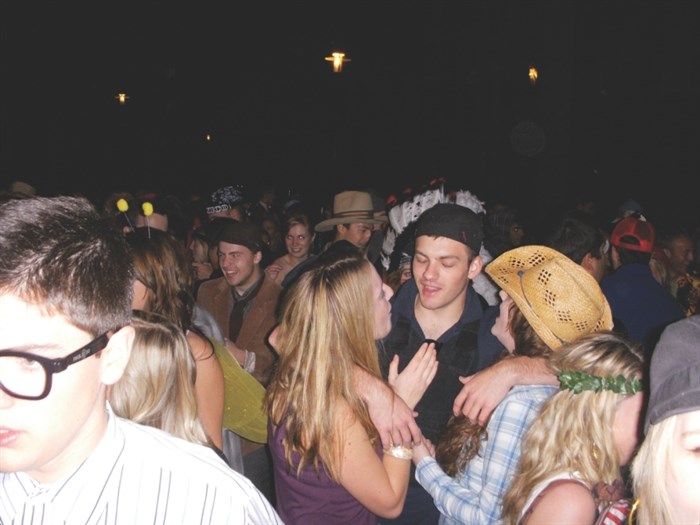

Students dressed as Na’vi from the movie Avatar for a Halloween street party on the UBC Okanagan campus in Kelowna in October 2010.

Image Credit: The Phoenix/Ali Young

October 12, 2014 - 2:29 PM

KELOWNA - As a 19-year-old in his second year of university, the Cascade street parties were surreal to me — they were a college movie come to life. On any weekend (the warm ones at least) you could walk out of a rez room and immediately be swept up in a swarm of woo-girls and fist-pumping beer-shotgunning bros, who all milled about the buildings meeting new people. They jumped off ledges and balconies; climbed gazebos; and navigated the police, security, and RAs who all posed a threat to their freedom of underage and/or public drinking.

That chaotic culture is gone now. Parties still happen but they’re fewer and further between. The sanctioned parties are growing stronger to fill that void, as the UBCSUO gets more organized. Police and Security confirm that things have improved dramatically from their perspective. But what happened to the glory days of UBCO’s party scene, and why did it change?

If you build it, they will party

“UBCO was massive for parties in my first two years,” said Ian Lauzon, a graduate of UBCO, “the roads of phase two and three were like Mardi Gras on the weekends and you were free pretty much to drink outside. Most RAs were pretty relaxed with it as long as you weren’t causing trouble. The Cascades dorm parties were always quite hilarious and drew in huge amounts of people.”

Those street parties were the first thing you’d see, but they weren’t the only game in town. “People seemed to care nothing about school in the first month of school,” said Lauzon, “it was all about the beach and having huge campfires up on the hill above campus.

Lauzon was referring to the parties above R Lot at the top of the university, past where the Upper Cascades are perched. They would often get busted (smoke in the Okanagan doesn’t go unreported for long) but students could easily scatter like ants down a hill into dorms and find their next adventure for the night.

“There were keggers being thrown by engineering or H-kin [students] in the woods,” said Lauzon, “the Redbull party at Postill Lake Road was also out of this world. I mean, school buses taking kids to the party is ridiculous.”

The Postill Road party was organized by students and sponsored by Redbull—they bussed ticketholders up there and let them loose on unlimited beer while the Redbull car blasted music and a bonfire raged. I remember spending most of that night wandering the outskirts of the crowd in disbelief that the whole thing was happening. As if they’d read my mind, half the conversations I had there, and overheard, were just about the party itself.

Another regular event was the beer pong tournaments held in the woods above the university, near Quail Ridge. Lauzon was one of the students who organized them. Other notorious party spots included the “bro farm,” located across the highway from campus, and the quarry.

“They used to go up to the quarry and have a bush party,” recalled Well Pub Manager Mike Ouellette. ”They used to have something they called ‘yukkaflux’. They would fill a cooler of vodka and stick a bunch of fruit in there, and marinate it and inject it, and they would eat the fruit that night. And people would just get so drunk. It was really dangerous actually.”

Meanwhile, some dorm parties bore more similarities to dance clubs than campus residences, complete with DJs and disco-ball-esque lighting. Usually it was these student-run, unsanctioned events that drew you in with the promise of the most fun, but even some of the legitimate parties became notorious.

I admit I loved the whole thing; the sheer number of people, opportunities, and the independence of it—it was like a network of parties to explore, each with their own unique qualities.

One fourth-year student I interviewed shook his head wistfully as he reminisced. “You come here to learn first, but back then it definitely didn’t seem like that.”

One of the beer pong tournaments held in the woods above the UBC Okanagan Kelowna campus.

Image Credit: The Phoenix/Ian Lauzon

The turning point

UBCO did crack down eventually. It was 2008 when things came to a head with a large police crackdown, and it became near-impossible to find a large-scale on-campus dorm party for the rest of that year since cops or security would shut things down by 11 p.m. at the latest. You’d be on your way over, your phone would ring, and you’d be listening to the dejected voice of a friend telling you to turn around.

The party scene wasn’t to be broken so easily though, and it continued in the over the next two years as major dorm and street parties remained active for at least the first two months of the school year, culminating in final big events on Halloween in which students would mill on the street in costume (and often in character).

After the stabbing in September 2011, though, things changed more permanently. Administration took an even closer interest.

“With the understanding of the SU and others we’ve enhanced our video coverage and patrols; all of that was reviewed in the discussion with the RCMP, Security, and the SU,” said Doug Owram, the Deputy Vice Chancellor at the time of the violent event. The people involved turned out to be from off campus, but it was still a big blow to the reputation of UBCO, demanding a response.

Students noticed the shift. “The school cracked down on [parties] since the stabbing… That’s the general consensus,” said Nate Speijer, a six-year student and 2013-14 captain of the men’s Heat volleyball team who graduated in June.

With UBCV peering over its shoulder, UBCO was already on thin ice, so any incident would aggravate that dynamic. The slow-boil of the growing party culture had made things edgy already, and the stabbing was the climax.

UBCO’s underdog status was recently reinforced by a post on the Ubyssey’s social club blog, responding to the sticker war UBCO seems to be waging at UBCV. CJ Pentland wrote that “after constantly living in the shadow of their Point Grey sibling, repeatedly losing in sporting events and living with the reputation as being a home for UBC-Vancouver rejects, it appears they’re finally going after us.”

A Cascades quad room at the students residence on campus at UBC Okanagan in Kelowna filled to bursting with students.

Image Credit: The Phoenix/Ali Young

How did the party culture start in the first place?

Although it’s a ridiculous notion to draw a direct parallel between the two campuses (UBCO is only 8 years old, compared to UBCV’s 106 years, not to mention the size difference), the shared UBC name will always cause comparisons, and Pentland is correct about the reject mentality. Even administratively, a system was put in place in order to fill seats at UBCO by giving secondary offers to students who were turned away from UBCV, which clearly connotes UBCO as a second-rate alternative. In that context, it’s easy to see why UBCO would be even more eager to crack down hard and fast.

UBCO is getting its feet under it though. In 2014, coinciding with the drop in partying, seats have been filling up, so there will no longer be any domestic ‘Vancouver rejects’ offered.

“This year for the first [time] we aren’t going to make what we call ‘third choice offers’ to domestic students,” said Ian Cull, AVP Students at UBCO. He explained that it had been done in the past because the Provincial Government paid money for each seat filled, so they were in a rush to do so. Those third choice offers will still be made to international students who are turned down from Vancouver, however.

Ultimately, it’s easy to see how UBCO became a party school:

The campus was under a mandate to increase its population. This move not only necessitated relatively lenient academic entry requirements, but also added bodies faster than there was time to complete the physical or social infrastructure for them. These new bodies also tended to belong mainly to first-year students, who were too young to legally get into bars and who were often away from home for the first time.

The campus was located out of town and near the woods, making it easier for students to throw bush parties, harder for cops to monitor the area, and less likely that the public would notice and complain about noise and/or debauchery.

The campus was marketed in part as a lifestyle destination near to sun, sand, and snow, meaning that many students likely came here intending to have fun. (Even if these were not the primary selling points for the school itself, Kelowna still has its own recreation and party reputations)

Together, these and other conditions created a perfect storm for a party school.

Partygoers on top of the wooden structure in Lower Cascades student residences on the UBC Okanagan campus in Kelowna.

Image Credit: The Phoenix/Ali Young

UBCO is sorry for party rocking

As one fourth-year student put it: “You could definitely see the decline in my second year, [the parties] definitely weren’t as strong. I think that was largely due to increase in admissions standards in a lot of faculties. The upper years were the ones who had come here and established that party school. You could tell there was a new wave of people that were more focused on school than the social aspect.”

As unsanctioned student-run parties die off, organized parties may be the future of partying at UBCO—Frosh week is gaining momentum, and this year the SU launched the year-end concert “Recess.”

“There are more planned events now,” Speijer said, “but as far as number of people in attendance, giant rez parties, Cascade street parties, those don’t happen anymore.”

“Admin is locking down on people… [students are] more afraid of getting in trouble, and of more consequences.”

Those consequences become clear by looking at the non-academic disciplinary reports. Seven of UBCO’s eight non-academic disciplinary reports for 2012/2013 were regarding alcohol. In comparison, UBCV’s non-academic disciplinary reports included just three: one assault, one laptop theft, and one sexual assault. Keep in mind the relative size of the campuses: approximately 8,500 students compared to 50,000. And yet UBCO has almost three times as many non-academic disciplinary cases.

Security and facilities did not have any figures or yearly reports on hand to show us, but both departments agreed with the anecdotal testimony of students as to party culture. “Some unsanctioned events do still happen, maybe around Halloween…but it has definitely gone down,” said Roger Bizzotto, Associate Director of Facilities Management. “We have a better reputation, I think that it’s been a good improvement, it’s been a good stabilization for us at the campus.”

UBCO’s Director of Parking and Security, Gary Appleton, added that the bush parties just don’t happen like they used to. Appleton attributed any success from security to their integration into the community and education of students, as the department did not even keep up with the campus growth, relative to student body. According to Appleton, security has gone from two guards on shift to three (50% increase) in the time that the school has gone from 3,500 students to 8,500 (140% increase).

RAs also confirm the trend. “There are still get togethers for pre-drinking,” said one RA, “but people are leaving campus for the wilder parties…it quiets down around 10 or 11 p.m. most of the time. There are also noticeably [fewer] noise complaints. The only time there ever is is when they are pre-drinking but they are usually very cooperative.”

In the 2010/2011 academic year, there were 487 incident reports filed by RAs. In 2011/2012, that went down to 484, while the beds on campus increased by 214 from 1,462 to 1,676. Then in 2012/2013, incident reports plummeted to 263. According to Shannon Dunn, Director of Housing at the time of those reports, there was no change in the housing rules or how RAs give out incident reports to help explain the drop either. So while the number of students living on campus increases, incidents reports are heading the other way.

As for the police, they conveyed to us at the beginning of this year that the September parties were tame compared to previous years. The service calls from residence mirror the firsthand accounts of students:

-From September to March of 2008, there were 96 calls from campus to the Kelowna RCMP detachment.

-The next year it increased to 129; and then again in 2010/2011 to 193.

-The last increase was in 2011/2012, when it peaked at 231.

-After that crackdown in 2011/2012, the calls dropped by 40% to 138 in the same period, and stayed steady at 144 for 2013/2014.

Hundreds of revelers celebrate Halloween 2010 out on the street in Cascades student residences.

Image Credit: The Phoenix/Ali Young

Onwards and upwards

Alcohol and partying will remain a staple of university campuses.

“Meeting new people is always difficult,” said Jeremy, “alcohol was a great way to break down those barriers.” That innocuous use of alcohol snowballed at UBCO, and in its attempt to correct a problem and save its fragile reputation, the school may have swung the pendulum further towards conservatism.

“There was definitely a negative stance from the school on these parties,” continued Jeremy, “[but] we had a good balance between fun and respect. It was really a good way to meet everyone, and it was good for school spirit.”

That school spirit seems to be the difficult balance to reach. How is it achieved, like at Queens University (homecoming anyone?) without letting the partying get out of hand and hurting the school’s reputation? UBCO lacks a strong campus culture— it’s a serious problem for a campus on the outskirts of town without enough non-academic commons space for students. The new Well has picked up in its day business, which has helped, but there is still very little for students to do here except, well, leave.

University is an odd beast. It’s a live-action social experiment of ‘hey let’s put all these young hormonal kids in an adult environment and see what happens.’ They’re doing a ton for the first time: feeding themselves, dealing with classes that are ten times harder than what they’re used to, and managing unlimited access to co-ed opportunities and various intoxicants. Oh, then add in early UBCO’s minimal infrastructure, fringe campus, and explosive student growth, of UBCO and it’s no wonder the party culture developed.

In his final town hall, outgoing UBC President Stephen Toope spoke to the problems specific to UBCO, and how far the campus has come: “I remember well coming for my first visit here, and thinking that this was a fragile place…it doesn’t feel fragile at all now.” He conveyed that there had also been a sense of worry about how UBCO would fit into the UBC umbrella. But he said that’s coming to an end.

UBCO is getting its academic feet under it, and it’s beginning to live up to the esteemed UBC name. The problem remains that there is little campus culture, however. The party culture wasn’t replaced—it left a void. The void is being filled little-by-little, with everything from Karma Bowl lunches to theatre performances to beer gardens, but it’s nowhere near the kind of vibrancy you see at other university campuses. It has more parallels to a community college where students get in and get out. The sun set on UBCO’s party empire, and from its ashes hopefully a middle ground can emerge that allows a culture to develop that students and administration alike can be proud of… but that feels a long ways off, still.

To contact the editor, email mjones@infonews.ca or call 250-718-2724.

— Editor's note: This story was orginally published in UBC Okanagan online newspaper The Phoenix and is republished by Info News with the permission of the author.

News from © iNFOnews, 2014