Paige was only 19 years old when she died in Vancouver's notorious downtown eastside

Image Credit: contributed

May 29, 2015 - 4:31 PM

KAMLOOPS - In a lengthy report documenting the plight of a young aboriginal girl failed by several bureaucracies, a critic says apathy, incomplete reports and inaction from ministry workers were significant contributors to a Kamloops girl's continual homelessness and eventual death at 19 years of age in the squalor of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Representative for Children and Youth Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafonde submitted her 50-page report “Paige’s Story: Abuse, Indifference and a Young Life Discarded,” to the legislative assembly of B.C. earlier this month and hopes staff working in several ministry agencies will use it to change approaches towards children, particularly aboriginal children, navigating the system designed to protect them.

“Paige’s story reveals the massive gap between our understanding of the effects of trauma and the systems at the front line — the social workers, police, school staff and health care providers. Professional standards of care were not upheld in how Paige was treated,” the report says. "This raises intense concerns about the professional judgment of those in the system. Her suffering is detailed in this report and it will sicken every reader to know that this happened in Vancouver, under the watchful lens of a social services system that should have done better."

To develop the report, Turpel-Lafonde collected 30 child protection reports alleging neglect, domestic violence, and abandonment of a girl referred only as Paige — a regular in the Ministry of Children and Family Development’s system. Through interviews with Paige’s relatives, foster caretakers and ministry staff who handled her file, the representative gained a snapshot of the child’s life under the reliance of social funding and a mother with drug dependencies.

Paige was born to a 16-year-old mother in Kamloops. Because of the mother's transient lifestyle, drug and alcohol use and domestic violence, the ministry stepped in three different times to remove Paige who ultimately stayed with her mother. Ministry workers did not conduct an assessment of the mother to determine if she was capable of parenting — a trend that would continue throughout Paige’s life.

When Paige began daycare, reports stated she arrived with poor hygiene and would act out "in a sexualized manner" with her cohorts. By the time she was seven years old, the ministry received a report her mother was using crack cocaine and there was no food in the home. She was removed and placed in a home with her grandmother but was later molested by the caretaker’s boyfriend. Paige returned to live with her mother where further reports were filed on her mother’s drug use.

The pattern continued as mother and child moved from several locations in B.C. Between the ages of three to 13, Paige moved from her mother’s care, to family placements and foster homes between Fort St. John, Kamloops and other locations a total of 15 times.

Ministry workers often returned Paige to her mother’s care with promises she no longer used crack cocaine. Workers never requested a drug test from the mother whose drug use continued until staff removed Paige again. The girl was placed with a foster family whom she created a bond with. Paige's life stabilized somewhat until her mother discovered where she lived.

“The mother located the home and began to keep a constant watch on the property. She sat on a park bench facing the foster home and spent hours each day watching (it),” the report says.

After the mother’s behaviour turned threatening, authorities removed Paige from the home.

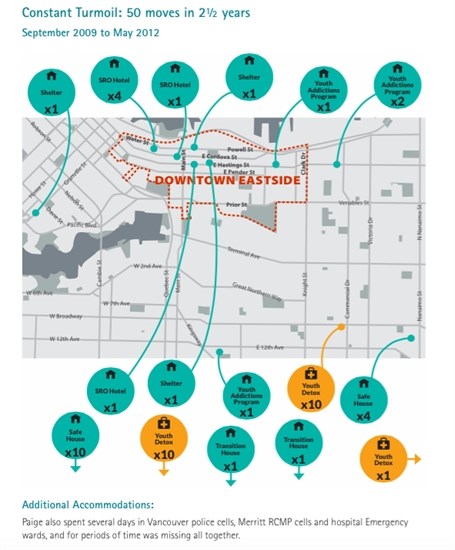

At 16, Paige and her mother moved to Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. At that point, the total amount of moves her mother made was around 84. Paige would go on to move an additional 50 times before her death at 19.

A social worker documented a meeting with Paige who said she was tired of moving all over the province and wanted to go back to school. She was concerned about her mother’s drug use and said she was thinking of suicide.

After registering in school, a counsellor looked at Paige’s file and questioned why no legal action was taken on the Ministry’s part to protect the girl. At this point, Paige became dependent on drugs and alcohol.

"The file is unbelievable," the counsellor said. "The amount of times she was sent home, doing drugs at about grade five, smoking pot. A couple of times she’s come into school late and when we talked with her, she said mom’s boyfriend had been arrested at the apartment or mom had been (arrested). You know there was just turmoil after turmoil."

Paige regularly went to search for her mother who drifted from shelters to churches to the streets. In one instance, a ministry worker connected with Paige’s mother on the phone. The mother claimed she was looking for housing with her daughter and was no longer using crack cocaine. Paige was not interviewed and the mother was not asked for a drug test. The ministry closed the file.

In other files, workers would note Paige was unwilling to accept ministry services or leave her mother. The pair went on to become homeless for five months after the mother’s violent behaviour prevented them from entering shelters.

At one point, Paige’s aunt and uncle offered to take her into care, but the ministry refused the arrangement. The family members ended up looking after the girl’s cats while she lived in single-room units on skid-row.

Paige left high school and her reliance on alcohol increased. She began to exchage sex for alcohol. She was named in over 40 police files and ended three pregnancies.

As her downward spiral continued, social support became sparse as she was incapable of making decisions on her own. Workers continued noting on her file about her lack of progress, not keeping appointments or her mother’s refusal for service.

“The Representative is troubled by the fact many professionals and others involved on the front lines seem to regard poor outcomes for Aboriginal children and youth as inevitable, justifying this by blaming these children for being ‘service-resistant’ or inappropriately placing the onus on the child or youth to seek help when they are already traumatized, abused and effectively abandoned to fend for themselves on the street,” the report says.

Social workers who would go out searching for Paige wouldn’t enter some of the units where the child lived out of personal “safety concerns."

“The Representative finds it appalling that workers would be reluctant to enter certain hotels because of well-founded concerns about their personal safety while having the knowledge Paige was living there."

Paige moved into one final foster home prior to her nineteenth birthday. On that day she would be considered an adult and no longer eligible for protective services. Despite the foster parent’s offer to continue parenting past Paige’s birthday, the ministry decided Paige would move to an apartment.

“No ministry social worker visited to check the appropriateness of this living situation and her file was closed,” the report said. “On the day Paige was to move… the foster parent packed up all of her belongings in garbage bags and left them at Paige’s school."

About a month later, Paige’s drug use escalated. She began using methamphetamine and died of a drug overdose in a public washroom near Oppenheimer Park in the Downtown Eastside. Her mother died 18-months later.

“The child protection system failed utterly to prepare Paige for adulthood and her brief experiences of adulthood was self-destructive and fully predictable. The transition process was not a process — it was a passing of responsibility and an indifference to her circumstances,” Turpel-Lafonde said.

To read the report and Turpel-Lafonde's recommendations, click here.

All of Paige's moves in a span of three years

Image Credit: contributed

To contact a reporter for this story, email Glynn Brothen at gbrothen@infonews.ca, or call 250-319-7494. To contact the editor, email mjones@infonews.ca or call 250-718-2724.

News from © iNFOnews, 2015