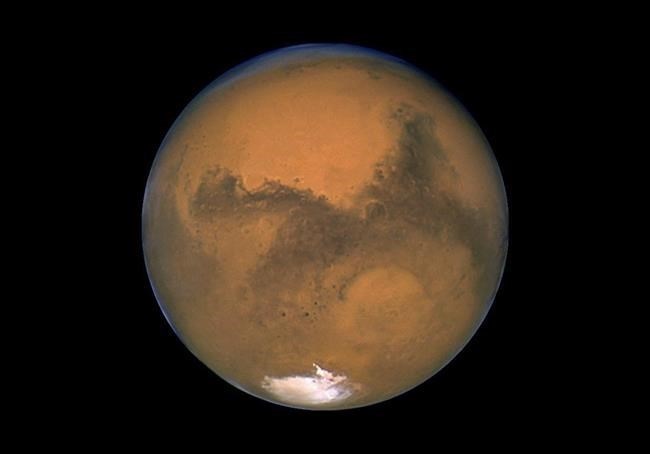

This Aug. 26, 2003 image made available by NASA shows Mars photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope on the planet's closest approach to Earth in 60,000 years. Research is debunking old theories about how Mars got its moons. Chris Herd, co-author of a newly published paper, says scientists used to believe that Deimos and Phobos were once asteroids.

Image Credit: THE CANADIAN PRESS/AP, NASA

October 04, 2018 - 8:00 PM

EDMONTON - New research suggests Mars' moons were once part of the planet, blasted into space by some cataclysmic collision long ago.

Until now, the most common theory was that Deimos and Phobos were once asteroids, captured into orbit by Mars' gravitational field.

"They kind of look like asteroids," said Chris Herd, a planetary geologist at the University of Alberta and a co-author of a new paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

"They're really pockmarked with craters and they have those characteristics that make them look like asteroids we've seen farther out."

Still, doubts remained — especially since the red planet's two moons are so black.

"Those objects are really dark," Herd said.

"They absorb most of the light, with the exception of a few per cent of the sunlight that comes in. That means the information you have for figuring what they're made of is limited."

Herd and his colleagues took a new approach.

They analyzed light recorded from one of the moons by the Mars Global Surveyor mission that orbited the planet in 1997. They then compared that analysis with a similar look at a meteorite known to have come from the asteroid belt — the Tagish Lake meteorite from northwestern British Columbia.

They didn't look like each other at all.

"It was not a match," said Herd. "The best match is ground-up basalt, the kind of common rock that Mars is made of."

The most likely conclusion is that Deimos and Phobos are chunks of rock blown off the surface of the planet, perhaps by a collision with some other heavenly body far back in the history of the solar system.

The theory may help to explain another puzzling feature of a planet that has fascinated skywatchers for centuries.

Mars' northern hemisphere has a far lower elevation than its southern half. The difference is large — several kilometres.

"We don't really know why that is," said Herd. "It's a pretty fundamental problem in Mars science."

Scientists have long wondered if the difference is the result of some long-ago impact.

"There'd be lots of debris that came off of that. If that was the case, then you you'd probably end up producing a whole bunch of objects in orbit around Mars and Phobos and Deimos are the ones that are left."

— Follow Bob Weber on Twitter at @row1960

News from © The Canadian Press, 2018