Lauren Marchand and her daughter at the head of Okanagan Lake in Syilx territory, where they often go to gather, play and be in ceremony.

Image Credit: Kelsie Kilawna

April 02, 2021 - 12:46 PM

When Lauren Marchand found out that an RCMP officer and a social worker had banged on her door, entered her home and searched it — without her knowledge or consent — she started crying.

“I just felt instantly violated,” says Marchand, who is Syilx from Inkumupulux (Head of the Lake) and a member of the Okanagan Indian Band (OKIB).

“My space was no longer sacred. It was no longer mine. It was no longer where I felt safe.”

It was Sept. 29, 2020 and COVID-19 cases in B.C. were on the rise again after a summer lull.

The police had received a tip from someone who alleged that Marchand was cooking methamphetamine in the home she shares with her daughter, who was five at the time.

They live in an affordable housing complex run by Vernon Native Housing Society (VNHS) in traditional Syilx territories in Vernon where Marchand works as an early childhood educator.

Jenny Duncan, a social worker with B.C.’s Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD), says the police asked the social worker to meet them at Marchand’s home. There had already been three “substantiated meth-related concerns” at the complex, according to her report, so “police and MCFD felt it was appropriate to act immediately.”

After getting a call from the police, Duncan reached out to OKIB and asked Jane Barren, a child and family advocate for the band, to join them.

The trio knocked on Marchand’s door. When no one answered, they entered and searched her home, finding no evidence of a meth lab. Then they left. Duncan didn’t tell Marchand they’d been in her home until nearly a month later — on Oct. 21.

The social worker has apologized to Marchand for not notifying her about the “intrusion” sooner, but Marchand says the issue is far from resolved.

She said that she wants it clearly documented in MCFD’s files that the social worker made a mistake and apologized for it. She wants assurance that if someone makes a malicious call about her in the future, the responding social worker will see evidence in her file of an excellent mother.

And she wants other parents to hear her story and know their rights.

Marchand’s history with the ministry

This wasn’t the first time social workers became involved in Marchand’s life. In early 2016, just after her first birthday, her daughter Brooklyn was diagnosed with leukemia.

The family had to move from the Okanagan to Vancouver so she could be cared for at the BC Children’s Hospital, says Marchand. For nearly three years they moved back and forth to the city, where Brooklyn received aggressive chemotherapy treatments.

Looking out over Komasket Park, Marchand holds daughter Brooklyn in the place where Inkumupulux chiefs are said to have trained.

Image Credit: Kelsie Kilawna

Meanwhile, Marchand says she was dealing with postpartum depression and anxiety.

“I felt I had lost my own identity at that time while staying in Vancouver. I was only referred to as ‘mom’ by nurses and doctors, I rarely heard my own name anymore,” she writes in a Facebook post published on March 11, 2021.

“I had to put myself last to be there for her with little to no opportunity for proper self care.”

At the same time, she says Brooklyn’s dad was navigating his own struggles.

“We were all in our own battles trying to survive down there together,” she says. “Eventually it was just me and my daughter. Her dad had left … It was mentally quite strenuous at that time.”

Wanting to go home to the Okanagan to get some counselling and “recharge,” Marchand asked her sister to step in.

Her sister had to stop working in order to care for Brooklyn, so they accessed financial support through MCFD’s Extended Family Program — which “provides support for situations when it’s best for a child or teen to live with a relative or close family friend when their parents are temporarily unable to care for them.”

While away from her daughter, Marchand says she video chatted with Brooklyn every day and cried for her every night.

In October 2016, after a couple months of focused self-care, Marchand says she returned to Vancouver to relieve her sister and resume full-time parenting. But social workers didn’t close her file, issuing a supervision order.

According to notes in Marchand’s file, social workers were concerned about her mental health, her “co-dependency issues,” and her on and off relationship with Brooklyn’s father, as they had concerns about his ability to parent.

Marchand describes feeling frustrated and scared at that time because the ministry’s involvement in her life had gone from voluntary to involuntary.

Finally, in June 2018, social workers closed her file.

“Lauren has addressed all MCFD’s concerns and is solely caring for her child Brooklyn. Lauren and [Brooklyn’s father] are no longer in a relationship,” they wrote. “There are no protection concerns regarding Lauren’s ability to care for Brooklyn … Case is now closed.”

‘A full-blown meth lab’

After her daughter’s extensive — and ultimately successful — chemotherapy treatments, Marchand and Brooklyn moved home to Syilx territory.

In short order, Marchand says she finished school, got her Early Childhood Education certificate and license, and secured a job at a daycare. In May 2020, she and Brooklyn moved into a housing complex managed by VNHS.

Fast forward several months to October — when, according to Marchand, the housing manager said a social worker had come around looking for her. Marchand says she called MCFD and left a couple messages before hearing back from social worker Jenny Duncan on Oct. 14.

“Apparently there was a report made on me that I was running a ‘full-blown meth lab,’ and that I was a drug lord. I’m not even going to lie, as soon as she told me that I burst out laughing,” Marchand says. “I don’t have the skill set!”

She arranged to meet with Duncan in person on Oct. 21, so they could clear things up. Jane Barren, the OKIB advocate, was invited to join them.

It was at this meeting that Marchand first learned that Duncan and an RCMP officer had been inside her home on Sept. 29.

Duncan told her that she and Barren had met the constable at the housing complex, and the building manager had given them a key to Marchand’s place.

Then, according to Duncan’s written documentation, the social worker “knocked three times” and called out Marchand’s name. When she didn’t get a response, the constable “banged very aggressively on the door.”

The constable then entered Marchand’s home, repeatedly calling out her name and announcing the police presence. Duncan later noted: “house is very clean, some toys laying out, a few dishes left out, no smells (mold, gas, drugs), no signs of drug paraphernalia, no bongs, lights, pipes, tin foil, needles.”

“Police were satisfied with the condition of the home and everyone left,” she wrote in her report. There was “no meth lab” in Marchand’s home and “no signs that [she] is unsafe.”

Duncan concluded that the call about the supposed meth lab was likely “malicious.”

Concerns for her daughter’s safety

When Marchand learned that the police had been in her home, she says she immediately thought of Brookyln.

Brooklyn dances among the buttercups, which signify to the Syilx People that spring has arrived.

Image Credit: Kelsie Kilawna

“My biggest concern with it … was how they came in,” she says. “Because my daughter had leukemia, her development is delayed — after all the treatments and everything.”

When Brooklyn hears people coming, she loves to jump out and “scare” them, she says.

“My fear is that if they come in my unit … and if she were to hop out, there’s armed officers that are preparing themselves to enter a meth lab … [and] a little girl who doesn’t have the capacity to understand what’s going on.”

These fears are heightened in the wake of Chantel Moore’s death, she says. Moore, a 26-year-old Indigenous woman was shot dead at her home in Edmunston, New Brunswick last June by a police officer during a so-called wellness check. Moore was a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation.

“I don’t want [Brooklyn] normalizing MCFD’s and RCMP’s presence in my life,” says Marchand.

“Especially after my history with MCFD, with them consistently telling me — while she was sick in the hospital — that they could take her from me, which was not something I needed to hear at the time, while I was watching her fight for her life.

“I just don’t want them anywhere near her anymore.”

She also bristles at the thought that her neighbours may have witnessed a police officer banging on her door and then entering her place, social worker in tow.

“Now you’re ruining my credibility within my own home,” she says. “I know there’s always this narrative of ‘Oh, MCFD’s involved with you. You must have done something wrong.’

“I didn’t do anything wrong,” she says. “You can be completely innocent, but be treated as a criminal.”

The healing circle

After learning her home had been searched, Marchand sought support from her chief and council, who helped arrange a healing circle. It was held at the ministry’s office in Vernon on Nov. 10, 2020, she says.

Marchand attended with her sister [IndigiNews reporter] Kelsie Kilawna, Barren, and Wanda Duncan, OKIB’s social development and community safety manager.

MCFD was represented by Duncan, her supervisor Scott Hladik, and Kemp Redl, director of operations for the North Okanagan.

During the meeting, Duncan apologized for not notifying Marchand sooner.

“It definitely wasn’t appropriate for me not to call you right away and explain that we had just entered your home without your permission or consent,” Duncan said during the meeting.

“I definitely took way too long to contact you and I apologize immensely for that. There are no excuses.”

She acknowledged that she “probably should have slowed things down a bit, and maybe called Lauren prior … to going into her house without her consent.”

Marchand said she appreciated everything that was said, and voiced her concerns.

“My biggest concern is that I was not notified,” she told the ministry workers, adding that she would have let them in because she’s an “open book” and “not a drug lord.” But she would have wanted to move her daughter to a safe place before allowing police into her home.

“If there are police officers even present, I do not want my child involved,” she said. “She’s very at risk for a lot of things.”

Kilawna told the ministry workers she thinks the police presence was unnecessary.

“Police involvement needs to be taken very seriously when it comes to Indigenous people,” she said. “The disproportionate rates of violence against us, against our family members, people that we love and care about who have been killed by police — this is so real.”

Marchand (left) and sister Kelsie Kilawna (right) often go the hills in Inkumupulux to gather, heal and engage in ceremony.

Image Credit: Kelsie Kilawna

Police had initiated the search, Duncan explained. They called MCFD and said, “We need a social worker. This is the report that we just got.

“We did not call them for back-up. They wanted us involved,” she said. “As soon as I got off the phone with the police, I called Jane [Barren].”

Under B.C.’s Child, Family and Community Services Act, “A police officer may, without a court order and by force if necessary, enter any premises … for the purpose of taking charge of a child … if the police officer has reasonable grounds to believe that the child’s health or safety is in immediate danger, and … no one is available to provide access.”

In cases where police suspect a child is at risk, they will immediately engage MCFD, says Chris Terleski, the spokesperson for Vernon North Okanagan RCMP, in an email to IndigiNews.

And “while social workers normally call parents in advance of a home visit,” according to an email from an MCFD spokesperson, “there are circumstances, such as reports that a child may be in immediate danger, when informing parents in advance would undermine a child protection investigation.”

Marchand told the ministry workers that she continues to be impacted by their intrusion. She said when she found out they’d been inside her home, she moved in with her sister for “probably a couple weeks.”

“I still don’t feel safe in my own home,” she said.

In B.C., Indigenous families are vastly overrepresented in the child welfare system. Due to the ongoing impacts of colonial policies and systemic racism, Indigenous children represent just over two thirds of all kids in care in B.C., despite the fact that Indigenous kids only account for about 10 per cent of the total population of kids under 14 in the province.

Marchand pointed to this systemic discrimination during the meeting, explaining that Brooklyn’s relatives, on both sides of her family, have been taken from their parents through residential schools, day schools and the Sixties Scoop.

Six-year-old Brooklyn is being raised to love the land and create a kinship of belonging with the timxw (spirit of the land).

Image Credit: Kelsie Kilawna

“We are in the Millennial Scoop right now with MCFD,” she said. “And the fact that I have to sit here today and even accept an apology is infuriating.”

After the meeting, Marchand and Barren chatted outside the building. Barren said she didn’t tell her about the home search because Duncan said she wanted to tell Marchand in a face-to-face meeting. She said she followed up with the social worker multiple times.

“I was like, ‘Hey, what’s going on with Lauren? … Have you reached out to her?’ And she was like, ‘No, I’ve been super busy. I’m going to do it soon. I’m really sorry.’”

“That is so wrong,” says Chief Byron Louis of the Okanagan Indian Band, over the phone. “Not having the common courtesy to report that immediately.”

Not only was Marchand’s “reputation just dragged through the mud,” but “incidents like these can have some really life-altering results,” he says, pointing to Chantel Moore’s death.

“There needs to be an understanding that this is very serious,” he says. “They have to understand the powers they have over families, especially over single parents.”

When contacted, Duncan said she couldn’t comment and suggested getting in touch with MCFD’s spokesperson.

Why did VNHS give them a key?

Karen Gerein is the executive director for VNHS. She didn’t find out about the search until after it happened, and she says she “just couldn’t believe it” when she heard police had searched Marchand’s home for evidence of a meth lab.

“She seems like a complete sweetheart. We’ve had no concerns about her whatsoever,” she says over the phone.

Gerein says this was the first time a VNHS staff member has been asked by police or a social worker for a key to a resident’s home. The housing manager was pretty new to the job, she says, and he assumed the social worker, constable and OKIB advocate had legal right of entry.

Gerein feels they could have “checked things a bit more” and consulted with VNHS staff before entering Marchand’s home. In her view, this wasn’t a case of clear and immediate danger to the child.

“Everybody knows that for generations there have been a disproportionate amount of child apprehensions in Indigenous families, compared to non-Indigenous families. In this age and stage, with recognizing reconciliation, I’m surprised that an incident like this would happen.”

She says that VNHS is now drafting a policy around right of entry for MCFD and RCMP, which acknowledges tenants’ right to privacy.

“The society has an obligation to protect the lawful right of its tenants and it takes this obligation seriously. It also acknowledges that MCFD and RCMP have rights of entry through the courts and will now require that proof be shown prior to any admittance,” she writes in an email.

In other words, “if you don’t have a legal right, if you don’t have a court document, we won’t permit access,” she says.

Clearing her name

During the healing circle on Nov. 10, Marchand and her supporters said they wanted Duncan to document exactly what happened — including her wrongdoings — in Marchand’s file.

Duncan assured her that she’d done this.

“It is clearly documented in there that this was a malicious report. There’s obviously no protection concerns at all, and my lack of getting a hold of you was my fault. And that we had gone in with police without your consent,” Duncan said.

Marchand couldn’t verify this at the time because she hadn’t yet received MCFD’s records about her, which she’d requested through a Freedom of Information request. She’s since received the file, and she’s concerned about the story it tells.

She doesn’t see a story about a strong, loving mother who has fought through adversity, supporting her baby through cancer treatments while prioritizing her own mental health — she sees protection concerns.

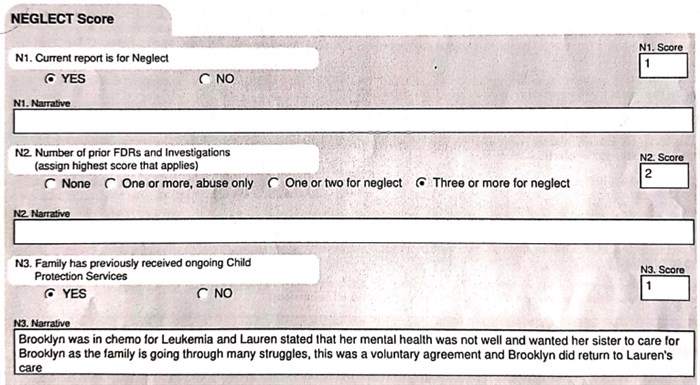

She sees that she was ranked as a “moderate” risk in a vulnerability assessment, dated Oct. 21, 2020 — which was the day she first met Duncan and learned they had searched her home. In these assessments, social workers use a point system to determine a parent’s neglect and abuse scores.

“Vulnerability assessments are one of several decision-making tools [social workers] use to determine whether a child or youth might be in need of protection,” writes an MCFD spokesperson in an email.

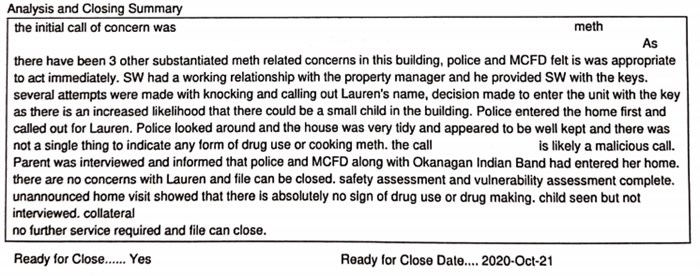

Part of a vulnerability assessment completed by an MCFD social worker and dated Oct. 21, 2020.

Image Credit: Brielle Morgan

Marchand was given five out of a possible 14 points in the neglect category. She received one point for the “current report” — i.e. the unfounded call about the meth lab. She was also given a neglect point for her previous involvement with the ministry.

The social worker offers context for the latter point: “Brooklyn was in chemo for Leukemia and Lauren stated that her mental health was not well and wanted her sister to care for Brooklyn as the family is going through many struggles, this was a voluntary agreement and Brooklyn did return to Lauren’s care.”

In Marchand’s view, these points are unwarranted. She believes seeking support as a single parent when your baby is fighting cancer is a sign of a strong, responsible parent — not a neglectful one. And she wants her file to reflect this.

“It’s just disturbing to know that this is going to land on a social worker’s desk,” she says.

Marchand sits in a place sacred to the Inkumupulux while her daughter runs around, picking buttercups.

Image Credit: Kelsie Kilawna

“They really vilified my mental health. They made it seem like I’m completely unable and inadequate as a parent because of it. And I was misdiagnosed, too,” she says. “My psychiatrist said I had a bunch of things, which I didn’t. It was just my anxiety, my postpartum under so much stress … appearing to be another diagnosis.”

“I’m off all of my medications now. I weaned myself off. I found what works. I know my triggers and everything,” she says. “Brooklyn’s father and I have a healthy co-parenting relationship … To me, he’s very much valuable in her life.”

But these finer points aren’t detailed in the social worker’s closing summary, and neither are the milestones Marchand achieved when she and Brooklyn returned to Syilx territory — how she finished school, got her ECE, secured a job and a home.

Marchand doesn’t see herself reflected in the ministry’s file. She also sees a lack of accountability on MCFD’s part.

In MCFD’s incident report, the Sept. 29 intrusion is described as an “unannounced home visit,” but the report doesn’t explicitly state that Duncan did not call Marchand before going to her house with the police. And nowhere does it say that she failed to notify Marchand about the intrusion until nearly a month later.

Part of an incident report written by an MCFD social worker and dated Oct. 21, 2020.

Image Credit: Brielle Morgan

“She promised that she would make it very clear of her wrongdoing in all of this … and there’s no word of it,” says Marchand.

In the healing circle, Kemp Redl, MCFD’s director of operations for North Okanagan, said some people like to “write their own statement and have that added to the file,” and she could do that if she likes.

Marchand says she definitely wants her version of events on file, and she plans to submit a statement.

“We’re spending a ton of time and energy trying to learn more about how to work with Indigenous families in a better way,” Kemp added. “We have a lot of room to grow still.”

‘I don’t feel safe’

As a result of this experience, Marchand says she’s noticed herself moving closer to her traditions.

“I don’t trust these systems to be in my benefit. I haven’t for a long time, but now it’s just, like, nail in the coffin,” she says.

“I truly don’t believe that I’m safe at all. I don’t feel safe calling the police. I would never feel safe calling the ministry for anything anymore. Unfortunately it came to a point where I was questioning my band, too, but fortunately that was dealt with very quickly.”

Marchand braids her daughter’s hair, a traditional practice used to connect people’s spirits or to feel grounded.

Image Credit: Kelsie Kilawna

These systems need to be rebuilt from the ground up, she says. In the meantime, ceremony and community are helping her to heal, and to grow as a parent.

“I am forever grateful for the amount of support and help we have received at our most trying of times and our best of times,” she writes on Facebook. “The biggest shoutout to Brooklyn for being the strongest little warrior I know, my biggest inspiration, my best friend and my littlest love.”

— This story was originally published by The Discourse and IndigiNews.

News from © iNFOnews, 2021