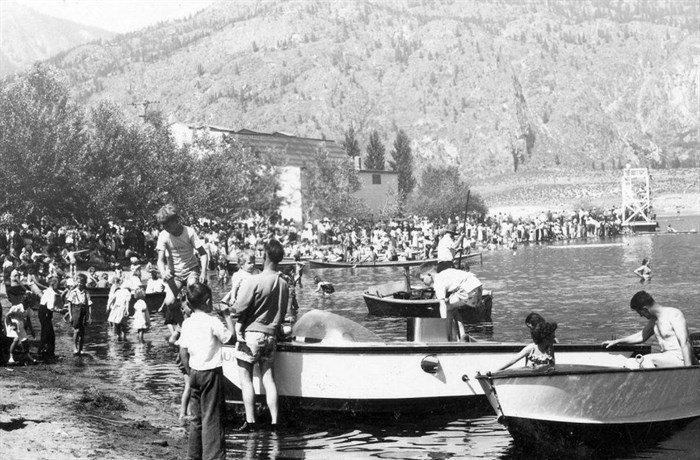

The community beach was crowded with people at the first Cherry Carnival in 1949 featuring aquatic events.

Image Credit: Osoyoos Museum and Archives

February 07, 2021 - 10:00 AM

On Jan. 14, 1946 the small village of Osoyoos became a municipality. The first ever meeting of the Municipality of the Village of Osoyoos was held at the Canadian Pacific Railway station a few weeks later and William Andrews was elected chairman of the board, Gordon Kelly and Joseph Armstrong were elected village commissioners.

In 2021, the Town of Osoyoos is celebrating its 75th anniversary as a township.

In the early days of the village, severe flooding in the area led to the channelization of the Okanagan River. Houses in East Osoyoos were surrounded by water during the flood of 1948, one of George G. Fraser’s earliest memories. When he was eight years old, there was a week when he and other students had to hop on a boat on their journey to school in Oliver.

“We lived on the east side, and the bridge that is there now is a replacement of a couple of earlier ones and it's considerably higher than what was there in 1948. So for just about a week, I had to take a boat from where we lived over to town a catch the school bus there. Because at that point, we were being bused to Oliver,” said Fraser.

Fraser, who is still an Osoyoos resident today, is the grandson of George J. Fraser, who authored “The Story of Osoyoos: September 1811 to December 1952.”

“He was George J. and I was George G., so that was the separation,” Fraser said with a laugh.

READ MORE: The history of Osoyoos from two very different perspectives

George J., originally from Alberta, came to Osoyoos in 1917 when the population “jumped from 13 to 17,” Fraser joked. A combination of goings-on in the town, historical events and personal history, George J.’s book would become one of the earliest documentations of activities in what would eventually become the Town of Osoyoos.

“I think because he had been here so early, and a great part of the changes that took place, I think he felt it important to document it,” Fraser said.

Aside from taking a boat over flood waters to get to school, Fraser recalls Osoyoos as a village that was “very friendly, very small” in the early days.

The Canadian Pacific Railway would come to Osoyoos in 1944, a memory that stands out for Fraser as he was on the opening run of the new line.

“That was kind of neat and for me, it stood out because they ran, I think, two passenger cars onto the locomotive to Penticton. And we got to ride all the way down from Penticton to Osoyoos. Sort of the opening run kind of thing. My parents and (I) were on one. I have no idea who else of course," Fraser said with a laugh.

The population of the small village would continue to grow, with 899 people living in Osoyoos in 1951 around the time when Gayle Cornish and her family moved to Osoyoos from Port Coquitlam. Her earliest memory of Osoyoos includes former landmark water towers that no longer exist.

“We lived in a small house on Highway 97 and the first day I went to school I got lost very far from where we lived, just close to where the water towers were at that time. So that's one of my first memories," she said with a chuckle. "But the water tower was always kind of a landmark.”

She recalls Osoyoos as a lovely small village where “everyone knew everyone” and celebrations for Christmas as well as the annual Osoyoos Cherry Carnival, known today as the Osoyoos Cherry Fiesta.

“It was a really good community and we have a lot of good memories from July 1, which has always been celebrated. At that time, it was the Osoyoos Cherry Carnival and it was a very special day for all the kids in town.”

When a group of Osoyoos residents got together in the spring of 1949 to plan the community’s first Cherry Carnival, the idea was to hold an aquatic sports day to raise money for park development. Cornish recalls swimming and raft races and plenty of summertime days on the lake, experiences she would later turn into a career as a swimming instructor and life guard for many years.

“There was a children's parade, which started first, so a lot of children decorate their bikes and wagons and so forth. And I remember, we made a covered wagon, a chuckwagon, and put our wagon in the parade. I guess I was in Grade 2 or 3 at the time. And then everybody went down to the community hall and it was just a great day.”

Cornish recalls many of the students she went to school with at the time often worked on their family’s farms. The economic focus in the community at the time revolved around fruit orchards.

“One thing I remember quite clearly is there were two packing houses in town and everyone had a connection to the packing house. Everyone worked there. When I was 13 I worked at the packing house sorting cherries,” Cornish said. “Nowadays that wouldn't be allowed, but then if there was a run on cherries they needed you to come and help. And so that was where, I think, I got my first paycheque was from the packing house.”

The main packing house, one of a few in Osoyoos, was located where the Watermark Resort stands today at the end of Main Street. It was in operation until the 1980s and the building remained vacant through most of the 1990s right up until the Watermark was built. It was a key to agriculture in the area, said Kara Burton, executive director of the Osoyoos Museum and Archives.

“The train station and the train tracks were right there coming to the packing house so fruit and everything could be shipped out quite easily,” Burton said.

The economy would inevitably transition with trains no longer coming into town in the 1970s and the tracks removed in the 1980s. Osoyoos began shifting from majority fruit orchards to the vineyards and tourist-hosting hotels of today.

“The orchards were prominent then,” Cornish recalled. “And now of course, it has switched around and vineyards have been taking over for the last 50 years. So it's quite a change in the landscape.”

Prior to the Osoyoos Secondary School opening in 1979, there was only one high school serving the Oliver and Osoyoos area, seeing around 800 to 900 students. Much like the rest of the world, Osoyoos was not immune to racism. Chief Clarence Louie of the Osoyoos Indian Band recalls drop-out rates were higher with Indigenous students at that time.

“Most of the band members would quit school because they couldn’t put up with the racism and it’s not that they were scared of white people. I always say that the white kids had a deep respect for the kids from the Osoyoos Indian Reserve because they know if they picked on the Rez kids the Rez kids would beat them up,” Louie said.

“There can be quiet racism where you know you’re not included and you know you’re not welcome. The drop-out rate was pretty high back then. Kids know when they’re not welcome.”

Louie said he didn’t personally experience much direct racism and touts sports for being a great way to bridge the cultural gaps between communities, but he said he doesn’t see as many inter-community leagues today.

“When I was going to school there in the ‘70s there was what I would call just Indians and whites. I never got picked on, I didn’t notice any racism because I was involved in sports,” Louie said.

“Sports whether on reserve or off has gone down, down, down. Back in the ‘70s and ‘80s sports used to be a big thing. The men’s hockey league in Oliver used to be a big thing. All the Rez boys got to know the white kids in town because we played hockey or basketball with them. There’s no more basketball league, there’s no more men’s hockey league. Sports has gone down in this town which really sucks … maybe soccer has gone up,” Louie said. “A lot of relationship building to me comes through sports. A lot of racism can be broken down through sports. All the boys who played hockey, the white guys in town, had a mutual respect because we played on the ice together.”

The Osoyoos Indian Band has been celebrated for its successes as a business enterprise in the past few decades, with Chief Louie leading those efforts to bring economic growth to his community. The OIB owes some of its success to the location of the band’s land, Louie said.

“Even though we had 4,000 acres of our best land stolen, we still had land from which to work with. Even though most of our reserve land is hills and mountains and rocks, we still had some decent land from which to work with,” Louie said. “A majority of my people want to work for a living and they want good development that provides jobs, an income for the band. It’s no different than the mayor and council (of Osoyoos).”

Today the economies of the OIB, Osoyoos and Oliver are greatly intertwined and there are far more job opportunities on the OIB today compared to the early days of Osoyoos.

“What I find kind of neat is so many white people now make a living off of Osoyoos Indian Reserve land where they work at the prison, Spirit Ridge or Area 27 or the wineries, or the upcoming wine village,” Louie said.

“That’s a big reversal.”

Despite the origins of colonialism possibly putting up barriers in the past, the business relationship between the OIB and the surrounding communities is good today, Louie said, and people from outside of the OIB are now enrolling students in the Sen’Pok’Chin School on OIB land, building homes and working on the Osoyoos reserve.

“They’re even bringing their kids to our daycare on the reserve and bringing their kids to our Rez school on the reserve that started in the 1990s,” Louie said. “We have a health clinic here now too and it’s the first time I’ve ever seen in my life where Oliver people are coming to the reserve not only for pre-school and schooling now, but they are even coming to the reserve to see the doctor at our health clinic. That I’ve never seen before and that’s only been recently.”

— This story was originally published by Times-Chronicle

News from © iNFOnews, 2021