The Coquihalla Highway as it approaches the Coquihalla summit. Construction of the highway in the late 1980s unlocked the door to economic growth in Kamloops, and especially Kelowna.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Wikimedia Commons

December 12, 2021 - 12:02 PM

— This story was originally published April 3, 2021.

If you're a regular motorist on the Coquihalla Highway, you probably love it for the high quality engineering of the road that allows you to cruise at modern highway speeds, unencumbered by traffic, to and from the Lower Mainland to the Okanagan or Kamloops.

But you probably have other thoughts during the winter, when metres of snow and ice pile up on the Coquihalla summit, making the roadway below a dangerous and difficult drive.

Actually that can and often does happen virtually any month of the year on the Coquihalla.

British Columbia’s Coquihalla Highway has been a blessing and a curse since the first phase opened in May, 1986, just in time for Expo 86 in Vancouver.

Since then, the four lane superhighway has reduced travel time to the coast to four hours for cities like Kamloops and Kelowna, accelerating the growth of those cities and the interior of the province.

But that time saving connection can come at a cost in terms of reliability, and sometimes lives, as the highway is carved through some of the most challenging terrain and environment in the southern half of the province.

That fact has made the highway a drivers’ challenge for probably the majority of months in a year, as Pacific weather systems can dump snow on the highway’s summit almost every month of the year, not to mention the metres of snow falling on the highway in a traditional winter.

Taking a closer look at the highway’s history, we find the travellers' struggle to get through the Coquihalla canyon has always been this way.

History

Historically, the Coquihalla Pass has been the bane of those passing through the interior since its first use by Europeans as a trade corridor by the Hudson's Bay fur brigades in 1848.

In his book, “The Coast Connection” R.G. Harvey provided a description of the early Coquihalla trails by Royal Engineer Lieutenant Palmer (Harvey was a professional engineer who served as B.C’s deputy minister of highways from 1976 until his retirement in 1983.):

"It is difficult to find language to express in adequate terms the utter vileness of the trails… dreaded alike by all classes of travellers… slippery, precipitous ascents and descents, fallen logs, overhanging branches, roots, rocks, stumps, turbid pools and miles of deep mud…”

Sappers (British colonial soldier-engineers) tried to create a trail up the Coquihalla in 1859-60 but snowfall and the avalanche threat was too much.

They soon realized one could only use the Coquihalla Pass at best for five months of the year.

The canyon’s conditions were well known by the time Canadian Pacific began building the Kettle Valley Railway through the Coquihalla canyon in 1915.

Barrie Sandford recalled in "McCulloch’s Wonder,” a story about the Kettle Valley Railway’s first taste of the Coquihalla: “The snow was so deep in Dec. 1915 during construction of the rail line, a rotary plow train got stuck in heavy snowfall in the pass and had to be abandoned until spring, a harbinger of many tough winters ahead for that part of the rail line."

The railway eventually abandoned the Coquihalla portion of the line in 1962 after years of washouts, landslides and winter closures due to heavy snow.

R.G. Harvey described the first political discourse regarding construction of the modern Coquihalla Highway as being discussed in a British Columbia throne speech in 1977 in which it was noted a new route to the coast from the interior was needed.

At that time, the Hope-Princeton Highway was 28 years old. A proposal to build 70 miles of new highway from Hope to Merritt was made.

READ MORE: "70 years ago the Hope-Princeton Highway opened, forever changing the Okanagan."

The Trans Canada Highway 1 through the Fraser Canyon was reaching its capacity in terms of traffic, and neither the Fraser Canyon nor Highway 3 offered as direct a route through the province as the proposed Coquihalla route did.

Improving either of the other two alternatives would have been prohibitively expensive, and environmentally dangerous in the narrow and crowded Fraser canyon.

Not much happened until 1984 when the idea of pairing the opening of the highway to Expo 86 became politically popular.

Then premier of the province and resident of Kelowna, Bill Bennett was, probably unsurprisingly, a major proponent of the new highway.

Construction of the 120-kilometre section from Hope to Merritt began in the fall of 1984 and opened in May, 1986.

It was actually a remarkable achievement – construction of a four-lane freeway with 3.7 metre paved lanes, truck lanes on extended up and downgrades, a 2.4-metre-wide grassed centre median or concrete barriers, 1.6 metre wide paved safety shoulders and guardrails where necessary.

Harvey called the highway "one of the finest highways ever built over a major mountain range."

Phase 2, Merritt to Kamloops was completed in September, 1987 and the Okanagan Connector opened in October, 1990.

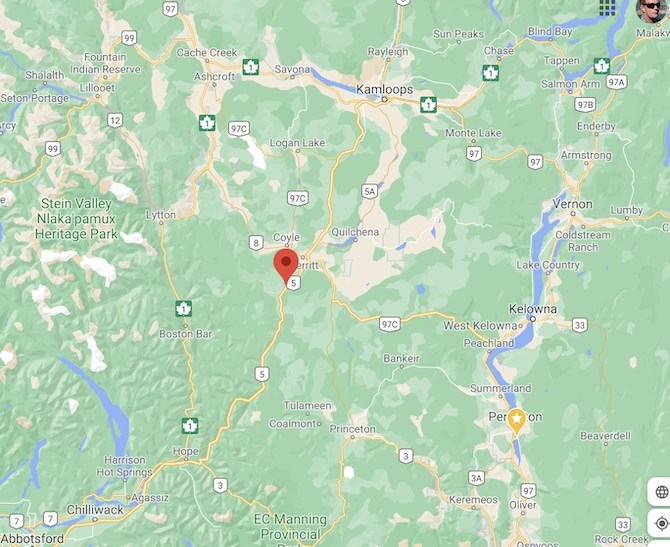

A map showing the Coquihalla Highway from Hope to Kamloops, and the Okanagan connector from Hope to Kelowna. (Highway 97 C)

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Google maps

Economic gains and population growth

Ken Denike, UBC Department of Geography PhD assistant Professor Emeritus is an expert in transportation issues.

Denike looked at population figures between 1981 and 2020 for the Kamloops and the Okanagan’s largest centres.

Perhaps surprisingly, Kamloops only grew from 64,048 to 67,055 in the decade between 1981 and 1991, during which time the Hope to Kamloops section of the Coquihalla was constructed.

But in the following 10-year period, the city grew from 67,055 in 1991 to 80,457 in 2002.

Merritt also appears to have benefited greatly from the highway. In the decade between 1986 and 1996, the once-sleepy interior town's population grew from 6,189 to 7,631, up 22.1 per cent.

The opening of the Coquihalla connector in 1991 appears to have had a much bigger impact on Kelowna, which saw its population grow from 59,196 in 1981 to 75,950 by 1991.

Between 1991 and 2002, however, growth in Kelowna vastly outpaced any other Okanagan community, going from 75,950 in 1991 to 102,384 in 2002, nearly 27,000 residents, a number almost equal to the size of Penticton at the time.

During the same period, Kamloops added about 13,000 residents, Vernon around 12,000 and Penticton around 5,000.

Denike compared the growth in ‘functions’ – defined as separate services available in a municipality, (i.e. one establishment might have several services such as a gas station with a convenience store and/or food services.)

"With respect to the centres most changed as a result of the Coquihalla highway, the telling number is the number of functions in 1981, pre-construction, and functions in 2020. It’s in the difference between these numbers,” Denike says.

Comparing functions of various municipalities most likely to be affected by the Coquihalla Highway, Denike found Kelowna more than doubled that number between 1981 to 2020, from 1,865 to 3,763, an increase of 1,958.

Kamloops, Penticton and Vernon didn’t come anywhere close to matching that increase.

There is no early data for West Kelowna, which wasn’t incorporated in 1981, but in 2020 the city had 1,959 functions, more than Penticton and Vernon.

In his analysis, Denike used the District of Summerland as a base measurement to compare growth in other centres against.

The ranking of the centres in 1981 was:

-

Kamloops

-

Kelowna

-

Penticton

-

Vernon

-

Summerland

“The Coquihalla changed the network and altered accessibility significantly,” Denike says.

By 2020, the ranking was:

-

Kelowna

-

Kamloops

-

Vernon

-

Penticton

-

Summerland

Denike says another interesting change to the Central Okanagan economy was the rise of West Kelowna as a major urban hub.

Okanagan historian Don Knox says the highway reduced driving time between the Lower Mainland and places like Kelowna and Kamloops by one and half to two hours. What used to be a five and a half to six hour trip could now be done in four.

"One thing you did see was a new interest in recreational property. Sales around Big White began to take on greater importance as the reduced driving time made the Kelowna ski resort attractive as a weekend retreat for Lower Mainlanders who were priced out of Whistler. You couldn’t do Kelowna as a day trip for skiing, but it became doable where you could drive up and ski Saturday and Sunday, and drive back Sunday evening.”

Kelowna historian Bob Hayes says the Okanagan connector was a logical progression from the Hope-Princeton Highway, which opened in 1949.

"Up until then, Kelowna was pretty isolated, in fact the whole Okanagan was isolated. The next step was the 1958 opening of the bridge, which linked Kelowna with the West side, then I think the connector was the final piece of the puzzle in terms of making it easier to get to the coast," he says.

The Okanagan cities of Vernon, Kelowna and Penticton were all roughly the same size up to a few decades ago. Hayes believes the connector has diverted a lot of through traffic into Kelowna, making the coast more accessible. A drive that took all weekend now can be done in a day.

"Opening of the connector is also when property prices really started to rise. People on the coast realized they could buy property here and make a weekend trip out of a visit to the Okanagan. I don’t think there is any doubt it has had a huge impact. I don't think you can isolate the connector - it's part of a series of changes, but arguably the most important one," Hayes says.

In Kamloops, one of the biggest changes the city has seen is its rising status as a major hub in the province's most important highway corridor linking the Lower Mainland and the Alberta border.

Venture Kamloops' Jim Anderson says truck traffic has seen a significant boost through the city since the highway was completed.

He says an as yet unreleased report found fully 60 per cent of all truck traffic heading to the Lower Mainland in British Columbia now uses the Coquihalla Highway

“I just got this report the day before yesterday, and I didn’t expect that,” Anderson says.

Thompson Nicola Regional District Board Chair Kenneth Gillis believes the opening of the Coquihalla has had a profound effect on the whole region, not just the City of Kamloops.

He's lived in Kamloops since 1963, and is a former trucker and frequent user of the Coquihalla Highway today.

"From my observations, the highway clearly attracted the attention of major retailers. They might have located here anyway, but opening of the highway hastened that. Expansion in Kamloops has been monumental since 89-90," he says.

Gillis notes before the highway, Kamloops' only connection with the coast was through the Fraser Canyon on the Trans-Canada.

"The change in truck traffic in the last 10 years has been astronomical. I drive the Coquihalla frequently now living in Merritt. I take the Merritt to Kamloops portion two or three times a week, and the number of trucks is unbelievable. I never considered Fraser Canyon highway to be inadequate, but if we had to put today’s truck traffic through the Fraser Canyon today, it would be a nightmare," he says.

Gillis says truck traffic feeds the commerce of Kamloops. The highway also contributed in large measure to expansion of industry in and around Kamloops, creating new opportunities to bring in raw materials and ship out the finished product.

Coquihalla Highway Fast Facts

-

A toll booth set up to pay for the highway’s construction costs was removed in Sept. 2008. Tolls included a $5 charge for motorcycles, $10 for cars and up to $50 for trucks. The booth was located 13 km north of the snow shed.

-

The highway is 543.3 kilometres in length

-

The Coquihalla summit is 1244 metres, or 4081 feet. It's the 11th highest highway pass in B.C., and the second highest four lane, divided highway pass.

-

The Coquihalla has been labelled one of the worst roads in winter in all of North America. It spawned a popular TV series in 2012 called “Highway Thru Hell." The series documents the operations of a Hope towing company dispatched to collisions on the highway.

-

In a comparison of two major highway connections from the coast to the interior, the figures for rock and soil moved during construction of the highway is impressive. Construction of the Hope-Princeton highway in 1949 involved moving 3.76 million cubic metres, compared to 27.5 million cubic metres moved during the Coquihalla construction.

A scene from this past winter on the Coquihalla Highway. The Hope to Merritt section of the highway is particularly notorious for incredible winter snowfalls.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED /Tran BC

Environment and road conditions

The reason the Okanagan and Kamloops are so dry is the same reason the Coquihalla is so wet.

It’s called the rain shadow effect, caused when a Pacific frontal system dumps most of its moisture on B.C.'s Cascade mountains.

As often as not, the forecast for snow on the Hope to Merritt section can be 10 times what Kelowna or Kamloops might get.

READ MORE: "The weather phenomenon that makes our Kamloops, Okanagan paradise"

The Dry Gulch area on the highway’s Hope to Merritt section is the climatic dividing line in the valley between interior plateau and coastal weather, sort of an ‘environmental divide.’

From Dry Gulch south to Hope is probably the snowiest section of the Coquihalla.

Historical data from the Coldwater maintenance yard weather station (7.5 km north of the highway summit) had average annual snowfall almost exactly 50 per cent of the Coquihalla summit weather station, and snowfall continues to taper off north towards Merritt. The highways ministry says the Larson Hill weather station gets only 33 per cent of the annual snowfall of the summit.

The average annual snowfall is 994 cm at the Coquihalla summit weather station, according to the Ministry of Transport. The maximum snowpack depth is 225 cm. This year’s snowfall to Feb. 28 was 872cm, 120 per cent of the average for that date.

B.C.’s Highways ministry admits the Coquihalla experiences some of the most extreme winter storms in the province and the heavy, wet coastal storms make for "very challenging conditions."

The ministry has brought in tougher standards for maintenance contractors that include being more proactive. They say serious and fatal winter collisions on the corridor are down an average of 23.5 per cent over the past three years.

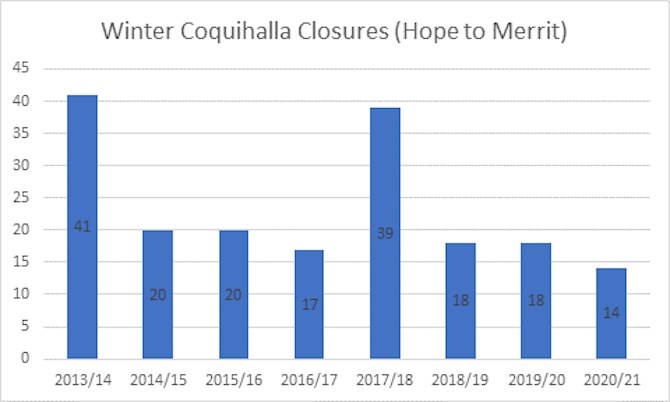

Nonetheless, between Oct. 30, 2017 to April 30, 2018 there were 27 closures on the Coquihalla between Hope and Merritt.

From Oct. 30, 2019 to April 30, 2020 there were 11 closures on that section of highway, and so far this year there have been 15 closures of the highway, one for avalanche control.

Based on past history, it would seem the writing was on the wall. Since authorities began planning the highway, it has always been a given that weather and environment would result in operating challenges.

What may be a bit surprising to some is that even with today’s level of technology, the highway can still be impassable at times.

The Coquihalla Highway from Hope to Merritt covers three road maintenance contract areas. There are approximately 219 pieces of winter equipment available in these three areas, but not all are allocated to the Coquihalla. It remains up to the contractor to develop resource plans to clear the highway following a heavy snowfall.

“Aside from major avalanche cycles that can close the highway for days at a time, snowfall events exceeding 10 cm per hour for several consecutive hours will also result in closures of several hours or longer duration. These closures are done for the safety of the people who are travelling on these mountain passes,” the ministry said in an email.

When it comes to weather, not much has changed since the days of the fur brigades in the Coquihalla canyon.

The Coquihalla Highway passes through some of southern B.C.'s most formidable terrain.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED /Tran BC

A graph showing the number of times over the past 8 winters the Coquihalla Highway has closed. From a historical point of view, not much has changed.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED / Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure

— This story was corrected at 10:43 a.m. Friday, April 9, 2021 correct the elevation of Coquihalla summit.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Steve Arstad or call 250-488-3065 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to tips@infonews.ca and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2021