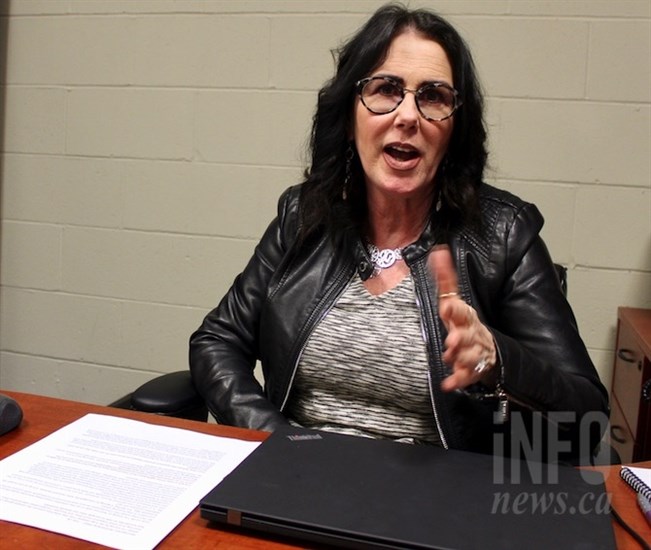

John Howard Society Executive Director Dawn Himer.

(ROB MUNRO / iNFOnews.ca)

March 04, 2019 - 8:00 PM

KELOWNA - Are all of the hundreds of homeless people hanging around Interior streets and filling emergency shelters qualified to live in the nice, new supportive housing units being built throughout the province?

The short answer is: yes.

While there may be a “rare” few who don’t want a helping hand, just getting to a shelter shows a determination to get off the streets, Dawn Himer, Executive Director of the John Howard Society of the Central and South Okanagan, told iNFOnews.ca.

Her organization manages two emergency shelters and half a dozen supportive housing complexes in Kelowna and will take on two more supportive housing buildings as soon as they can be built, likely before the end of the year. That's among dozens of new supportive housing projects throughout the Thompson-Okanagan and the province, all being operator by different partners.

“We basically want to get everybody into the queue for housing,” she said. “If they make it to a shelter, there’s usually a reason they’re interested in that (housing).”

The first step a person has to take is to fill out a fairly simple three-page application form. Basically, all they have to do is tick a box saying they’re in need. And there are lots of people around, like John Howard Society workers, who can help.

John Howard is only one of a number of agencies – including the RCMP – who keep an eye out for people on the streets and try to steer them towards services that can help them turn their lives around rather than end up in hospitals or jails. Or dead.

Yet there continues to be huge public opposition whenever B.C. Housing announces new supportive housing projects.

Such housing is a part of a concept adopted in many countries called Housing First. It’s aimed at getting the homeless into safe, secure housing as a first step to reintegrating into society because, as Himer points out, the vast majority of these people are not homeless by choice.

“I do believe we need to educate people on who our homeless folks are,” Himer said, noting that half of the homeless in Kelowna have been there for at least two years and used to have housing. “They still are part of our communities so we need to look at how we can work together. The more we understand, the less fear.”

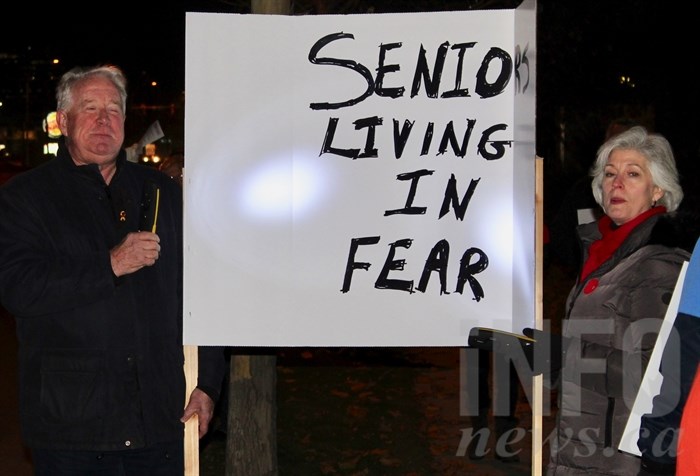

And, certainly there is fear, especially as expressed by opponents to the recent rezoning for the Agassiz project in Kelowna that city council unanimously supported following a seven-hour public hearing.

Protesters raised alarms when the Agassiz supportive housing project was proposed for Kelowna.

(ROB MUNRO / iNFOnews.ca)

WHO MAKES THE CUT FOR SUPPORTIVE HOUSING?

Part of that fear come from not knowing the process for selecting residents for the supportive housing projects and the fact that, as harm reduction facilities, residents are allowed to consume alcohol and drugs, just as people in any other apartment complex can do.

The selection process starts with filling out the application form, connecting with a social service agency and being interviewed to determine things like the state of a person’s mental health, addiction (or, as the agencies like to call it: “substance use disorder”) and other factors affecting their lives.

Then they wait.

When a new supportive housing project is ready for occupancy, it’s up to B.C. Housing to convene the Coordinated Access and Assessment Committee.

That includes representatives of B.C. Housing, John Howard (or whichever group is managing the facility), Interior Health, the RCMP and other agencies.

For Kelowna, there are about 500 people who are homeless or at the risk of being homeless on the waiting list for housing. A typical project has room for 40-50.

Since some rooms are designated for couples and others for people with disabilities, those are usually selected first. Then the list of single people is studied in detail with a goal of getting a “balanced mix” of people of different ages, genders and needs.

Given staffing levels of a minimum of two people on duty at all times, a facility can’t be filled with people who need close supervision. They can’t, for example, all have serious mental health or addiction issues.

“You do need a resident mix,” Himer said. “You don’t want everybody to be suffering from substance abuse disorder. It’s not a healthy environment for people to grow and move forward. So those who want to get well, they don’t want to be in a place where everybody is this way.”

Since John Howard has the job of managing the facility, it has the final say on who is going to live there.

“Tenants are chosen based on a structured and standardized assessment of their vulnerability and supportive needs, called the Vulnerability Assessment Tool,” Himer explained. “It ensures every individual at risk of, or experiencing, homelessness is thoroughly assessed and considered before an offer of housing is made.”

While there is a concerted effort to get all these people into the queue for housing, supportive housing isn’t for everyone. Some can’t function in such an environment so there is a need for smaller group homes. Just as there is a need for more affordable housing so the working poor don’t fall into homelessness.

“Sadly, many of the guests in our shelters have higher needs than can be offered in many of our current housing strategies and we are looking to innovative ways to support them,” Himer said, pointing out that Kelowna’s Journey Home Society is essential in trying to fill those gaps.

ARE THERE RULES ONCE PEOPLE MOVE IN?

Just being given an offer of housing isn’t enough.

Prospective tenants have to sign a Program Agreement that does put guidelines around how they behave.

“Some don’t like it,” Himer said. “They don’t, for example, like that their guest has to leave by 10 O’clock at night and they’re only allowed one guest.”

If they don’t want to sign the agreement, they don’t get the housing.

Once accepted, they have to sign in and sign out. Staff do room checks to make sure they’re okay and they can be evicted if they misbehave.

While eviction is rare, there was a recent case where a man in a Kamloops complex was kicked out after starting a fire in his garbage can.

Residents can be put on a Behavioral Contract for “anything that would pose a physical safety risk to someone else, whether that be residents, staff or the community,” Himer said.

IS DRUG USE RAMPANT?

The Housing First philosophy is that people need housing before they can deal with the issues in their lives that led to homelessness, which may mean dealing with addictions.

Himer says addiction is much more common in the general population than people realize, saying one in five suffer from addiction or mental health issues. That rate is higher in the homeless population but by no means is it universal.

Given that the general population is free to consume drugs and alcohol in their own homes, the same goes for supportive housing. It’s just that there are people around to help if someone wants to get clean or, if they are injecting drugs, someone is there to lessen the risk of overdosing.

One man at a recent open house for the proposed McIntosh supportive housing project, argued staff are condoning illegal drug use by allowing, for example, someone to smoke crack in the smoke pit.

Himer has some sympathy for that point of view but countered that, arresting someone for an illegal drug and sending them to jail is not really solving anything.

In fact, she said, studies show that the amount of alcohol people drink decreases once they have housing and, again, there are people around who can help them deal with their addictions and get treatment when they’re ready.

One man has already "graduated" from the Hearthstone supportive housing complex that opened in October in Kelowna.

(ROB MUNRO / iNFOnews.ca)

WILL PEOPLE STAY FOREVER?

Cardington Apartments, in downtown Kelowna, is one of the longest standing supportive housing facilities in the city, opening about 10 years ago.

There are some tenants who have lived there from the beginning but others have moved on.

And that can happen quickly.

One man who was housed in Heatherstone in October has already got a job and moved on.

One of the tasks Himer has set for herself is to compile statistics to track things like evictions and those who move on.

She’s also looking into city rules to see if she can increase the level of activities from things like the art classes, yoga and gardening to, possibly, bee keeping – activities that all help residents to grow and deal with the issues that put them on the streets in the first place.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2019