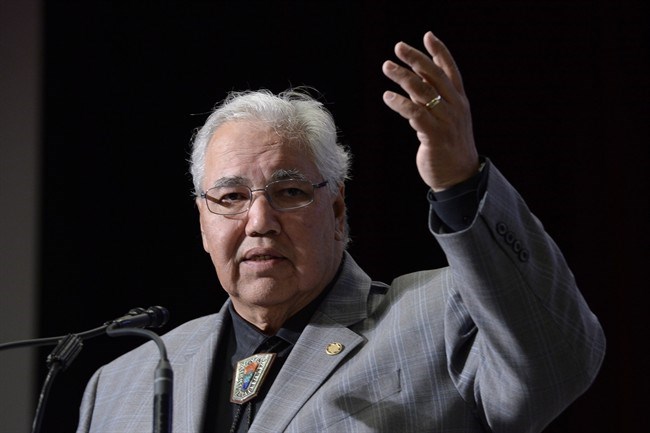

Commission chairman Justice Murray Sinclair raises his arm asking residebtial school survivors to stand at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Ottawa on Tuesday, June 2, 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Republished June 02, 2015 - 4:38 PM

Original Publication Date June 02, 2015 - 1:00 AM

OTTAWA - A moment of shared emotional catharsis bound survivors of Canada's residential schools Tuesday as their collective ordeal was officially branded a "cultural genocide" that tore apart their families and left them to contend with lifelong scars of physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

The massive report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission makes 94 broad recommendations —everything from greater police independence and reducing the number of aboriginal children in foster care to restrictions on the use of conditional and mandatory minimum sentences.

But with the extent of the abuse endured by survivors now fully documented, with plans for a permanent centre at the University of Manitoba to open later this year, the political road to reconciliation remains far from smooth.

The report summary — the full six-volume collection isn't due out until later this year — is the culmination of six emotional years of extensive study into the church-run, government-funded institutions, which operated for more than 120 years.

"Our spirit cannot be broken," commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild, himself a survivor of residential school, told a packed meeting room at a downtown Ottawa hotel.

"We have listened very carefully to many courageous individuals in our search for truth ... through pain, tears, joy and sometimes anger, you shared with us what happened.

"There are still many, many survivors who have not healed enough to come forward with their story, or that are too angry to tell their story — or worse, there are those who have given up hope."

The personal stories documented by the commission included a heart-wrenching account of sexual abuse from Josephine Sutherland, who attended the Fort Albany residential school in Ontario.

"I couldn't call for help, I couldn't," Sutherland told the commission.

"And he did awful things to me, and I was just a little girl ... I was so stunned, I couldn't move, I couldn't."

Justice Murray Sinclair, the commission's chairman, said the experiences of 6,750 survivors who spoke to the commission will be housed at the University of Manitoba as a "permanent historical archive, never to be forgotten or ignored."

"The residential school experience is clearly one of the darkest most troubling chapters in our collective history," Sinclair told the hundreds who gathered to mark the release of the commission's findings.

"The survivors showed great courage, great conviction and trust to us in sharing their stories," he said. "These were heart-breaking, tragic and shocking accounts of discrimination, deprivation and all manner of physical, sexual, emotional and mental abuse."

Sinclair also stressed the need for Canadians to know the horrific history of residential schools. The federal government estimates around 150,000 students attended the institutions. The last school, located outside of Regina, closed in 1996.

"The survivors need to know before they leave this earth that people understand what happened and what the schools did to them," he said.

"The survivors need to know that having been heard and understood that we will act to ensure the repair of damages is done."

The recommendations of the commission, borne out of the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history, touch on a host of problems plaguing Aboriginal Peoples, including child welfare, education, justice and health.

They include a call for a national public inquiry into missing and murdered aboriginal women, a request for the Pope to apologize for the Roman Catholic's role in the residential school system and for Canada to full adopt and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

During a question period dominated by the commission's findings, NDP leader Tom Mulcair asked Prime Minister Stephen Harper if he would accept the recommendation on the UN declaration.

Harper was non-committal, especially when Mulcair asked him to acknowledge the commission's use of the term "cultural genocide." Harper steadfastly avoided repeating the words.

"The government accepted the UN declaration as an aspirational document," Harper said.

"We have taken specific actions, Mr. Speaker, to enhance the rights of aboriginal people, particularly women living on reserves, and generally all aboriginal people under the Canadian Human Rights Act."

Harper said his government would review the recommendations, but did not commit to specific action. Both the Liberals and the NDP said they would act on the recommendations, but offered few other details.

Sinclair and Harper also met privately Tuesday to discuss the commission's findings, which included an estimate that more than 6,000 children died during their time at residential school.

The two shared a "frank and open dialogue," Sinclair said in a statement.

"He was open to listening to some of our concerns and inquired about some of our recommendations. I remain concerned with the government's resistance to the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples."

Sinclair said the commission has offered to meet with the prime minister again after he has reviewed the findings. "We look forward to continuing the conversation."

NDP MP Romeo Saganash, the party's deputy aboriginal affairs critic, described how he witnessed abuse first-hand.

Saganash, who helped to draft the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, was removed from his home at the age of six to attend a residential school in Quebec.

"This report and this commission has allowed me to close that chapter of my life," he said.

In its summary, the commission said the TRC's work is designed not to close a "sad chapter of Canada's past" but to open "new healing pathways."

"We are mindful that knowing the truth about what happened in residential schools in and of itself does not necessarily lead to reconciliation," the summary said. "Yet, the importance of truth-telling in its own right should not be underestimated."

Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt, who was among those speaking at a news conference after the report's release, described the pain he witnessed from survivors who shared their experience.

"It is with great sadness that I heard that many who were abused and bullied have carried a burden of shame and anger for their entire lives," Valcourt said.

"I want to send to all of those people a message ... those who should feel shame are not the victims, but the perpetrators."

News from © The Canadian Press, 2015