Please Bring Me Home is a national non-profit organization of volunteers who search for missing persons.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED/ Please Bring Me Home

June 17, 2024 - 7:00 AM

Missing person cold cases across the country are being solved by a passionate group of volunteer members of law enforcement, retired investigators and people with forensic experience.

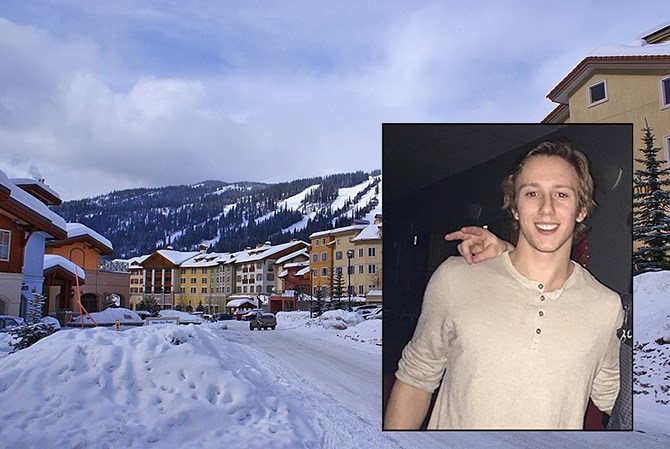

Some of those cases are in BC and include Ryan Shtuka, a young man who went missing from Sun Peaks in 2018.

“We’ve been working on Ryan’s case since he went missing,” said Please Bring Me Home executive director Nick Oldrieve. “We’ve received several anonymous tips on his case this spring.”

The volunteer team is working on 100 missing persons cases across the country and with the help of cadaver dogs and ground penetrating radar experts, has solved 36 cold cases within the last decade.

Interviewing suspects, wrestling with law enforcement and utilizing new technology are just a few of the things the team does to find the missing.

“We work on cases that are inactive, where there is nothing to go on, where media releases from police stop and a family doesn’t know where to turn,” Oldrieve said. “In my opinion, it doesn’t take long for a case to become inactive.”

Ryan Shtuka went missing from Sun Peaks Resort near Kamloops in 2018.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED/Wikimedia Commons and B.C. RCMP

Oldrieve’s career of searching for the missing began in Ontario in 2011 when he was working on a crisis team finding foster kids that ran away. The following year he moved to another city and sparked a similar initiative with a couple of others.

In 2016, the small team located a girl who had been missing for three weeks. Around the same time, by accident, Oldrieve stumbled upon the cold case of Lisa Maas, a woman who’d been missing from the same city for 26 years.

“I put an ad in the paper that the woman was from our city and to please come forward with information,” he said. “It snowballed from there, people and families of other missing people began communicating with us. People wanted to join the search team: consultants, investigators and retired members of law enforcement.”

The small team decided to expand operations across the country in 2018.

Maas’ case is still cold, however members of Oldrieve’s organization spoke to the primary suspect in her case over the past year.

“It’s obvious to us he’s the one responsible for her disappearance and is unwilling to assist, even if he has a deal in front of him. We talked him into talking to the police without a lawyer, the first time in 35 years since he spoke to law enforcement. The police declined to interview him. I don’t understand why.”

Oldrieve said police agencies can be difficult to communicate with but it varies across the country with some agencies happy to accept free information from the team, while others are leery of the team talking to witnesses and suspects.

“Law enforcement has to focus on justice, they can’t use methods to locate a missing person that could contaminate the possibility of a conviction. We will. It’s more important, ask any family members, that they’re found than it is justice.”

Missing Kamloops woman Shannon White with her dog, Buddy.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED/ Facebook

Oldrieve’s team knocks on doors along with cadaver dogs on leashes and asks residents for permission to search properties. They invite residents to come along and provide a report of the search afterward.

“We’ll say what we need to say to suspects in order to get them to communicate where these people are. If we speak to a suspect, it’s very orchestrated and we make sure law enforcement is aware it’s what we’re doing.”

The team does not operate on the same parameters as law enforcement, they don’t have as much red tape and don’t need to get search warrants.

Oldrieve said sometimes the team’s actions don’t jive with law enforcement.

“Some police agencies are willing to share search maps with us, of previously searched areas, but it takes a lot of begging,” he said.

“When it comes to interviews and theories, we’re never going to get that from police but that’s OK, it’s important we reach our own conclusion and if it matches their conclusion, it only adds credence to the case.”

READ MORE: Body of abducted woman found in Lumby area

The focus for Please Bring Me Home is on closing cold cases, but the team members have assisted in more current cases as a preventative measure.

“If nothing active is happening for a person missing for a week and the family asks for help, we step in for fear it will become a cold case if we don’t."

In a few days, team members will be conducting an intricate search for a fisherman that recently went missing on Lake Huron.

“We believe he has washed ashore but its 97 kilometres of shoreline and our fear is if we don’t locate him soon, he’ll be gone on the lake for good and will never wash up.”

READ MORE: Vernon woman found dead leaves behind two daughters

Most of the solved cases involved people who ran away, but seven of the missing people were found deceased during searches.

“As soon as we find skeletal remains or a body, we make sure we know where we are, we slow down, mark a trail out to the road and call the police and then lead them back there,” Oldrieve said. “You don’t want to call the police and not know where you are. They come, take over the scene and their team comes out and does the rest.”

With increasing DNA technology, it’s getting easier for law enforcement to solve cold cases.

Oldrieve’s team buys an Ancestry DNA kit, meets with a family member of the missing to collect DNA and sends it to the company. After several weeks, the DNA file will be listed on Ancestry. The team puts the file into an online database that will attempt to make a match with over one million other DNA files.

“If the person ran away and started a new life there is likely going to be familial connections on there, we start there,” he said. “Police take the DNA file off the database and upload it into their database to check against unidentified remains.”

READ MORE: 'Callous and cowardly': Ashley Simpson's murderer gets life in prison

When asked how the drug crisis has changed search operations, Oldrieve said a huge number of recent cases are of missing drug users.

“So much so it has to be a question on our intake process with families now, if there a history of drug abuse,” he said. “Two young men we located deceased died at the same time in a ditch and it was just bad drugs.

“There has been a shift in families calling in saying the member is addicted to drugs and fearing they’ll overdose somewhere alone. We’re trying to find someone who would go anywhere, into a tree line, a ditch, walk into the woods or on a sidewalk, where do you start looking?”

When asked what trends he is seeing in the First Nations population, Oldrieve said there is a lot of trust that needs to be built between First Nations communities, helping organizations and law enforcement.

“These communities are not reaching out to us, we don’t have many cases from that background, trust needs to be built and its up to us to bridge that gap.”

The organization is working on cases in every province except for Prince Edward Island. Investigators are located in multiple provinces and can work cases from a distance guiding crews on the ground.

READ MORE: Family of missing Merritt murder victim overwhelmed with rumours, questions

Every volunteer who joins the team is given one or two cases to research, so they become the experts of the case.

There are currently 30 active volunteers and more are needed, including in BC.

“We have top level cadaver dog teams and ground penetrating experts out west that go at the drop of a hat, but we need more volunteers. We need people who are committed and have persistence, and a high level of professionalism."

It has been over six years since Ryan Shtuka went missing from Sun Peaks Resort, but Oldrieve said his team still fields and investigates anonymous tips about his disappearance.

READ MORE: JONESIE: How Canadian news became victims in its own story

Shannon White was 32 years old when she went missing from her Kamloops home on Nov. 1, 2021. While Oldrieve’s team has completed an intake form for her case, they don’t currently have an active investigator working on it because they need more volunteers.

Oldrieve said his team consults with a man in Kamloops who has decades of search and rescue experience, and has been searching the Kamloops area for Shtuka and White with his trained search dog for the past few years.

Currently there aren’t any cases from the Okanagan listed on the Please Bring Me Home website, however there is a form available on the site for families of missing loved ones to fill out.

“Anyone who knows of a missing person case in BC can go through the intake process and we'll follow up,” Oldrieve said.

He encourages anyone with tips or any information on a missing person to call the anonymous tip hotline at 1-226-702-2728.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Shannon Ainslie or call 250-819-6089 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above. SUBSCRIBE to our awesome newsletter here.

News from © iNFOnews, 2024