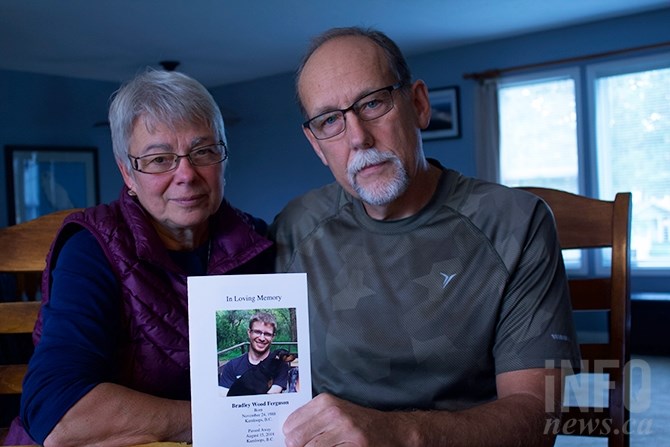

Lynnette (left) and Mike Ferguson hold a program from their son Brad's memorial service. Brad died from suspected complications of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome on Aug. 15, 2018.

(ASHLEY LEGASSIC / iNFOnews.ca)

September 18, 2018 - 7:30 PM

'HE'D HAVE TO WAIT SOMETIMES FOR SIX, SEVEN HOURS UNTIL THEY COULD GIVE HIM THE HYDRATION... EIGHT HOURS OF WAITING."

KAMLOOPS - Brad Ferguson loved life, family, gaming and reading. These are the characteristics Lynnette and Mike Ferguson will hold close to them after their son's sudden and unexpected death last month.

Lynnette and Mike believe Brad didn't need to die from a rare syndrome that severely impacted his life over the past eight years, and now they're fighting to make sure his story is heard and remembered.

Brad was 29 years old when he died on Aug. 15, and although there's no official cause of death yet, his parents believe he died from complications of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome, or CVS. It's rare — only affecting roughly two per cent of the population in North America, but as Mike points out, that number only covers confirmed cases.

"Two per cent of the population have it, but those are the ones diagnosed with it, right?" Mike says. "So how many other people have it that are undiagnosed?"

CVS is as bad as it sounds. For some people it can be debilitating, days-long episodes of violent vomiting, while others may have a couple of episodes every year. But for Brad, the syndrome was severe. He had to go from full-time to part-time work, and even then it was a struggle to make it through his shifts.

"The irony of this is the CVS robbed this young man of any future, like he was an honour student in high school. In fact he wrote some university papers for his brother and his friends in university," Mike laughs. "We figured he'd just breeze through his undergrad and be out in the world, but that robbed him of any education because he'd be sick for a week, it'd take him a week to recover. He would have maybe two weeks of being OK, and then he would start over again. It’s just the way this disease presents itself, it's just ugly."

"I can remember one time going down and oh, it’s not just a normal puking," Lynnette says through tears. "It’s a gut-wrenching, awful, awful sound, and no one could do anything about it and he’d have to just keep doing it until he could somehow calm himself."

The Ferguson family feels robbed of Brad's presence and bright personality. They recall some of his strongest and most stubborn moments while sitting at their dining room table in their Upper Sahali home. The table is covered with photographs of Brad, including a picture of his tattoo of the family tree with the names of his immediate family on each branch.

As rare as CVS is, the deaths related to complications of the syndrome are rarer still. Debbie Conklyn, program director for the Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Association, says numbers aren't available.

"CVS itself is not truly life-threatening," Conklyn says. "It’s more the complications of what happens when your body is going through an episode."

She says for some people the vomiting can go on for days.

"That’s just not good for your body to go on and on and on vomiting and not getting proper nutrition and not getting enough fluids," Conklyn says. "There isn’t one pill that you can give to everyone and say 'take this it'll make you feel better'. There is no cure, there is no procedure that will fix it, and there is no medication that is labelled for CVS."

The persistent vomiting that comes with CVS can lead to severe dehydration, lack of nutrients and even organ failure.

The Fergusons say the coroner suspects dehydration may have caused Brad's heart to stop the afternoon of Aug. 15. Mike remembers that day. He spoke with Brad around noon, offered to take him to the hospital during one of his episodes. Brad declined and instead tried to hydrate himself at home and sleep it off. He told his father his friend would take him to the hospital later on, but when the friend went to check on him later that day, Brad was dead.

"We have lots of what we 'could have' and 'should have done' feelings and that's very difficult to deal with," Lynnette says. "That's something that we have to come to terms with... He wanted to live. He had two little nieces and a son. There was a lot to live for. He loved life, and it was taken."

CVS was something Brad dealt with since he was around 20 years old, although he didn't get a formal diagnosis until roughly a year and a half ago, when he made a trip to Phoenix for college basketball's March Madness tournament, something he was extremely excited about.

But his family says stress of any kind was a trigger for Brad's CVS and he ended up in the hospital during the family trip. Although he was disappointed he couldn't attend the basketball games, his family says it was a relief to finally have some answers for their son's condition.

"So off we go in Phoenix to the hospital and had an initial diagnosis of undiagnosed type I diabetes... which was not good on one hand but very good on the other hand because you can live with diabetes," Lynnette says. "They did all sorts of tests on his abdomen, and scans and blood work, and in the end the doctors concluded it was cyclic vomiting syndrome so that's where he got his official diagnosis."

There's no set treatment for CVS, but a combination of things can help mitigate symptoms for different patients.

For Brad, he focused on his diet and taking some anti-nausea medication. His aunt, Verita van Diemen, says there was a nearly two-month period this past spring when Brad finally felt that he might be turning a corner.

"He was so optimistic and then an episode hit," Verita says. "It absolutely devastated him because he thought they were on to something."

All throughout Brad's bouts of illness there were peaks and valleys. There were only a handful of times when he felt like he may be turning a corner with his CVS, but they gave him hope.

"But it could carry on for two, three days, which for most of us we can’t even fathom," Lynnette says. "So that was his life, and then if it got so bad he’d go into (the emergency room) and get rehydrated, and then the cycle would start again. He’d recover enough and go back to work, feel pretty good for two, three, four weeks sometimes, and then it would start over."

Mike and Lynnette believe if Brad could have been streamlined to get immediate hydration for his illness during an episode, he may have been more willing to go to the emergency room the day he died. Now, they're fighting to make that streamlining a reality through the Royal Inland Hospital Foundation. They've spoken to the foundation regarding setting up a 'hydration station' within the hospital.

"There could be a hydration station, somewhere in a corner with just a few chairs. Brad said we don’t have to have a bed, just sit there in a chair and and let the hydration happen because it takes like two to three hours for the hydration," Lynnette says. "(Making) that a streamline process — that would be heaven-sent from my perspective because then Brad himself would not have been reluctant to go to (emergency). He would have said 'yes, I'm in there' and we know that."

As Lynnette points out, the intravenous hydration station wouldn't be just for CVS patients, but diabetics, cancer patients, and anyone else who has an illness that requires an IV to rehydrate. Mike explains that ketoacidosis, which can occur in CVS or diabetes patients, is a state where severe dehydration can cause issues with the body's organs.

"Ketoacidosis can kill you," Mike says. "When you reach that state, hydration is only through IV. If you reach a point where you could not hydrate yourself.... If the heart is short of the potassium in your system, you’ll die from a heart attack."

Immediate treatment is necessary when a CVS patient is going through a severe episode, and the sooner someone is hydrated, the sooner their episode will end. That can be difficult when the only emergency treatment option for CVS patients is going to the hospital, where patients are triaged based on risk. Sometimes Brad would have to wait hours to get the hydration he needed which is why a hydration station is an important piece of the puzzle for the Fergusons.

"He'd have to wait sometimes for six (or) seven hours until they could give him the hydration," Mike says. "So it became a struggle... there were times that he would go in and it would be eight hours. I mean eight hours of waiting."

Not only do patients sometimes have to wait hours on end to receive their IV treatment, but CVS patients can also be violently ill while waiting to be seen by a doctor. Lynnette says the idea of the hydration station would also provide patients with some privacy so they didn't have to be sick in front of so many other people.

The Fergusons are also working with the hospital foundation to bring more awareness and education to healthcare staff regarding CVS, including potentially introducing an explanatory video by a doctor specializing in the syndrome which describes the best protocol when treating a CVS patient. Lynnette says the video would be accessible by healthcare professionals across the Interior Health Authority.

"We've been so overwhelmed actually, at the people who have donated to Brad's memory in terms of helping with this whole ordeal," Lynnette says.

As the Fergusons move forward in their life without Brad, they'll hold onto the nearly three decades of memories he gave to them, and remember him at his best instead of his worst.

"Lots of laughter, and had a great sense of humor," Lynnette says. "His friends reiterate that to us over and over."

To contact a reporter for this story, email Ashley Legassic or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2018