Penticton Museum Curator Dennis Ooman studies a sword believed to be Sri Lankan in origin, possibly evidence of an unrecorded Spanish incursion into the Okanagan and Similkameen valleys in the mid 1700s.

(STEVE ARSTAD / iNFOnews.ca)

April 23, 2016 - 11:30 AM

THOMPSON-OKANAGAN - If your history books tell you fur traders were first to make contact with First Nations in the B.C. Interior, soon you may replace those pages with new evidence of Spanish Conquistadors who may have made a brief, though adventurous, stay in the Okanagan and Similkameen Valleys.

While there appears to be evidence and artifacts of a Spanish incursion into what is now British Columbia, how the Conquistadors got here and what happened some 70 years before the first fur traders arrived, continues to engage historians and residents as they look for a ‘smoking gun’ of solid proof.

In the 1978 version of his book Similkameen: The Pictograph Country, late Similkameen politician and historian Bill Barlee tells of a heavily-armed Spanish expedition entering the Similkameen Valley around the mid-1700s and setting up camp near the site of the present day Village of Keremeos.

His version of events tells of an altercation between an Indian from the Similkameen valley and a Spanish soldier resulting in a no-contest battle between the indigenous population and the heavily armed Spanish, who apparently were professional soldiers.

The Spanish took several native prisoners and retreated up the valley of Keremeos Creek, crossing the divide to Shingle Creek and eventually making their way to the eastern side of Okanagan Lake, where they followed an ancient native trail north up the lake, Barlee says in his book. The Spanish eventually set up camp in the Kelowna area where they wintered until the following spring.

Barlee suggests the group may have been stricken by disease, or had further encounters with natives over the winter, and their numbers were considerably reduced when the Indians from the Similkameen met them again on a small flat overlooking Keremeos Creek.

As Barlee tells it, the Similkameen natives learned of their approach and lay in wait, attacking the Spaniards somewhere between Keremeos and Olalla, where they were ultimately decimated by the natives.

"It is said the Spanish were then buried along with their weapons and armour, in a low grassy mound somewhere between the last Spanish camping place and the Indian village known then as Keremye’us,” Barlee concludes in his tale.

Local historian Bill Barlee's tale of a Spanish incursion is outlined in the 'Similkameen: The Pictograph Country'.

(STEVE ARSTAD / iNFOnews.ca)

BARLEE: THE EVIDENCE

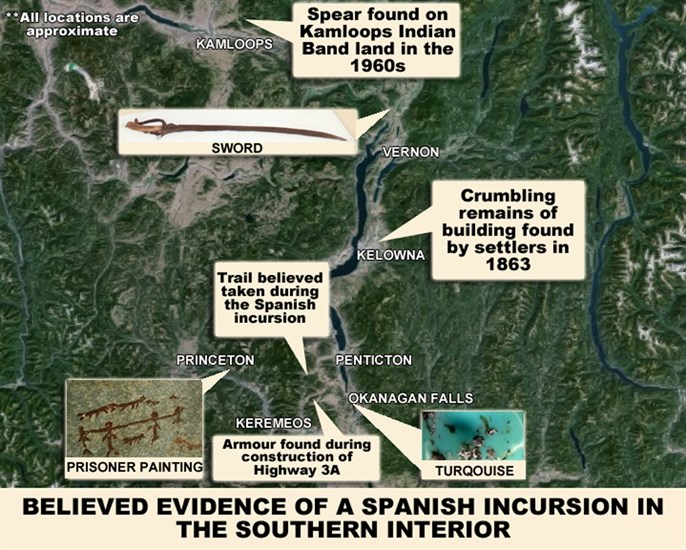

In his book, Barlee notes local evidence discovered over the years which appeared to corroborate the story, including old steel weapons found throughout the valley, some of which were located close to Keremeos.

Although possibly trade items, it seems unusual there would be so many concentrated around Keremeos, he notes.

Also tucked away in the Similkameen Valley are the famous ‘Prisoner Paintings:’ native pictographs, including one which appears to depict four Indians chained together and surrounded by what appear to be guard dogs.

Barlee also describes rare Indian armour, including hammered copper plate, found in an old burial site near Keremeos.

He further notes the discovery of a highly polished piece of turquoise found in an Indian burial in Okanagan Falls during the early part of the 20th century. Barlee claims it was the ‘only documented instance of turquoise being found in an Indian grave in the province’ leading him to ponder whether the stone could have possibly come from one of the Spanish soldiers.

Also seen as possible evidence was the discovery by Kelowna settlers, in 1863, of crumbling remains of a large building, estimated to be 35 feet by 75 feet in size, with one account attributing the location to roughly where Orchard Park Mall is today.

Artifacts and stories from around the region lend to beliefs Spanish Conquistadors could have travelled through the B.C. Interior.

Image Credit: iNFOnews.ca

DIFFICULT TO VERIFY

Penticton Museum Curator Dennis Oomen believes the story of a lost Spanish party in the region could very well have a basis in reality.

“It is possible. However, the whole story raises some problems in historical terms that make it very difficult to verify,” he says.

From all accounts he’s heard of the story, it speaks of a sizeable number of Spaniards, which implies this wasn’t a lost group of shipwrecked sailors wandering around the interior of Washington State and southern B.C..

“It’s possible they came from a shipwreck, as one theory postulates, but assuming it was a large group, well-organized and well-supplied, that would imply it was an official Spanish expedition into the interior. That would have come under the aegis of the Spanish Crown and the Spanish Colonial authorities, and it would have been well-documented,” he says.

Oomen also notes the Spaniards had a functioning bureaucracy which excursions and expeditions.

"The other thing is interpretation — natives called them the turtle people in reference to front and back armour and presumably helmets. One historian has said once the Spaniards got around to exploring North America, they were no longer wearing this heavy armour,” he says, noting he feels the description ‘turtle people’ is a modern term which has slipped into the story.

Oomen says no official account has ever turned up describing a Spanish expedition this far north, but says the group of men could have possibly been on a clandestine mission which never made it into official record books. Or, he says, the group passing through the valleys could have been part of a privately sponsored exploration by wealthy Spaniards and colonial authorities without the knowledge of the Spanish Crown or the bureaucracy.

A depiction of the armour a Spanish conquistador would wear.

Image Credit: CarlosVdeHabsburgo via Wikimedia Commons

WEAPONS AND ARMOUR

Oomen counts a sword in the possession of the Penticton Museum among corroborating physical evidence found over the years.

“The sword is of Sinhalese, or Sri Lankan origin. It could have been brought over by the Spanish, but it may also have been a presentation sword given to local native chiefs by early fur traders to the valley,” Oomen says.

"As a former curator of Kamloops Museum, I was going through their collection and came across a spearhead of a specific type, I would call it a spontoon, a short spear carried by an officer from the 1600s to the early 1800s. It was found on Kamloops Indian Band territory in the 1960s,” Oomen says.

He calls it a ‘tenuous connection’ but adds it’s what it looked to him.

"Were they traded? It doesn’t seem likely, but it is unusual, not what you’d expect to find,” he says.

Anecdotal evidence about the Spanish incursion also comes from local stories.

In 2013, Keremeos resident Betty Borke recalled a story related by family friend Joe Detjen, who worked on the construction of Highway 3A in the late 1940s.

The route from Keremeos to Highway 97 via the Yellow Lake pass was barely more than a wagon road prior to this construction work. Detjen recalled one of his fellow workers turning up what was described as a Spanish shield somewhere near the first stage of the long climb out of the Similkameen Valley, on Highway 3A north of Stagecoach Road, when heavy equipment began working on the road in 1948.

Native pictographs in the Simlikameen area include the 'Prisoner Paintings,' which appears to depict four Indians chained together surrounded by what look to be representations of guard dogs.

Image Credit: Stanley Copp

THE PRISONER PAINTINGS AND BURIAL SITES

Stanley Copp, chair of the Sociology and Anthropology Department at Langara College in Vancouver, has performed archeological digs in the area and often spoke with Barlee about the likelihood of Conquistadors in the B.C. Interior. He was part of an archeological excavation several years ago at the site of the ‘Prisoner Painting’ pictograph, which is located in the Similkameen Valley.

“The site is kind of a sacred place, like a church. It’s been in use for 4,000 years. I was hoping to find some evidence of a Spanish visit, but there wasn’t anything there of a historic nature,” Copp says.

Copp has located an area where he believes the Spanish burial site may be — a location where he has detected a low mound which doesn’t look like it was created naturally. He’d like to have the time and money to survey it using ground penetrating radar, a technique which could reveal the burial site without having to dig it up.

Copps is also intrigued by the Sri Lankan sword in the Penticton Museum. No one knows much about the sword’s history, only that it was found in the North Okanagan.

He’d like to find a known original to compare it to, noting it could have had its origins as a ceremonial present to a local native chief, as an officer’s ceremonial trappings, or it could be a replica.

Copps is also trying to get a grant from the Canadian Geographical Society to look into museum archives in order to glean more information about at least two other edged weapons found in the Okanagan.

“They might be Spanish, but the question is, from where and when did they come?” he asks. “What we need to find are a few more artifacts, particularly in First Nations sites.”

CHALLENGING THE EVIDENCE

A paper published by the Royal Museum of B.C. called The Chuchawaytha Rock Shelter Pictographs by Grant Keddie in 2005 explains the ‘Prisoner Painting’ in somewhat different terms.

Keddie concludes the story of the Spanish incursion is clearly not of First Nation origin and instead is interpreted by early settlers as depicting Spaniards taking native hostages; Indigenous people have not endorsed it.

“Although there is a First Nations story about some Euro-Americans being killed in the 19th century, the interpretation that the story is earlier and applies to the Spaniards is a non-First Nation development,” Keddie writes.

After examining it in the Princeton Museum in 1981, he says a piece of Spanish armour found in the region is actually a small piece of an early 20th century Chinese brass table with parts of engraved dragon motifs.

Keddie also believes he has identified the individual who painted the prisoner images as Francois Tomoican (Tomar), who painted the images while on a spirit quest in 1871 when he was 14 years old. Keddie says Tomoican did not give any meaning to the glyphs other than to say he painted the scene.

EDITORS NOTE: Attempts to find an interpretation from the Okanagan Nation Alliance were unsuccessful.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Steve Arstad or call 250-488-3065 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2016