Walhachin in the early 1900s.

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

October 15, 2023 - 6:00 AM

Drive Highway 1 between Kamloops and Cache Creek and it’s impossible to miss the large Walhachin Welcomes You sign.

The drive down the windy road through green fields, across the Thompson River and past through a mix of dry hillsides and more green field to the actual community of Walhachin may be a disappointment as there is only a small cluster of older homes around a much larger Soldiers Memorial Hall.

Yet this was once the site of a promising frontier haven for the spoiled and rich and outcast sons of English gentry.

Walhachin Hotel.

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

Some blame its demise on the First Great War.

“The hardships brought on by the First World War stopped Walhachin’s prosperity in its tracks,” a 2015 article in the Merritt Herald flatly states.

“When war broke out in 1914, ninety-seven of Walhachin’s one hundred and seven men enlisted with the Canadian or British forces,” states an article in Gold Country BC. “The few men and women that remained could not maintain the orchards and flumes. Many of the men were killed during the war, and those who returned found the colony in hopeless disrepair.”

READ MORE: Canneries had a short but vital heyday in Kamloops, Okanagan

That bears only a slight resemblance to the reality of the situation as portrayed in the 1967 UBC masters thesis of Nelson Riis, who went on to become the Kamloops-Shuswap NDP MP from 1988-2000.

“A settlement, at that particular site, based on agricultural economy, could likely never have endured as a self-supporting entity, regardless of the level of expectation held by the settlers,” was one of his key conclusions.

Construction tents.

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

The thesis traces the origins of the area from its early ranching days, through the very short glory days of 1908 to 1914 and to its ultimate demise in 1922.

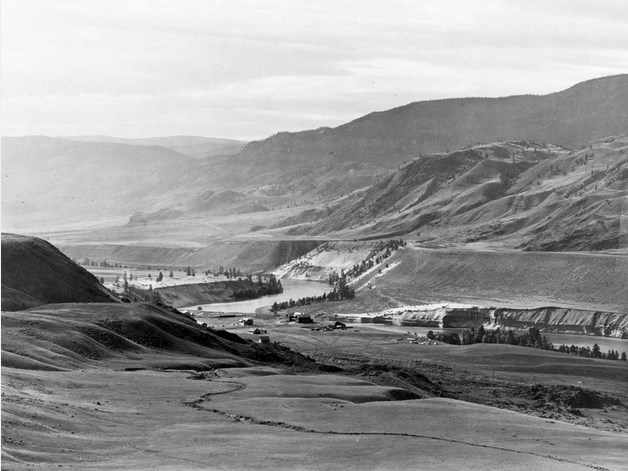

Wahachin covers 5,000 acres stretching for seven miles on either side of the Thompson River and is about 1.5 miles wide. It is about 56 km east of Kamloops and 28 km west of Cache Creek.

Excavating main irrigation ditch.

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

The lower lying land along the river was used by Interior Salish peoples as winter quarters.

“Fishing conditions were particularly good at Walhachin with the large oxbow and expanses of backwater creating not only good fishing but a suitable environment for waterfowl and excellent autumn hunting,” Riis wrote.

But, as with most of Canada’s history, the First Nations were pushed onto reservations after Europeans moved in.

READ MORE: How Europeans distorted the true names of Kamloops and the Okanagan

Their wintering sites were ruined when gold miners moved through, starting in 1858, and the winter homesites became part of a major cattle driving route through to the Barkerville gold fields.

Ploughing for the orchards

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

“Chief Ceciasket’s tribe, inhabiting the territory around Walhachin, consisted of 62 families with a total population of only 122 in 1868 (perhaps indicating the consequence of the 1862 smallpox epidemic),” Riis wrote.

“Although the tribe owned 28 horses and 10 head of cattle, the cattlemen who began moving permanently into the valley apparently had no intention of sharing good winter pasture with the Indians. Consequently, the Deadman’s Creek Reserve was surveyed in 1868 to provide a new home.”

The settlers named the area Sunnymede but changed it to Walhassen (later Walhachin) when the CPR built a rail station there around 1909.

The First Nation meaning of Walhassen was ‘land of round rocks’ but, because the creators of Walhachin were all about the land speculation business, they claimed it actually meant ‘abundance of the earth’ or ‘bountiful valley.’

READ MORE: Harper Ranch battled with 'Kamloops First Nation' before amassing land holdings

The fields of bunchgrass that made the area prime grazing land soon gave way to sagebrush and cactus because of overgrazing.

In the 1880s Charles Pennie created a ranch with a two-acre orchard, irrigated by water from Brassey Creek, that became the foundation for Walhachin.

Thompson River Valley

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

“He had chosen the orchard site well as the soil was the most fertile in the area, virtually stone free, suitable for furrow irrigation and protected by a windbreak,” Riis wrote.

“This productive orchard was misinterpreted by C.E. Barnes, an American land surveyor working out of Ashcroft, as being representative of the agricultural potential of the whole valley. Considering that fruit farming was just beginning in the Okanagan Valley and BC was caught up in an irrigation boom, it is not surprising that Barnes saw an opportunity for a speculative venture.”

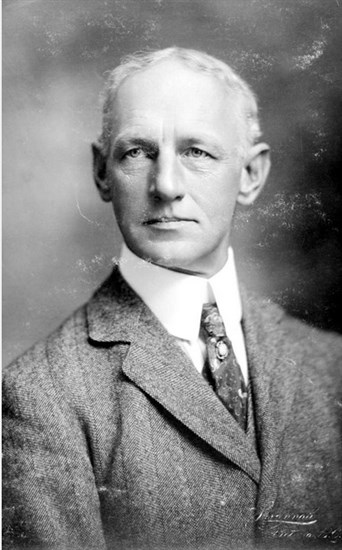

Charles E Barnes, 1915.

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

Pennie died in 1900. In 1908 his widow sold the ranch, through Barnes, to the London-based BC Development Association for a reported $229,400, including buildings, livestock and leased land, Riis wrote, although the actual price was never publicly disclosed.

The association, with Barnes as its agent, set about developing a town with 150 lots and 25 acres planted with grass “create a lush appearance in contrast with the sand and sagebrush,” Riis wrote.

Irrigation systems were built on both sides of the river and the land was marketed to “either sons of wealthy British families who were finishing their public schooling or military and government personnel about to retire on pensions. Most purchased the land sight unseen and, upon arrival, recognized that the valley was not as ‘bountiful’ as the promoters had indicated.”

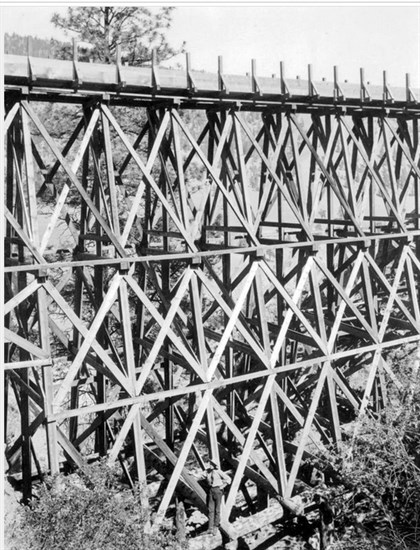

Trestle on Snohoosh fume

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

There-in lay the root of the fledgling community’s downfall.

Certainly the climate was not best suited to fruit growing with scorching hot, dry summers and some terribly cold winters. Plus the soil was not all that good.

The real problem, however, was the settlers' total lack of not only farming knowledge but also their unwillingness to learn either from neighbouring communities or schools of agriculture, not to mention the shortfalls of the marketing association.

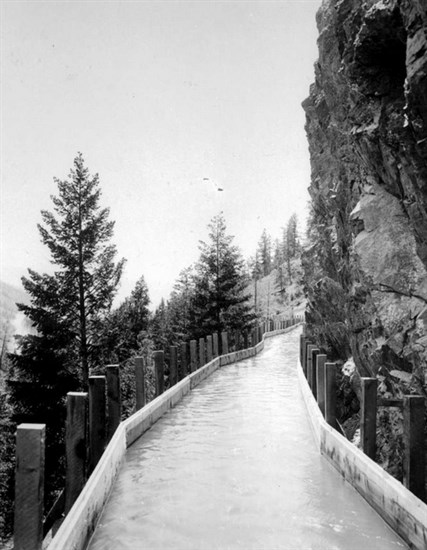

Snohoosh flume att the cliffs

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

As soon as the BC Development Association bought the land, it transferred Sir Talbot Chetwynd, who was manager of their 111 Mile House Ranch, to Walhachin to move the large herd of Shorthorn cattle off the Pennie Ranch.

“Chetwynd was the first representative of the BC Development Association to begin work on the site and may be regarded as the most qualified agriculturist that ever settled at Walhachin," Riis wrote. “It is significant that the most skilled settler to live in the orchard settlement had four years of varied experience with livestock.”

That is to say, no background in fruit farming.

A wide variety of fruit crops was tried, including cherries, pears, apples, peaches, plums and apricots but, by 1914, only apples survived the harsh climate and those were a long way from bearing an economical crop.

Old flume in 1977

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

In some ways, it’s no surprise that the community could be marketed as a fruit growing haven since the province, at that time, was boasting that apples could grow as far north as Hazelton in the Skeena River Valley.

But the failure of Walhachin really boiled down to the nature of the settlers who were more interested in a social life full of concerts and balls or sporting events than farming.

“None had any knowledge of farming practices and their willingness to learn is exemplified in that only two men (out of about 100) ever attended the winter courses in horticulture offered at the Pullman Technical College in Pullman, Washington,” Riis wrote.

READ MORE: The history behind this century-old abandoned church in the Shuswap

“There were large numbers of single men, most had more than adequate finances and virtually none had any commitments at Walhachin during the winter. Therefore, all had the opportunity to attend the College if they desired. The fact that only two men attended leaves one to suspect that, for most, the social life available at Walhachin was more appealing than studying horticulture.”

The two who did attend the College were the last to leave their estates after the war.

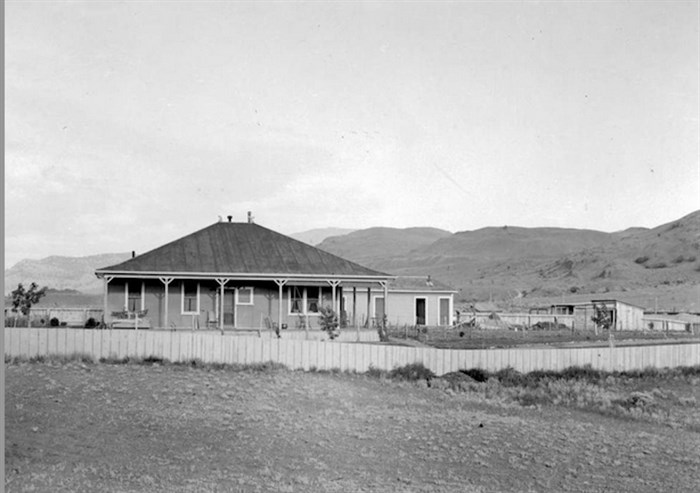

Ranch House

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

Most of the farming was actually done by Chinese and First Nations workers.

Give the failure of many fruit varieties, the settlers turned to planting vegetables between the rows. But there, too, they lacked any skills at all.

“Their major attempt at adjustment was, eventually, to plant as many varieties as possible to see which thrived best,” Riss wrote. “This resulted in duplication of testing already done by their neighbours and necessitated more replanting than should have occurred because the frozen tender varieties had to be replaced by those more hardy. The duplication happened since the settlers had little contact with their neighbours.”

READ MORE: iN VIDEO: How 'Canada's biggest water system' took Vernon from cattle to fruit

The declaration of war came as a relief to the single men. While their ties were to the old country and they wanted to serve and they had been training for the previous two years in Walhachin and Vernon, they really were looking for an escape from a community they had, essentially, been exiled to and where there were few single women.

Contrary to some reports, there was not a mass exodos of 100 of the 107 adult men from the community when the war broke out.

The Walhachin Squadron, of 40 single men, left on Aug 27, 1914.

That left behind the older and married men.

Irrigating an onion crop

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

“With a decline in funds from England, a weakening leadership and a labour shortage, the orchards began to deteriorate,” Riis wrote. “This led to a number of family men volunteering and, as more men left, the settlement began to decline through neglect of homes, services and the water system.”

By 1918, the 100 men had left.

Again, contrary to some reports, Riis wrote that very few men were actually killed in the war and most did return to Walhachin but, “seeing the condition of Walhachin, soon made other plans.”

READ MORE: Spiritualists, Japanese warlords and mispronounced words: Where the Okunaakan got its names

It wasn’t until 1917 that enough apples could be grown for shipment but that only lasted for another year.

Thunderstorms in 1918 flooded 1.5 miles of irrigation ditches with mud and gravel and wiped out a number of flume sections.

While the irrigation system was replaced by the following year, most of the fruit and vegetables were wiped out by drought.

Four year old orchard

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

Along with all of this, the BC Development Association went into bankruptcy and the land was bought by the Marquis of Anglesey, who had his own financial problems.

He replaced Barnes with Chetwynd as the manager. Not only did Chetwynd not know much about farming, he wasn’t much good at practical matters either.

He, for example, supervised the laying of tarred roofing paper to line two miles of flumes. He overlayed the lower sheet on top of the upper sheets so, when the gates were opened, the water ripped out all the lining.

By 1922, all the original British settlers were gone.

“Settlers came to Walhachin for as many reasons as there were settlers but, for most, had they had a choice, few would have come,” Riis wrote.

“The young men usually had one of three backgrounds: one of repeated failure or behavioral problems at school, one of personal scandal or legal difficulties or one of military service expulsion. Generally their families were at a loss as to what to do with them so the boys were encouraged to go overseas to manage the family’s newly acquired properties at Walhachin.”

“Indeed, the quality of settler at Walhachin left much to be desired; little willingness to work, lack of useful skills, little motivation to succeed or, as one informant stated, ‘Walhachin was a catch-all for rejects.’”

Image Credit: Submitted/Royal Museum BC Archives

Still, the community did not die.

Cattleman Harry Ferguson moved cattle in for winter grazing in 1940 and bought the land a few years later.

Modern irrigation has allowed for forage crops to be successfully grown and there are about 40 permanent residents these days. A number of original buildings remain with the Soldiers Memorial Hall continuing to hold social events.

There is even Friends of Walhachin Facebook page and, since 1916 (except for COVID years), the community has hosted an annual Walhaschindig with live music, games and food.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above. SUBSCRIBE to our awesome newsletter here.

News from © iNFOnews, 2023