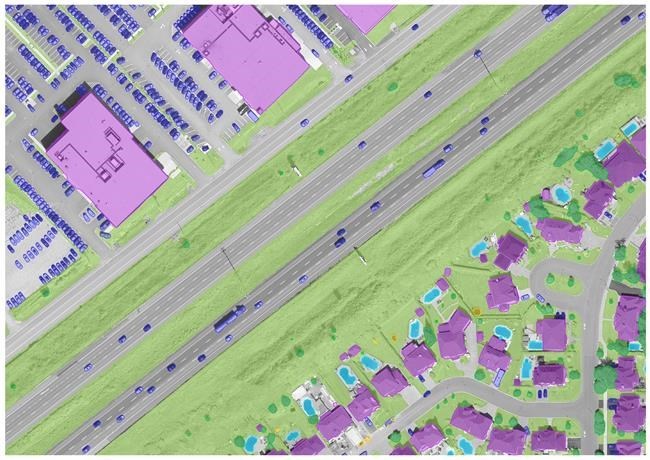

Municipalities in Quebec’s capital region have recently begun using artificial intelligence to track everything from tree cover to cars -- and even backyard pools. The Communauté métropolitaine de Québec says the data can help municipalities achieve their environmental targets, monitor urban development and even assess parking availability. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO-Communauté métropolitaine de Québec *MANDATORY CREDIT *

July 28, 2024 - 3:00 AM

MONTREAL - Municipalities in Quebec’s capital region have recently begun using artificial intelligence to track everything from tree cover to cars -- and even backyard pools.

The Communauté métropolitaine de Québec, which groups Quebec City and its suburbs, says the groundbreaking project will help member municipalities achieve their environmental targets, assess parking availability and monitor urban development. But as more Canadian cities adopt AI tools, experts warn they need to think carefully about how they’re using the technology, and whether the public is fully on board.

Frédérick Lafrance, geomatics development manager at CMQuébec, said the organization has trained a deep learning model on high-definition aerial photos of Quebec City and the surrounding region taken in 2021. The AI model can pick out and highlight several different features, including buildings, trees, vehicles, swimming pools, backyard trampolines and jungle gyms.

“The performance is equivalent or very similar to a human,” he said in a recent interview. “Except that the speed of execution is much greater, so we can do a lot of work in very little time."

The data can be used in different ways. Lafrance said Quebec City and many surrounding municipalities have targets for urban greening and tree cover, and artificial intelligence is a natural tool to measure progress. Conversely, it can also measure how much green space has been converted to asphalt over time.

Municipalities could also use the images to see whether there’s enough parking in different areas, he said. And tracking backyard pools could help cities decide where to send inspectors.

“That information is difficult to obtain because it requires a lot of manual labour,” he said. “So we’re offering a service that shows them where the pools are, and they can use that to follow up.”

A new set of aerial photos is being taken this summer, Lafrance said, and he hopes to analyze them this winter. He’s also hoping to apply the technology to photos taken as far back as the mid-20th century to assess how the region has developed over time. The 2021 images are currently available through the provincial government’s open data portal.

Lafrance said he believes CMQuébec is the first municipal body in Quebec to use AI in this way, though he thinks it’s only a matter of time before other big cities adopt similar tools.

Renee Sieber, an associate professor of geography at McGill University who studies artificial intelligence, said municipalities across the country are already using AI in a range of ways.

Edmonton, for example, has used artificial intelligence as part of a project that uses remote cameras to monitor wildlife entering the city. Montreal and Toronto have experimented with AI to reduce traffic congestion, and Montreal’s transit agency is working on a pilot project to use AI to prevent suicide in the city’s subway system by scanning CCTV footage for signs that someone is in distress.

Still, Sieber cautioned that some applications of AI raise more concerns than others.

“There’s a big difference between a tree and a backyard swimming pool,” she said, adding that cities can use such technology to help find minor violations – pools without fences, for example, or illegal sheds in people’s backyards.

“I'm always wary of cities that don't have clearly identified objectives … because that increases the potential for mission creep,” she said. “Frankly, people don’t like to be surveilled from above, and it’s very different from having a building inspector walk around and peek into someone's backyard …. It creeps people out.”

In the case of Quebec City, Lafrance pointed out, the aerial images already exist, and the AI isn’t revealing information that couldn’t already be tracked manually – it would just be much slower. The image resolution is sharp enough to differentiate between a car, an SUV and a truck, for example, but not to identify the make and model of individual cars, let alone licence plate numbers.

There are wide-ranging possibilities for municipalities that want to make use of artificial intelligence applied to images. Google has used a combination of aerial images and AI to estimate tree cover in hundreds of cities around the world, including Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.

Richard Khoury, a computer science professor at Université Laval, said the Quebec data could be used to assess the value of different properties and to target less-developed areas for urban development projects.

But AI has the potential to reveal more than just the number of trees and cars in a neighbourhood.

A 2017 U.S. study used deep learning to identify the make and model of cars in 50 million images from Google Street View. The researchers found that cities where sedans outnumbered pickup trucks had an 88 per cent chance of voting Democrat, while cities with more pickups than sedans had an 82 per cent chance of voting Republican.

The authors presented their findings as a powerful tool for researchers and policymakers, but also pointed to important ethical questions. “It is clear that public data should not be used to compromise reasonable privacy expectations of individual citizens, and this will be a central concern moving forward,” they wrote.

Sieber said municipalities need to think about how the public will respond to their use of artificial intelligence. “No tool is neutral,” she said. “When you talk about trustworthiness in AI, there’s an issue of performance … but there’s also an issue of social acceptance. If you’re invisibly surveilling people, you’re not increasing social acceptance, probably.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sunday, July 28, 2024.

News from © The Canadian Press, 2024