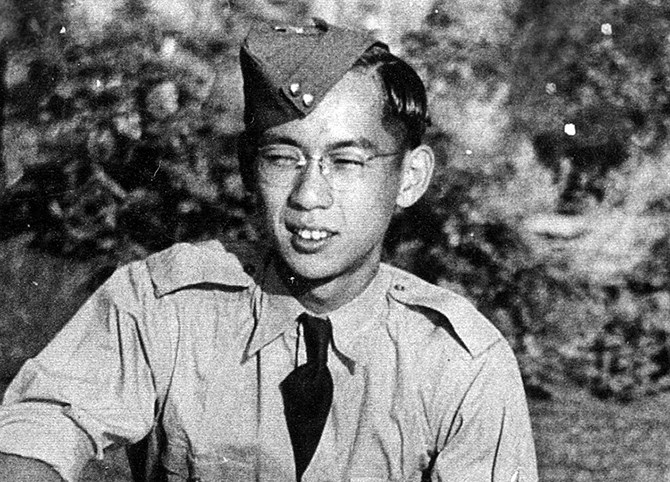

Henry Albert (Hank) Wong was the last of a group of 13 elite Asian Canadian soldiers who trained for a covert, special operations assignment known as Operation Oblivion on the east shore of Okanagan Lake north of Naramata, in 1944.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Veterans Affairs Canada

November 11, 2019 - 12:01 PM

The last survivor of a special covert World War II force with historical ties to a lonely stretch of Okanagan Lake shoreline passed away recently in London, Ontario.

Henry Albert Wong (Hank) died Oct. 10, 2019, in the southwest Ontario town just a few weeks shy of his 100th birthday.

Wong, a proud Chinese Canadian veteran of World War II, was part of a covert force known as “Operation Oblivion” and spent four months late in World War II training for the mission at a place now known as Commando Bay on Okanagan Lake north of Naramata.

Commando Bay north of Naramata on Okanagan Lake in 1944.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Rick Wong

Wong’s Okanagan connection began in 1940 when he enlisted in the Canadian army where he served with the Kent Regiment until he was recruited for Operation Oblivion in 1944.

As a Sea Scout in his youth, Wong first tried to join the navy but was rejected because of his race. He was successful in joining the army, however, and was stationed in New Westminster.

According to a Toronto Star article written last year and posted on the Chinese Canadian Military Museum website, Wong was recruited to Operation Oblivion while on leave back in Ontario. He was helping his sister run her restaurant in Palmerston one day when a diner came in, ordered fish and chips and lingered in the diner until closing. He then identified himself as British Intelligence personnel and asked Wong if he was interested in returning to active duty.

Wong was flown to Vancouver where he was recruited for the operation.

Wong’s son Rick said his father had long lasting memories of his training days on Okanagan Lake.

“He had quite a lot of anecdotes about Penticton and Commando Bay,” he said earlier this week. "Because they trained there for a long time, they actually raised chickens on the small island nearby. They used to call it Chicken Island. They would put chickens on there, and not have to watch them because it was surrounded by water."

Rick also recalled his father talking about how the commandos used to fish.

“If it was slow fishing with hook and line, they had all these detonators lying around. One of them got the idea to fish with explosives. They’d toss a detonator in and the boat would be surrounded by concussed fish,” Rick says.

Towards the end of training the commandos had a pile of unused bombs and explosive material. They put them together to stage a ‘show’ for a general who was coming to review them.

“The explosives were set up all along his route as he came up the lake from Penticton. They were blowing up these things on the hills above the lake and apparently started a forest fire. They had to call forestry to put it out,” Rick said.

The soldiers made such an impression on the general he asked why there aren’t more people of Chinese descent in the Army.

"They took him aside and said 'well, don’t you know Chinese aren’t allowed because of discrimination?'” Rick said.

Rick said the general began making phone calls as a result.

“The camp played a central role in changing race relations,” Rick says.

The commandos also proved their training prowess on the coast by planting magnets to imitate mines on ships moored near Powell River, and 'tagging' defensive guns along the coast without permission from higher levels of command.

“This was pretty dangerous stuff. It was wartime, these guys could have been killed,” Rick said.

He said his father had a box of detonators stored in the basement of their Ontario home for years. One day Hank explained the various explosives and how they worked to young Rick.

“He took them to the local police station shortly after that. I guess he was afraid I might get into them,” Rick said.

Former Chinese Canadian soldiers and dignitaries pose for a photo while dedicating Commando Bay on Okanagan Lake in September, 1988.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Rick Wong

Hank returned to Commando Bay on Sept. 17, 1988 as part of a commando reunion and plaque dedication.

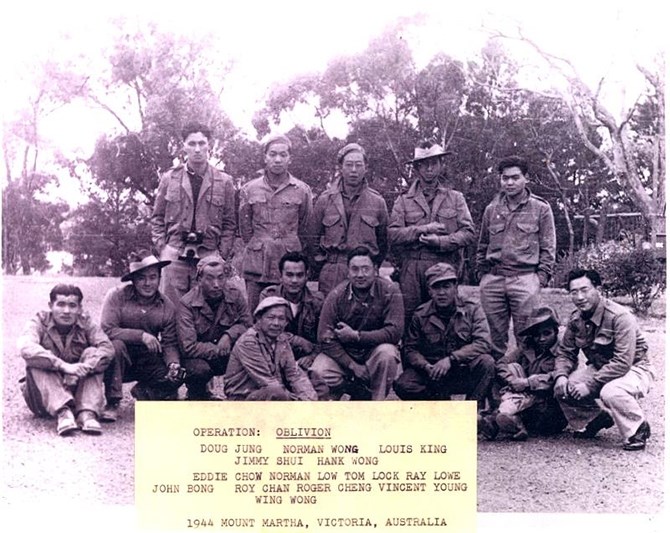

Along with Hank were twelve other Chinese Canadians who were recruited for the mission. They were sent to Commando Bay (then known as Dunrobin's Bay, although the commandos knew it as Goose Bay) to participate in a four-month training session where they lived in tents, learned to roll out of moving vehicles, hand-to-hand combat, radio telegraphy, demolition, sabotage, gun maneuvers using live ammunition and self preservation techniques.

The members of 1944's "Operation Oblivion." Hank Wong is at back row, far right.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Rick Wong

The initial mission of Operation Oblivion was to drop the commandos into Japanese occupied China, to seek out resistance fighters and help arm and train them in sabotage and espionage.

They were considered spies, which meant if caught they would likely be executed.

It was, in many ways, a suicide mission.

The men were then shipped to Melbourne, Australia, where they were subject to more commando training. Wong learned to parachute, among other things, and was preparing for activation when the war suddenly ended and the mission canceled.

The men were left high and dry in Australia, with no way to get home, Wong said in a Veterans Affairs Canada interview.

“We were told to go home, but there was no way to do that,” he said, as the American forces in the Pacific had tied up most means of transportation.

Wong ended up working his way back to Canada on tramp steamers, eventually sailing into Vancouver on the Kitsilano Park, a 25-tonne freighter.

Wong’s commando unit was sworn to secrecy for 25 years. Few details of the operation were known until the documentary Operation Oblivion was released around six years ago.

Photographs taken by Wong with a smuggled camera also survived.

Locally, there is very little left to remind anyone of the top secret training camp on the east shore of Okanagan Lake today. The camp was torn down and a wharf removed along with any other sign of military activity. All that is visible today is the plaque explaining how the name came to be and a list of members of the operation.

A memorial plaque and some signage is all that remains of Operation Oblivion's training gounds at Commando Bay on Okanagan Lake today.

Image Credit: Marshall Jones

To contact a reporter for this story, email Steve Arstad or call 250-488-3065 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to tips@infonews.ca and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2019