(CHARLOTTE HELSTON / iNFOnews.ca)

August 22, 2021 - 12:00 PM

This feature first ran on iNFOnews in April of 2017.

VERNON - For much of the year, home for Dag Aabye is a portable garden shed that he carried, in pieces, halfway up a mountain to a remote location in the woods.

His home base has no cell service, running water or electricity, and is located about an hour’s hike from the nearest highway, up a trail only Dag knows how to find. The 75-year-old makes the trek up and down regularly throughout the week. He takes public transit and loads his backpack full of coffee, potatoes, eggs and other staples that he’ll cook up over a fire.

I got to know Dag this past year over several long coffees and a longer hike to his special spot on the mountain. I was intrigued by Dag before I even met him. I’d long heard stories of the tough Norwegian who jogged up and down the steep switchbacks of Silver Star Road for a casual morning jog. I skied past the double black diamond run named after him at Silver Star Mountain (it’s called Aabye Road), and read about his participation in Alberta’s annual Death Race — a 125 km adventure race that spans three mountain summits. Finishing the race is a feat at any age; in your 70s, it's astonishing.

I knew I wanted to interview him, but I had to find him first.

Dag is not someone you’ll find in the phone book. He doesn’t have a fixed address, a cell phone, or email. But, he has lots of friends for someone who lives alone in the woods, and after several phone calls and a message left for him at a local sports bar, he called me back from a payphone.

'NEVER DIE EASY'

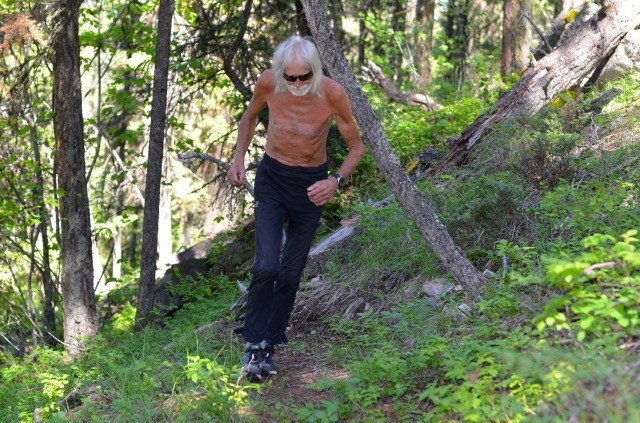

Dag runs along one of the trails he built in the North Okanagan backcountry.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON / iNFOnews.ca)

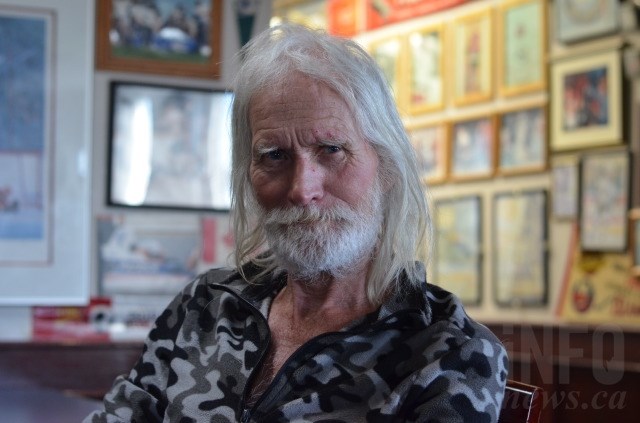

Dag takes a sip of coffee from the same mug he always gets at Roster Sports Club Bar and Grill in Vernon. The words ‘Never die easy’ are emblazoned on it — fitting for a man who figures he’s had about 30 brushes with death.

“I sat down one day and started writing them down. After 27 I said ‘okay, this is getting scary,’” he says.

They include logging accidents, falling into a river at 12 years old in Norway, and skiing an avalanche down The Lions — a pair of mountain peaks along the North Shore Mountains in Vancouver. He landed in a tree well, and a photo of the miraculous, near-death moment made it onto the front page of the Vancouver Sun the next day.

“I’m not afraid of dying because I’m not afraid of living,” Dag says.

He's been chasing challenges all his life, never sitting still longer than it takes to finish a pint of beer. There's always something to do, always another hill to climb.

Dag is built like a pair of scissors — long, slim legs that cut through the air. He’s a lean 6’2” and wears his wispy, white-blonde hair chin-length. He cuts it himself. His wardrobe — folded neatly and kept dry in numerous rubber bins — includes a large collection of Death Race T-shirts and high end performance gear.

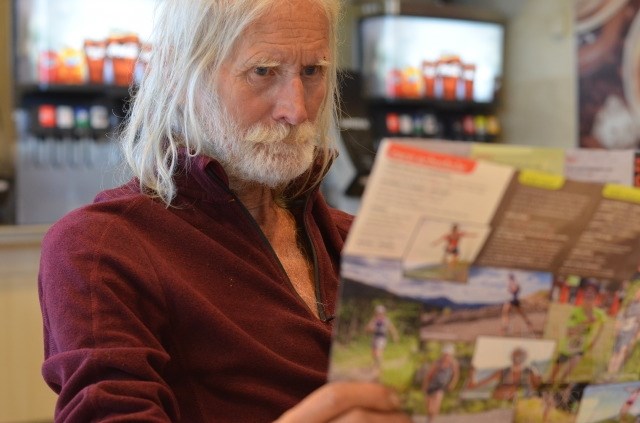

Dag checks out the latest Death Race brochure, which contains a picture of him.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON / iNFOnews.ca)

During the winter, Dag lives in a retrofitted school bus, but as soon as he can, he relocates to his camp in the woods. He’s been working on it for years, gradually carrying things up and building a network of trails where he can train without worrying about getting hit by a car — another real-life close-call he’s had. Eventually, he plans to live out there full time.

He subsists on a small pension, and without the typical drains of rent, cell phone bills and car payments, he “lives like a king”. His living room is a clearing in the woods, carpeted with pine needles and moss. His balcony is a cliff that overlooks the Okanagan Valley. His neighbours are bears, birds and deer.

“When people ask, ‘how are you doing?’ I say, ‘I’m the luckiest guy in the world. I have too much,’” he says.

WILDEST OF THE WILD

After a coffee and greasy breakfast at McDonald’s — a frequent calorie-stop for Dag — we drive north out of Vernon and park on the side of the highway. Eagles circle overhead and Dag mentions this is where road crews dump animal carcasses found on the highway. Indeed, we pass a heap of bones and skeletons as we ditch the car and start our ascent; we are at the end of Dag’s driveway and it’s a long one.

The hike takes us up old logging roads, through meadows, and over a creek where Dag collects water and washes his clothes. He tells me how sometimes, when he goes running at night, he can see eyes following him in the dark.

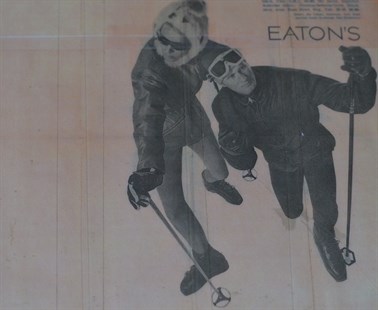

Dag modelling ski clothes in an Eaton's ad.

Image Credit: Newspaper clipping/ source unknown

“The animals are inquisitive,” Dag says. “If you show them respect, you never have a problem.”

Of all the wild creatures out here, I think Dag might be the wildest.

As a young man, he lived in the spotlight. In the 1960s, at a party in London (Dag was teaching skiing at the time in Britain) he caught the attention of a talent agent by pulling one of his many stunts: walking down a staircase on his hands. He was offered a job as a movie stuntman, and even landed a part in the James Bond movie Goldfinger with Sean Connery. Later, after finding his way to Whistler, he appeared in ski movies by filmmaker Jim Rice.

Aside from his infamous trip down The Lions, Dag was also known around Whistler as the guy who skied off rooftops, climbed out of gondolas to ride on top, and walked on his hands while still clipped into his skis.

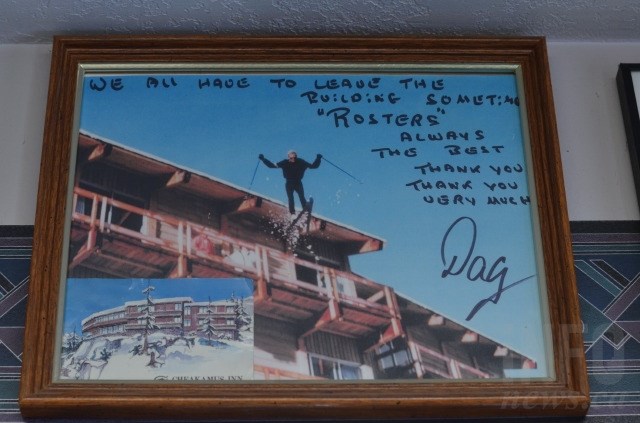

This photo of Dag hangs in the entranceway of Roster Sports Club Bar and Grill.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON / iNFOnews.ca)

He is, and will forever be, a celebrity and a legend. News articles over the years have dubbed him ‘the Father of Free Ride” and “The Last Ski Bum”. One newspaper article opens with: ‘Dag Aabye is 42 years of age going on 23.’ Another, written when Dag was 59, states: ‘Dag’s probably as fit as he was at 15.’ Through the years, the only thing that seems to change is the actual numbers; Dag continues to defy and ignore his age, constantly pushing the boundaries of what he’s capable of.

He never goes to the doctor, but why would he — he never gets sick. He trains every day for the gruelling, 24-hour-long Death Race, held annually on the August long weekend in Grande Cache, Alberta. He calls it "Doctor Death" and says it's the only check-up he needs.

“I refuse to become part of the age society where you do things based on your age. I keep pushing to see where my edge is,” he says.

ULTIMATE FREEDOM

After hiking about an hour-and-a-half up the mountain, Dag veers off the trail and holds back a curtain of evergreen boughs. There, in a sunlit clearing, is his camp. The tour consists of the kitchen (fire pit), bedroom (garden shed), and balcony (cliff overlooking the valley). He has enough books stored in rubber bins to fill a small library and has made his own homey touches to the clearing, like affixing a hook onto a stump for his coffee cup. He doesn’t own much. Among his most valuable possessions are old photos, newspaper clippings and birthday cards from his kids. He has three children, and immense pride fills his voice whenever he speaks of them.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON / iNFOnews.ca)

He doesn’t get lonely up on the mountain, says he’s too busy to. He’s up at 4:30 every morning and his days are filled with running, chopping firewood, reading and clearing his trails.

“It gives you an inner thoughtfulness,” he says. “You become a person that enjoys your own company.”

He eased into this simple life as one might relax into a pair of old boots.

In a way, he’s come full circle. Growing up on a farm in Sigdal, Norway, Dag’s parents often left him free to roam and spend the night by himself at a cabin near the home (they also kept him occupied as a toddler by sticking him on a pair of skis and leaving him alone. It wasn't long before he disappeared, already a natural and a daredevil. The next day, they put a rope on him.)

He loved the freedom as a child, just as he loves it now.

“One of the finest things in life, one of the most precious gifts we have is time itself. I see people wasting so much time. There’s a song… life flows like a river, and if you put something on it, it flows away. Because time never comes back. I wonder if people think that way.”

Not much gets Dag down. Every day is a good day, even the day his car was stolen at Silver Star years ago.

“I said ‘thank you Mr. Thief. You did me a favour. I never looked back,” Dag says.

He hasn’t owned a vehicle since. When he wants to go for a hike in Enderby or Kelowna, he just hops on the bus.

“My name for a car is an oversized wheelchair,” he says.

He hasn’t owned a television in many years, and the last movie he saw was Titanic (“horrible, horrible film,” he says.)

Instead of sitting in front of a screen, he’d rather read (a book has no commercials), run and be in the wild.

“My favourite is running down the mountain in the dark, and you run into the day. It’s like somebody opened the curtains and there is Vernon and the lakes and the city,” he says.

In Norwegian, Dag actually means ‘day’.

Dag at his camp.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON / iNFOnews.ca)

HIS LIFE, HIS WAY

As we come back down the mountain, the sound of the highway is like faraway static rising in volume. You don’t realize how loud it is in the city until you’ve been away for a while, Dag says. Sometimes, his ears ring for a while as they adjust.

His way of life may seem crazy to most, but the way some people live is crazy to him. He describes watching people drive around and around the Walmart parking lot, trying to find a spot just a little closer to the door, reluctant to walk a few extra steps. On his morning runs into town, he sees televisions flicker through windows, turned on as the sun rises. On the bus, he notices many passengers looking at their phones instead of out the window.

“People sitting there don’t seem to see the beauty anymore,” he says.

To him, that’s not living; it’s captivity.

After meeting one morning for coffee, I sit in my car and watch Dag walk off down the busy street. All he has with him is his backpack, stuffed with books. In that moment, I don’t know where he’s headed next, but his stride looks determined. Like the trail that leads to his camp, his path through life is a switchback of twists and turns. It's long and it's steep, but he built it that way, and only he knows where it leads.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON / iNFOnews.ca)

To contact a reporter for this story, email Charlotte Helston or call 250-309-5230 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2021