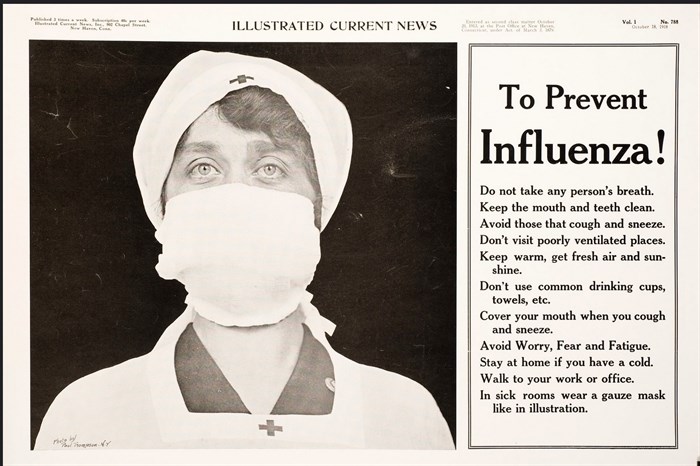

New Haven, Conn. Illustrated Current News, 1918. Image.

Image Credit: National Library of Medicine

April 19, 2020 - 12:00 PM

Close churches, schools, libraries and theatres. No more public weddings or funerals. Loitering in restaurants and bars is prohibited. Avoid crowded areas.

Those orders were made throughout the Okanagan a month ago, along with nearly every other Canadian city, by officials aiming to stop the spread of COVID-19.

It’s unlike anything in living memory, but it’s certainly not unprecedented.

The same orders were made in November 1918, when the Spanish Flu had creeped across Canada, slowly but surely finding its way to Kelowna.

“It was just as they were signing the Armistice — the Great War was coming to an end and a second war was just starting,” Bob Hayes, a local historian who extensively researched the pandemic that swept across the globe 100 years ago.

Kelowna had two weekly newspapers in 1918, and they both came out on Thursdays. Each week they tracked the movement of the flu across Canada, Hayes said, much the same way news organizations have been tracing COVID-19’s moments across the globe.

“They reported it was in Winnipeg then, two weeks later, it was in the Okanagan,” he said. “And they were prepared for it when it came — they were on top of it.”

Spanish Flu ad in Kelowna newspaper, November 1918.

Image Credit: Facebook/Old Kelowna

A notice was issued in the local papers, outlining the measures that would be taken.

“They were to close schools, churches, there were no more meetings — they were really on top of it,” Hayes said.

Then as now, isolation was seen as the best preventative measure. The biggest difference was then the Okanagan was more sparsely populated, so self isolation was less of a struggle.

“They had struck a medical board and Dr. Knox was the medical health officer and they were having meetings on what to do and taking in submissions,” Hayes said.

Among the suggestions, Len Hayman, one of the captains on the ferry boats that moved people and supplies up and down the valley at the time, suggested that at the docking point, where Kelowna’s signature Sails sculpture is now, there would be a tent where people would be sanitized before they came ashore.

“I don’t know if it was used, but they took it and gave it to the medical board,” Hayes said.

At the very least, it was clear they were taking things seriously and the papers responded with some self-congratulatory editorials.

“They were saying ‘we did well and we dodged a bullet,’” Hayes said, reflecting on the articles he read from the time. “From Oyama in the north to Peachland in the south, (they) could only find one Caucasian who died of the flu — Eileen Clements. While they were congratulating themselves, however, they didn’t realize two streets over in Chinatown, things weren’t going well.”

The Spanish flu may have skipped over those who had lived in acreages around the town centre, but in the week following those triumphant articles, Leon Avenue — roughly where the Gospel Mission is now — was hit hard.

It was Kelowna’s Chinatown and nine Chinese men, a Japanese man and an Indo-Canadian man who were all living in close quarters, died.

“It hit a specific population, the Chinese population in Kelowna was a very male population,“ he said. “It was quite congested, building next to building next to building. And the sanitary conditions weren’t great, they didn’t have sewers.”

While Hayes stresses that he’s not a scientist, and doesn’t know for sure why the virus spread to that neighbourhood, he said that the timing does match the travel patterns of its residents.

In November, a lot of the Chinese men were leaving the countryside farms they’d worked on throughout the spring and into the harvest. Then they returned to the boarding houses on Leon Avenue.

Once the flu reached Leon, where there had been little awareness of the unseen threat, it spread fast.

The larger community then sealed off Chinatown and everyone else went into lockdown.

“You could not get in and out,” Hayes said.

While few tread in the area that had been locked down, Archdeacon Thomas Greene, the top guy in the Anglican Church, entered the area knowing he wouldn’t be able to leave until the virus had worked its way through.

Years later, when he was a much older man, the Chinese community honoured him for the risk he took.

“The rest of the world said 'you’re on your own', but when they said ‘we need help,’ he went there,” Hayes said. “That stands out as an example of the compassion people show.”

There were plenty of examples in local papers of the less than welcoming stance many took.

By Christmas that year, though, everything had settled and life eventually settled back into a new normal and Hayes thinks there are lessons to be taken from the time.

“The council of the day had full marks for being prepared,” he said. “Closing down was very effective in the day. And they knew about isolating and tracking it. That’s what we’ve done again.”

He also pointed out the populations that are often left behind — the homeless and poor— shouldn’t be forgotten while everyone else isolated. Their conditions may give way for higher risk conditions now, as they did then.

The Spanish Flu struck Canada hard between 1918 and 1920. The international pandemic killed approximately 55,000 people in Canada, most of whom were young adults between the ages of 20 and 40.

According to Parks Canada, the deaths compounded the impact of the more than 60,000 Canadians killed in service during the First World War (1914-18). Inadequate quarantine measures, powerlessness against the illness, and a lack of coordinated efforts from health authorities led to unsurmountable chaos.

It came in multiple waves.

Parks Canada said the first wave took place in the spring of 1918, then in the fall of 1918, a mutation of the influenza virus produced an extremely contagious, virulent, and deadly form of the disease. This second wave caused 90 per cent of the deaths that occurred during the pandemic. Subsequent waves took place in the spring of 1919 and the spring of 1920.

The deaths, estimated at between 50 and 100 million, claimed the lives of somewhere between 2.5 and five per cent of the global population. Most of the victims were in the prime of their lives.

In Canada, the disease arrived at the port cities of Québec City, Montréal, and Halifax, then spread westward across the country.

"Criticized for failing to provide resources and coordination to public health authorities across the country, the federal government responded to the crisis by founding the Department of Health in 1919," Parks Canada said. "From then on, public health was a responsibility shared by all levels of government."

To contact a reporter for this story, email Kathy Michaels or call 250-718-0428 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2020