Image Credit: Shutterstock

March 28, 2021 - 7:30 AM

Experts won't even guess how many are here, and no one is entirely sure how they got here in the first place – but one thing we do know is that the Okanagan is infested with rats.

"The Okanagan Valley is an ideal home for rats, there's tons to eat, there's plenty of water, there's a lot of places for harbourage," Bug Master Pest Control owner Steve Ball told iNFOnews.ca. "For the last couple of years it's gotten out of hand."

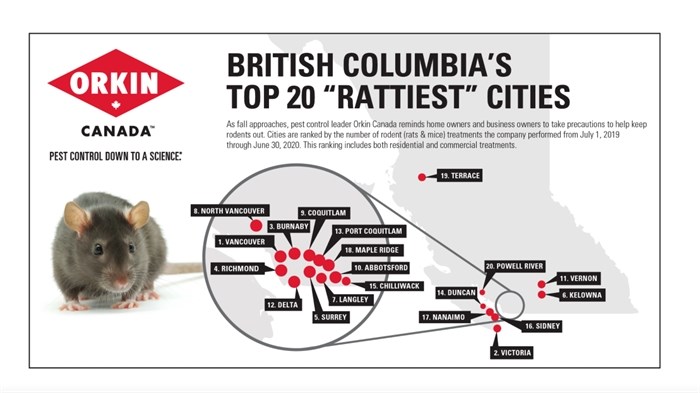

Ball said his Kelowna-based company started getting calls about rats seven or eight years ago. Complaints about rats started coming in from Osoyoos, then Oliver, then Penticton, and eventually Kelowna. It's now well documented that rats are established as far north as the Shuswap. There are also in the Kamloops area and have made their way to the Kootenays. There are two types of rats in B.C., the Norway rat and the roof rat, and last fall Kelowna was ranked the sixth rattiest city out of 20 in B.C., while Vernon came in at 11th place by pest control company ORKIN Canada.

And while nobody wants rats, opinions are divided on how to get rid of them.

The City of Salmon Arm is the latest municipality to ban the use of second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides, better known as industrial strength rat poison.

Salmon Arm voted unanimously March 8 in favour of the ban and is the first city outside the Lower Mainland and Greater Victoria to add its name to a list of more than a dozen municipalities that have banned rodenticides on city-owned property.

It's a move applauded by the B.C. SPCA.

"It's huge for municipalities to make this change, it's the first time we've seen real progress on this issue and we've been raising it for many years," B.C. SPCA scientific officer Sara Dubois said.

Dubois says the change has come about following several high-profile cases of raptors being killed after eating rats poisoned with rodenticides.

Pest control companies will plant rodenticides in traps outside in problem areas, but after eating the poison the rats can take a few days to die. In this time period, the rats can be snapped up by birds of prey and other animals, which then ultimately end up being poisoned themselves.

READ MORE: You dirty rat: The vermin have spread to the Shuswap

While some municipalities in B.C. have recently got on board, Dubois says the problem isn't new and has been going on for decades.

"So many are never found, these animals are going off into the bush and dying... it's rare that we find an animal that has died and we can send it off for testing," she said.

Dubois said there is no disputing that rats need to be dealt with, but poisoning is not the answer.

"If animals need to be killed for health and safety reasons there are ways to do it that are quick and fast," she said.

New Zealand company Goodnature has developed a captive bolt trap powered with a carbon dioxide canister. The rat goes up a tube that triggers a sensor that hits it with a bolt. The blunt force trauma causes instant death.

Dubois said a UBC team is currently doing research into their use in North Vancouver, and studies are going on elsewhere in the Lower Mainland.

While anticoagulant rodenticides have been banned in multiple municipalities, the ban only applies to city-owned property because the local governments don’t have the power to outlaw the chemicals on private property. Any change in the law which extends to private property would have to come from the province.

And the fact that rats don’t distinguish between public and private property was made very clear last fall.

Last October in Saanich, a well-known great-horned owl called ‘Ollie' was the third owl believed to have died after ingesting rat poison in three months, although the District of Saanich had banned rodenticides earlier in July following the publicized deaths of other owls.

Ultimately, change needs to come from the province.

"They know it’s an issue but those dead bodies of owls haven’t been stacked up in front of them," Dubois said. “The long-term goal is to completely ban rodenticides in British Columbia."

And according to the province, it is looking into the issue.

"My ministry is looking at a range of actions that may be taken to prevent these poisonings including public engagement, education, training, and also whether these products need to be more strongly regulated," B.C. Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy George Heyman said in an emailed statement. "We are also engaging with other provincial, federal and territorial jurisdictions to understand how other agencies are managing the issue, and what we can learn from them."

READ MORE: Everything you wish you didn't need to know about rats in the Thompson-Okanagan

And if B.C. wants to learn from other provinces it doesn’t have to look very far.

When Norway rats first showed up in Alberta in 1950, the government passed a law that required every municipality to appoint a pest control inspector. It promptly passed legislation that made rat control mandatory and citizens could face fines if they failed to deal with rats on their property. Over the following decades, the province funded aggressive anti-rat measures and the government claims that in the last 20 years no more than eight infestations have been reported in a single year.

"However, the problem is not solved, personnel involved in rat control must continually guard against complacency. Rats have the capability to spread throughout Alberta just as easily today as they could in the past," reads the Government of Alberta’s website.

An Alberta government rat poster cicra 1950.

Image Credit: www.alberta.ca

The difficulty in dealing with rats is clearly highlighted by Haida Gwaii’s experience.

After being introduced by European ships in the 1800s, several islands in the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve declared themselves rat-free in 2016. One year later, the rats were back.

And while Alberta says its rat control is "a source of pride" for its citizens, the province hasn’t outlawed rodenticides.

Ball says that while his company, like the vast majority of pest control companies, does use rodenticides, the chemicals aren’t used as much as people might think.

"We are a little reticent to poison frankly... we never, ever poison rats inside of a house, if we're doing maintenance on a commercial building, we may poison outside,” he said.

Poison isn’t used inside because a sick poisoned rat in someone's residence will likely hide somewhere in the home and then die. This it's likely to leave a mammoth job trying to locate the smelly rotten carcass.

Ball said much of his company’s work involves blocking entrances to homes where rats get in and doing extensive rat-proofing insulation work.

The pest control company owner said rodenticides are generally used outside at commercial buildings some of which have leases mandating pest management.

And Ball says he wouldn’t be opposed to a province-wide ban of rodenticides.

"Kudos for them for banning them if they want to have snap traps only, that's great, I'm all for it, it’s a benefit to the environment, but we're going to need another 10 pest control companies," he said.

He points out it would also be very expensive.

"You can only have so many snap traps in place, those poison bates are our face in the field when we are not around, we can’t be at every location every day, it’s physically impossible to do," he said.

But it has been done. The State of California banned rodenticides on January 1.

Image Credit: ORKIN Canada

Invasive Species Council of B.C executive director Gail Wallin said her organization doesn’t have a stance on banning rodenticides.

"Any invasive species including rats we don’t want to have in B.C, and we want to make sure there's action," Wallin said.

Wallin stresses it's very important for people to report rat sightings, and other invasive species, as the first line of defence.

"It's difficult to eradicate something once it’s well established," she said.

She is however hesitant about an outright ban.

"Based on the work we do, we say, let’s keep the tools in the toolbox," she said.

Wallin said the rats are both invasive species, which eat bird eggs and cause damage to native species.

In buildings, rats can chew through pipes and electrical wires, causing floods and fires. They also carry a lot of diseases.

While coyotes do prey on rats, as areas get developed, coyotes are often pushed out, but the rats remain – and now have one less threat.

And much like the fact no one knows how many rats live in the Okanagan, no-one knows how they got here either.

"There's a lot of speculation, but a lot of them came from Vancouver,” Ball said. "A lot of companies store lumber down on the waterfront and that's where the rats are, (the rats) come up wrapped up in building materials."

Getting an idea of how many rats there are in the Okanagan is no easy feat and Dubois said the research hasn’t been done so she won’t even hazard a vague guess.

For an individual that gets up to half a dozen calls a day about rats, Ball won’t guess either, but he can count the amount of rats traps he uses.

Seven years ago had two traps sat on the shelf and never got used. Last year he went through nearly 3,000.

It’s a clear indication of a problem that is growing.

Dubois said there are multiple factors as to why the numbers are growing and points to prevention as a first line of defence. How garbage and compost are stored are all factors as well as how restaurants dispose of waste.

A curbside compost pick-up program in the Lower Mainland contributed to the issue.

"All of a sudden the bears came out… (and) bears would knock over bins and then the rats would show up," Dubois said.

As long as the rat population keeps growing, and the use of anticoagulant rodenticides remains, it appears society will have to accept that dead raptors and other animals will be caught in the crosshairs.

And the question remains:

"Why are we continuing to do this?" Dubois says. "It hasn't fixed the problem."

To contact a reporter for this story, email Ben Bulmer or call (250) 309-5230 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2021