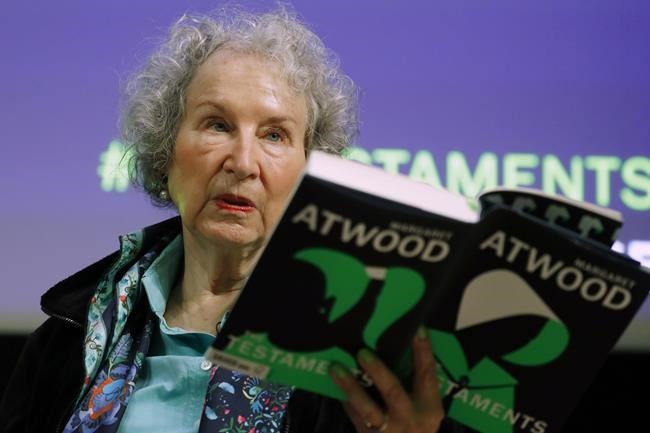

FILE - Canadian author Margaret Atwood holds a copy of her book "The Testaments," during a news conference, Sept. 10, 2019, in London. Filippo Bernardini, who impersonated hundreds of people over the course of the scheme that began around August 2016 and obtained more than a thousand manuscripts including from high-profile authors like Margaret Atwood and Ethan Hawke, was sentenced Thursday, March 13, 2023, in Manhattan federal court, after pleading guilty to one count of wire fraud in January. Bernardini was sentenced to time served, avoiding prison on a felony charge that carried up to 20 years in prison. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant, File)

March 24, 2023 - 3:45 PM

NEW YORK (AP) — It was the stuff of novels: For years, a con artist plagued the publishing industry, impersonating editors and agents to pull off hundreds of literary heists. But the manuscripts obtained from high-profile authors were never resold or leaked, rendering the thefts all the more perplexing.

The Thursday sentencing of Filippo Bernardini in Manhattan federal court brought the saga to an end and, with it, finally some answers. After pleading guilty to one count of wire fraud in January, Bernardini was sentenced to time served, avoiding prison on a felony charge that carried up to 20 years in prison. Prosecutors had asked for a sentence of at least a year.

Bernardini, now 30, impersonated hundreds of people over the course of the scheme that began around August 2016 and obtained more than a thousand manuscripts, including from high-profile authors like Margaret Atwood and Ethan Hawke, authorities have said.

In an emotional, four-page letter to Judge Colleen McMahon submitted earlier this month, Bernardini apologized for what he characterized as his “egregious, stupid and wrong” actions. He also offered insight into his motivations, which had long stymied victims and observers alike even after his plea.

He described a deep love of books that stemmed from childhood and led him to pursue a publishing career in London. While he obtained an internship at a literary agency there, he wrote, he had trouble securing a full-time job in the industry afterward.

“While employed, I saw manuscripts being shared between editors, agents, and literary scouts or even with individuals outside the industry. So, I wondered: why can I not also get to read these manuscripts?” he recounted.

He spoofed an email address of someone he knew and mimicked his former colleagues' tone to ask for a manuscript that had yet to be published. The success of that deception turned his quest for ill-gotten books into “an obsession, a compulsive behaviour.”

“I had a burning desire to feel like I was still one of these publishing professionals and read these new books,” he wrote.

“Every time an author sent me the manuscript I would feel like I was still part of the industry. At the time, I did not think about the harm I was causing,” he added. “I never wanted to and I never leaked these manuscripts. I wanted to keep them closely to my chest and be one of the fewest to cherish them before anyone else, before they ended up in bookshops.”

As part of a bid to avoid prison, Bernardini's lawyers also submitted more than a dozen letters to the judge from his friends and family. In a novelistic twist of sorts, among them was a letter from a victim — writer Jesse Ball, the author of “Samedi the Deafness,” “Curfew” and “The Divers' Game.”

Bernardini impersonated Ball's editor to convince the writer to send several unpublished manuscripts, Ball said in his letter pushing for leniency. Decrying the state of the industry as “more and more corporate and cookiecutter” and referring to the crime as a “caper” and a “trivial thing, frivolous thing,” Ball argued that “we must be grateful when something human enters the picture: when the publishing industry for once becomes something worth writing about."

“For once a person cared deeply about something—what matter that he was an interloper? You cannot imagine the soul crushing boredom of run-of-the-mill publishing correspondence,” Ball wrote, adding that he suffered no harm from the thefts other than some confusion. “I’m grateful that there is still room in the world for something facetious to occur now and then.”

In weighing arguments from the prosecution and defense, McMahon pushed back on the idea that the crime was victimless, with New York magazine's Vulture — the publication that brought the mystery to public attention with a 2021 story called “The Spine Collector” — reporting that “she was especially moved by a letter from a literary scout" who had been accused of Bernardini's crimes. Vulture also reported that McMahon expressed sympathy for Bernardini in light of a new autism diagnosis, but said it didn't excuse the threats he made in some correspondence. But she concluded a prison sentence wouldn't help the victims.

Bernardini — an Italian citizen and British resident who was arrested at John F. Kennedy International Airport in January 2022 — will be deported from the U.S. Court documents show he asked to be deported to the United Kingdom, where he lives with his partner and dog, with Italy as the designated alternative.

As part of his guilty plea, Bernardini agreed to pay $88,000 in restitution, which court documents show will go to Penguin Random House.

“The cruel irony is that every time I open a book," Bernardini wrote of his one-time passion, “it reminds me of my wrongdoings and what they led me to.”

News from © The Associated Press, 2023