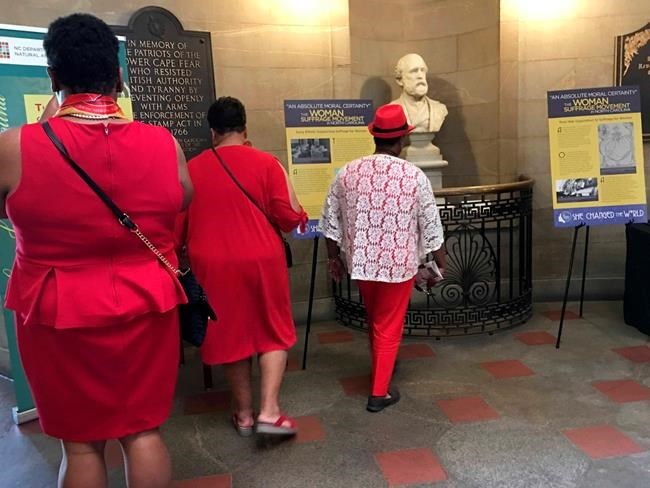

FILE - In this Sept. 7, 2019, file photo, visitors look at items marking the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment, at the State Capitol in Raleigh, N.C. The exhibit was titled, "She Changed the World: NC Women Breaking Barriers". (AP Photo/Martha Waggoner, File)

Republished August 25, 2020 - 5:52 AM

Original Publication Date August 18, 2020 - 12:51 PM

HARTFORD, Conn. - As the U.S. marks the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, many event organizers, mindful that the 19th Amendment originally benefited mostly white women, have been careful to present it as a commemoration, not a celebration.

The amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified on Aug. 18, 1920, but many women of colour were prevented from casting ballots for decades afterward because of poll taxes, literacy tests, overt racism, intimidation, and laws that prevented the grandchildren of slaves from voting. Much of that didn’t change until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

From exhibits inside the Arizona Capitol Museum to a gathering on the North Carolina Statehouse lawn, many commemorations, including those that moved online because of the coronavirus pandemic, have highlighted a more nuanced history of the American women’s suffrage movement alongside the traditional tributes to well-known suffragists such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

The 100th anniversary has arrived during a year of nationwide protests against racial inequality that have forced the United States to once again reckon with its uncomfortable history.

“Like many movements, the stories are complicated and I think it’s important, as we have an opportunity to reflect and to celebrate, that we also are honest about how we didn’t meet all of our aspirations,” said Rhode Island Secretary of State Nellie Gorbea, a Democrat born and raised in Puerto Rico who has helped to organize her state’s suffrage commemoration efforts. “It’s important to have these conversations so we can do a better job of going forward.”

The Connecticut Historical Society last month unveiled an online exhibit titled “The Work Must Be Done: Women of Color and the Right to Vote.” It highlights Black women from Connecticut who fought for suffrage rights as well as other issues, such as anti-discrimination, anti-lynching, labour reforms and access to education.

“We have really been wanting to make sure we talk about the complicated history of these issues in our country,” said Arizona Assistant Secretary of State Allie Bones, whose office came up with a program after working with about 60 community groups across the state, many of which were “very focused on not calling it a celebration, but ... a commemoration.”

The complicated nature of the suffrage movement came full circle last week when Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden chose California U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris as his running mate, making her the first Black woman on a major party ticket.

In an appearance with Biden last week, Harris said she was “mindful of all the heroic and ambitious women before me whose sacrifice, determination and resilience makes my presence here today even possible.”

While their names are not as well-known as the white suffragists, Black women played both prominent and smaller roles in the movement. Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave, who died in 1883, is considered one of the first known Black suffragists. She travelled throughout the U.S. speaking at women’s rights conventions and suffrage events, including at the Akron, Ohio, women’s convention in 1851 where she was credited with giving a powerful speech that’s been remembered as “Ain’t I a Woman?” Some historians, however, have questioned the wording.

Through the years, there were many prominent Black abolitionists and suffragists who worked in their own women’s clubs and suffrage organizations and sometimes side-by-side with white suffragists, often working for both voting rights and civil rights.

The young founding members of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority participated in the 1913 suffrage march in Washington in their first public act. The Howard University students took great personal risk and were not being welcomed by some white suffragists who ultimately insisted the Black women march at the end of the procession, said Cheryl A. Hickmon, national first vice-president of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.

“They felt that it was their obligation, if you will, even though it was unsafe to march with the other women and show their dissension and feelings,” said Hickmon, whose organization has been working with organizers of the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial that’s being constructed in southern Fairfax County, Virginia, and includes an overview of the entire movement, including Black suffragists.

The 100th anniversary marks an opportunity to “honestly examine” the relationship between white and Black women in the women’s rights movement, said Johnnetta Betsch Cole, a former college president and anthropologist who is currently the national chair of the National Council of Negro Women, an organization that was founded in 1935 to advocate for women’s rights.

“There is more acknowledgement of the complexities of the strains, of the racism in the suffrage movement than ever, ever before,” Betch Cole said. “Unfortunately, one can be victimized in one form of oppression and then turn around and victimize others on another basis.”

In June, protesters in Iowa demanded that Iowa State University remove the name of suffragist and alumna Carrie Chapman Catt from a building because of white supremacist and anti-immigrant statements attributed to her.

Doris Kelley, a former Democratic Iowa House representative who chairs the state’s 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration, said it’s important to remember the historical context that suffragists navigated while acknowledging the movement’s complexities. The logo of Iowa’s centennial commemoration “Hard Won, Not Done,” Kelley said, is a nod to that unfinished history.

In North Carolina, Janice Jones Schroeder, a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, said she was impressed that organizers of the state’s suffrage anniversary activities thought to include her in a commemoration event last September on the lawn of the Statehouse.

“At that time, American Indians were not even considered citizens of the United States,” she said. While the Snyder Act of 1924 admitted Native Americans born in the U.S. to full U.S. citizenship, it was left up to the states to decide who had the right to vote, and it took more than 40 years for all 50 states to agree to grant them voting rights.

Schroeder said there are still challenges today for tribal members who want to vote, including voter ID laws, long distances to register to vote on some reservations, lack of access to mail and socioeconomic disparities.

Women of colour in African American, Latino and other communities face similar barriers, making the anniversary of the 19th Amendment and the ensuing decades-long fight all the more relevant a century later in a high-stakes election year.

“I look at politics now,” said Schroeder, “and I think, ‘Do we still have a voice?’

___

Naishadham reported from Atlanta.

News from © The Associated Press, 2020