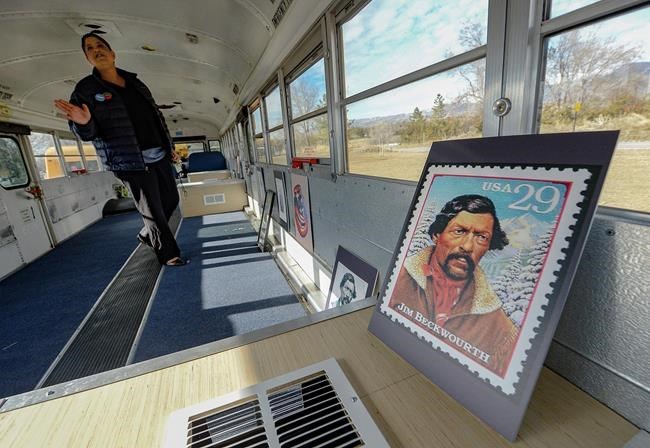

Lex Scott, leader of the Black Lives Matter movement in Utah gives an update on Tuesday, Feb. 26, 2020, on plans to renovate an old school bus into a mobile black history museum to visit schools around the state and teach African American history. She hopes construction is complete by the end of March. (Francisco Kjolseth/The Salt Lake Tribune via AP)

March 08, 2020 - 9:54 AM

SALT LAKE CITY - The Utah State Railroad Museum in Ogden has a permanent display about black railroad workers who ended up settling in the area. The new Black Cultural Center at the University of Utah created campus exhibits about influential African Americans last month — but its focus is providing resources and support.

Other temporary installations crop up elsewhere, such as Brigham Young University, especially during February. But that’s about all there is if you want to go somewhere in Utah to learn about black history.

And that’s where this gutted school bus comes in. Lex Scott, the leader of Utah’s Black Lives Matter, is standing inside it, her head just inches from the roof.

“The goal is brick and mortar,” she said, but with the bus, “we want to give people a taste of black history.”

It’s carpeted on the inside, save for a walkway down the middle, and all but four seats, a pair at the front and back, are gone. Posters of portraits are adhered to the wall. Still to come: a TV to hang in the back and display cases for the artifacts Scott has collected at the organization’s headquarters.

A decorative wrap is planned for the exterior. Then voila: It will be a Black History Museum on wheels, bringing the stories of black Utahns and Americans to schools, events, businesses and churches.

Robert Burch, president of Utah’s Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, said his group and others have been trying to buy a building for a museum dedicated to black history for years. When Scott first pitched the bus idea in 2018, he said, it was the first renewed effort in about 15 years.

He said it would mean a lot to the black community in Utah, and reflecting the state’s diversity could make it more welcoming.

“With no permanent place affixed in a city or online that black folk can go to and say, ‘Oh look, you can go to Utah. There’s plenty of black people in Utah,’” he said, “without that, we can’t get people to feel that (and move here).”

The U.S. Census estimated that in 2019, only 1.4% of the more than 3 million people living in Utah were black. Burch said it can sometimes feel like there aren’t any black people here — and that they weren’t ever here.

The lack of a museum dedicated to black history implicitly affirms that. But there’s plenty of black history in Utah, he said.

For starters, black people were in Utah before the first pioneers with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints arrived, mostly collecting furs in the early 1800s. One of the most notable of those trappers was James P. Beckwourth, who spent several years in Cache Valley. He’s featured in the bus.

“It’d make a difference for the local community, not just the black community, to recognize that black folks were here before even the Mormons were here,” Burch said.

Fort Douglas, perched high on the U.’s campus, hosted an entire regiment of black soldiers beginning October 1896. Their service brought about 600 African Americans, including women and children, to Salt Lake City. As historian Jeffrey D. Nichols wrote, the arrival was an “important change in the racial makeup of (Salt Lake City’s) population.”

As part of celebrating suffrage anniversaries in Utah this year, the non-profit Better Days 2020 has highlighted several African American women — including early newspaperwoman Elizabeth Taylor and Mignon Barker Richmond, the first African American woman to graduate from a college in Utah, in 1921.

Burch said that efforts to create a museum typically fall short because of funding issues. He said he’s looked at property in downtown Salt Lake City that costs millions, and he and his group don’t have that kind of money.

“I feel like one of the reasons we have a hard time with African Americans moving here and leaving is they don’t feel like Utah is a shared place,” he said. He’s hoping for “an opportunity to build a museum, a place that even visitors can come and feel like, oh, there is black history in Utah.”

Meligha Garfield, the director of the U.’s Black Cultural Center, said the erasure of black history weighs on him after seeing how much space is dedicated to teaching Latter-day Saint history, and on a smaller scale, Native American history, in Utah.

“It kind of says that we’re invisible, and that Utah in a lot of instances is comfortable with us being invisible,” Garfield said.

Garfield has helped put together multiple interactive exhibits dedicated to black history at the U. this Black History Month. Viewers were invited to write notes about their reactions to quotes from black leaders.

He said his team is also working to create a small library that carries limited edition books on black history, like an original 1976 copy of “Roots: The Saga of an American Family.”

At the Black Lives Matter headquarters in Murray, behind a door labeled “Wakandan Embassy,” Scott keeps some of the artifacts she’s come across. She grabs one off a table, a racist caricature of a black person’s face.

“So, this is from Coon’s Chicken Inn,” Scott says, a restaurant in Sugar House that closed in 1957.

The door to the eatery was a scaled-up version of the knickknack, requiring patrons to walk through the 12-foot-tall face, painted dark brown and winking, with a big toothy smile framed by huge red lips.

Scott found this relic at a local antique store. She finds lots of other “super duper racist” things there, too, when she meets with the owner once a week.

The plan is to line one side of the bus with items related to Utah. The other side will focus on U.S. black history. In the back, Scott says, a TV will play an introduction to the bus for everyone who enters. It’s been over a year since she purchased the bus, and the interior renovations will be done by the end of March, she estimates.

Burch said he’s supportive of the bus, but he’s going to continue working on his goal to buy a building where artifacts can be kept safe in a climate-controlled environment. That’s Scott’s dream, too.

Until then, she’ll just keep the bus’s wheels turning.

News from © The Associated Press, 2020