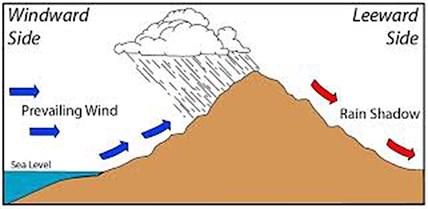

A weather phenomenon known as a 'rain shadow,' created by mountains to the west of B.C.'s interior valleys of Nicola, Thompson and the Okanagan is a big factor in creating the dry climate these areas are known for.

(STEVE ARSTAD / iNFOnews.ca)

May 20, 2020 - 7:30 AM

Interior valleys of the Okanagan, Thompson and Nicola get more sunshine, less rain and are hotter and drier than nearly any other region in Canada.

And while the southern prairies are singled out for hours and days of sunshine — largely because of clear winter skies we often don't enjoy — our valleys are between vast mountain ranges.

Our valleys owe a big debt to the pile of rocks known as the Cascade range, lying between the interior valleys and the Pacific coast, to create our mountain oasis. It's why we have orchards and grapes and plentiful produce and why thousands of Canadians seek refuge from their weather (pandemics aside).

These dry valley floors lie in what is known in meteorological terms as a 'rain shadow.’

The phenomenon is created by the high mountains of British Columbia’s western interior as they strip moisture from incoming weather systems originating in the Pacific Ocean.

Elevation changes and their effect on air pressure also plays a role in the valley’s climate.

Environment Canada meteorologist Bobby Sekhon says the valleys gets most of their weather systems from the west during the winter months in what is generally a westerly or southwesterly air flow.

“British Columbia’s major mountain ranges are oriented in a north-south direction, with weather systems approaching from the west or southwest. As air rises over the mountains, the moisture in the air condenses and forms precipitation which falls on the windward, or western slope of the mountains,” he says.

Sekhon says the Coquihalla Highway provides a good example in illustrating where most of the precipitation falls.

“We’re aware of how much snow can fall on the Coquihalla over the winter compared to what falls on the valley floor. As the system moves into the Thompson - Okanagan, there isn’t much moisture left,” he says.

Air pressure also plays a role in defining the region’s climate.

Sekhon says on the eastern slope of the mountains there is a ‘downslope’ effect which also wrings moisture out of the system.

“As the air sinks downward, it warms up and dries up,” he says.

Sekhon says in spite of the rain shadow, the region doesn't quite qualify for desert status.

“Penticton’s annual precipitation is 332 mm. That compares with Anaheim, California, at 340 mm annually, which is a semi-arid climate,” he says.

There are other statistics to back up our reputation for being warm and dry places, nonetheless.

Kamloops and the Okanagan's major cities- Penticton, Kelowna and Vernon - rank first, scond, third and eighth for the most hot days in Canada, and Kamloops, Kelowna and Penticton rank second, third and fourth for the most sunny days in warm months in Canada.

Penticton is fourth when it comes to having the most clear skies in summer, while Kelowna ranks eighth in Canada, according to data from Environment Canada.

Kamloops is ranked the second driest city in Canada at 278.98 mm while Penticton is ranked fourth at 332 mm. Only Whitehorse is drier than Kamloops, at 267.41 mm.

Compare those figures with, say, Chilliwack which receives 1787.8 mm annually.

University of British Columbia Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences Associate Professor Phil Austin says it’s all about air pressure.

When those Pacific frontal systems hit the mountains, air is physically forced up by the slope.

“It can’t go into the ground, so it has to go up. As the air rises, it’s surrounded by air at lower pressure, so it expands, colliding with other molecules that are receding away from it, like hitting a bumper car that is moving away from you, it slows the molecules down,” he explained in an email.

Austin says the windward (west) side of the mountains condense out water vapour and rain because the rising air is also cooling.

Once over the summit, the air comes down as a warm, dry chinook wind because the cloud water that would have evaporated and cooled the air on descent is no longer present.

Austin says the one of the benefits of the rain shadow is California-like weather in the Thompson, Okanagan and Nicola.

"California is a Mediterranean climate because it's under a subtropical high pressure zone that is sending warm/dry air downward and evaporating clouds. A mountain range that causes a chinook does exactly the same thing to the land that is on its lee side," Austin says.

The pattern repeats itself as these weather systems move into the Kootenays, where, due to the nature of the topography, the impact on valley bottoms is more isolated and confined to microclimate pockets.

The rain shadow effect is not unique to the Okanagan. According to Wikipedia, there are several areas along the North American and South American coast that have similar weather systems impacting similar topography, such as the Atacama desert, beyond the Chilean Andes.

The east slopes of the Coast Range in central and northern California also creates a rain shadow effect in the San Joaquin Valley.

Regions influenced by the rain shadow effect can be found in most parts of the world.

The rain shadow effect is what gives the Thompson, Nicola and Okanagan valleys their dry climates.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Wikipedia

To contact a reporter for this story, email Steve Arstad or call 250-488-3065 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to tips@infonews.ca and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2020