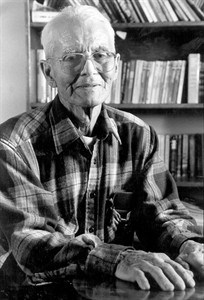

FILE -- This Feb. 1984, file photo shows Edgar Paul Nollner, who died Jan. 18, 1999, in Galena, Alaska. Nollner, 94, was the last surviving musher of the famed 1925 Nenana, Alaska to Nome, Alaska diptheria serum run that later inspired the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. In January 1925, sled dog relay teams delivered the serum after a deadly outbreak of diphtheria in the old gold rush town of Nome on the state's wind-pummeled western coast. The 5 ½-day run is detailed in "Icebound," a documentary by New York filmmaker Daniel Anker. The 95-minute film, narrated by actor Patrick Stewart, is opening the Anchorage International Film Festival on Friday, Dec. 6, 2013. (AP Photo/The Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, Mike Mathers, File)

December 05, 2013 - 1:40 PM

ANCHORAGE, Alaska - A deadly epidemic had gripped a gold rush town in the impenetrable U.S. territory of Alaska nearly 90 years ago, transfixing the nation.

A cure existed, but there was no way to deliver it. There were no roads available, and air supply drops weren't an option.

The only solution was a nearly 700-mile sled dog relay to deliver a life-saving serum to those threatened by the 1925 diphtheria outbreak in the rugged coastal town of Nome.

A new film, "Icebound," documents the race against death and will debut at the Anchorage International Film Festival this week. The 95-minute picture is narrated by Patrick Stewart, and a national theatrical release is set for next spring.

Eight years in the making, the film details the rescue efforts, using black-and-white photographs and film footage, interviews with survivors and descendants, modern mushers and historians, and longtime Alaska journalists.

"It's a small moment in history for which you can extrapolate all these larger truths about American culture," said filmmaker Daniel Anker.

The documentary revives a story that captured the nation's imagination from radio and newspaper reports — including dispatches from The Associated Press — telling of the drama playing out in the frozen north, where temperatures plunged to 50 below that long-ago January.

The first of two supply runs took five days, and the saga quickly reached mythic proportions. Months afterward, a bronze statue of the sled dog Balto went up in New York's Central Park.

"One of the things that's really interesting about this story has to do with the technology and what the technology could and couldn't do," said David Weinstein, senior program officer for the National Endowment for the Humanities. "Ultimately, the only way for this to work was through dogs, through an older technology."

Weinstein's agency provided $695,000 to fund the $1 million project.

Diphtheria is an airborne disease that attacks the upper respiratory system and has been largely eradicated.

But in Nome, Alaska, in 1925, it was a deadly threat. The official medical record counted five deaths and 29 stricken residents. However, many believe that deaths among Alaska Natives were never accurately tracked during a time when they were segregated from Nome's white residents.

Balto, namesake star of a 1995 animated film about the outbreak, became famous out of scores of other dogs because he was a lead canine on the last leg of the first relay.

The dog was an unlikely hero. Balto was a freight dog owned by a champion musher of the time, Leonhard Seppala, a Norwegian who lived in Nome. But he never made Seppala's competitive teams of Siberian huskies because he was too slow.

Gunnar Kaasen, another Norwegian and Seppala's assistant, drove the final leg of the first supply run. Kaasen was supposed to hand off the last dash to sprint champion Ed Rohn for the final stretch to Nome. But Kaasen led the team all the way in. He said later that no lights were on at a cabin where Rohn was waiting, and he didn't want to waste time.

Historians say Balto and Kaasen received a lion's share of the fame that should have gone to Seppala and his 12-year-old lead dog Togo. Also, lost in the hoopla were other dogs and mushers — many Alaska Natives among them — who took part in the relay. They included Athabascan and Inupiat Eskimos.

Seppala's team travelled more than 200 miles of the relay, including a treacherous 20-mile trek across the frozen Norton Sound. Kaasen's team travelled a little more than 50 miles, some of that, however, in a severe blizzard.

"While it was going on, much of the coverage seemed to be focused on Seppala because he was the champion musher," said Anker, who was nominated for an Academy award in 2001 for another documentary, "Scottsboro: An American Tragedy."

"When Gunnar Kaasen made his surprise appearance in Nome," Anker said, "well, it was a perfect opportunity to generate more and different stories."

___

Follow Rachel D'Oro at https://twitter.com/rdoro

News from © The Associated Press, 2013