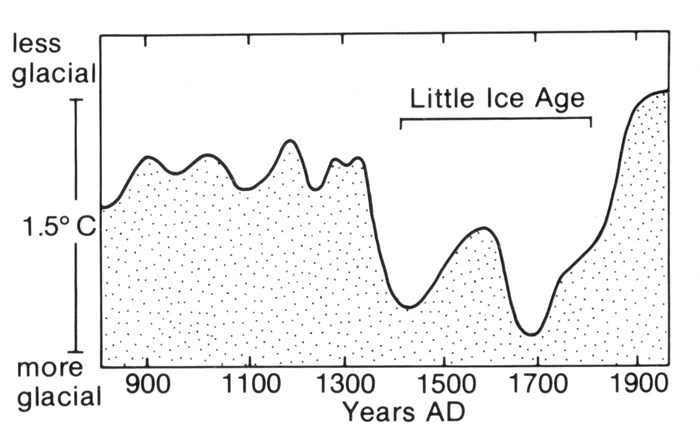

“If you look at longer time spans, over the last millennia, conditions deteriorated in the 1300s to the mid-1800s,” he said. “It was called the Little Ice Age and we’ve been climbing out of that ever since.”

A graph he sent shows a steady decline in glaciation since about 1700.

This shows glaciation over 1,000 years with the little ice age from the 1300s into the mid-1800s.

Image Credit: Submitted/UBCO

He’s not a climatologist so could not say how much of that warming is due to the Industrial Revolution that started in the later 1700s.

Bernard Bauer, Dean of Arts and Sciences at UBC, is more willing to put the blame more recently on climate change.

“The short answer is that the lake doesn’t freeze over anymore because of progressive global warming—of the atmosphere, oceans, land surface and, not surprisingly, lakes,” he wrote in an email to iNFOnews.ca. “The longer answer involves thinking about the energy budget of lakes (i.e. the heat balance). Gradually, our lakes (and oceans) are storing more energy than they did, say 100 hundred years ago.”

The lake is now getting warmer each summer so more extreme cold is needed to freeze it in the winter, something that just doesn’t happen anymore, he wrote.

Automobile pollution from bigger cities like Kelowna gets trapped during the frequent winter inversions, helping warm the local winter temperatures, Young said.

And, there is now treated sewage flowing into the lake. Even though those amounts are small compared to the overall size of the lake, they may be having just enough of an impact to stave off freezing.

Young could not say what kind of sustained cold temperature would be required before Okanagan Lake freezes as there are variabilities, like wind, that have an impact.

“Water is easily mixed,” Bauer wrote. “Wind will disturb the water surface and make waves, which induce mixing of surface water with deeper water. That also distributes the energy from the sun at the water surface downward.”

Water is also “very peculiar” in that its maximum density is at 4 C.

“Warmer water is less dense (i.e. ‘lighter’) but so is colder water,” Bauer wrote. “The four-degree water settles to the bottom of the lake basin. When you think about it, this is really interesting and critical to understand. Because you have to get the entire mass of lake water down to 4 degrees BEFORE you can induce any freezing at the surface.”

That repeated turning over of the lake is probably what causes the Ogopogo wave that is sometimes believed to be the legendary lake monster, Young said.

All those factors make it more and more likely that Okanagan Lake will not freeze over completely, or even side to side, any time soon.

“You would need a fantastically cold and long winter, which is becoming increasingly unlikely with global warming,” Bauer wrote.

— This story was originally published on Dec. 9, 2022.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2024