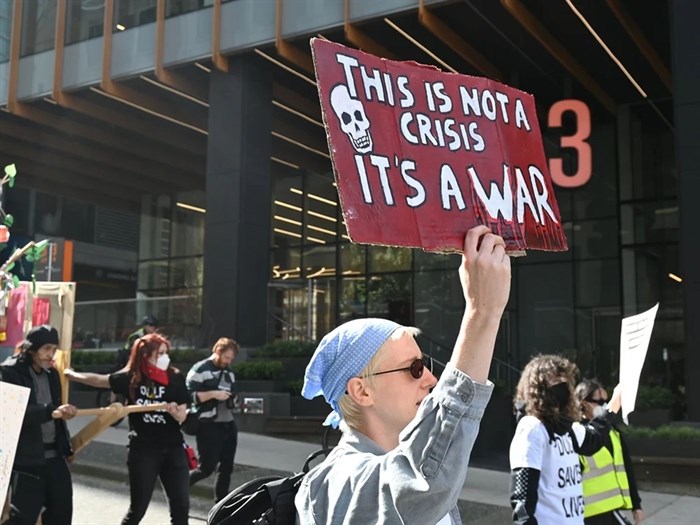

People rallied in downtown Vancouver on Monday to mark the ninth anniversary of the province declaring the toxic drug crisis a public health emergency.

Image Credit: Michelle Gamage, Local Journalism Initiative

April 19, 2025 - 4:00 PM

Toxic drug deaths for First Nations peoples decreased by 6.8 per cent in British Columbia between 2023 and 2024.

This “shows us what we are doing, particularly in the area of harm reduction, is helping,” said Dr. Nel Wieman, chief medical officer of the First Nations Health Authority.

Harm reduction for First Nations communities means “getting to the root wounds that make people turn to substances to cope and really undoing those harms of colonialism,” added Celeta Cook, executive director for FNHA public health response.

While the decrease in fatalities offers some relief, data shows First Nations peoples are still being disproportionately impacted by the toxic drug supply, Wieman said.

She spoke to the media on Monday, marking the ninth anniversary of the province declaring toxic drugs a public health emergency.

In 2024, 427 First Nations people died from a toxic drug poisoning, down from 458 First Nations people who died in 2023.

First Nations people make up about 3.4 per cent of B.C.’s total population but represented 19 per cent of toxic drug deaths in 2024, Wieman said.

First Nations people are dying from toxic drugs 6.7 times more than the general population, which is the largest gap in drug deaths seen since 2016 when the public health emergency was first declared, Wieman said.

Three-fifths of the 427 people who died were male and two-fifths were female, Wieman said, but added this data was based on assigned sex at birth and might not accurately represent Two-Spirit, transgender, nonbinary and gender diverse people.

First Nations women died at 11.6 times the rate of other British Columbian women in 2024, and First Nations men died at 5.2 times the rate of other British Columbian men, she said.

Just over half of the 427 people killed were younger than 40.

Harm reduction is saving lives

Between January 2018 and December 2022, 1,374 First Nations people died from toxic drug poisonings across B.C. Over the same time period 1,024 lives were saved due to harm reduction initiatives, Wieman said. The FNHA calculated these numbers through a collaboration between the FNHA and BC Centre for Disease Control, she said.

Of those lives saved, she continued, around two-fifths can be credited to take-home Naloxone kits, just under 30 per cent to the use of opioid agonist therapy, and one-fifth to overdose prevention or supervised consumption sites.

Cook said the FNHA is expanding its harm reduction resources. It’s launching a resource for youth that recognizes they’re often first responders for friends and family; supporting land-based healing that fosters connection with land, water, community, family and culture; and increasing drug checking services.

The FNHA has also purchased treatment beds; is building treatment centres that offer stabilization and aftercare; and is building healing centres across the province that offer therapy and other traditional wellness modalities, she said.

Wieman said the FNHA is speaking with the province to seek solutions for First Nations people who live a boat ride or a plane ride from pharmacies, after the province said it would restrict its safer supply program, ending take-home safer supply and requiring patients to take their medication in front of a pharmacist.

Over the last year, the FNHA distributed over 5,000 nasal Naloxone kits to 112 communities and taught 379 people, including Elders and youth as young as 12, how to administer Naloxone, why people use substances, and how to have healthy conversations about drugs, Cook said.

During that same period, Cook said, the First Nations Virtual Substance Use and Psychiatry service provided over 1,700 assessments and treatment planning sessions for over 4,000 First Nations people.

There were 3,400 toxic drug poisonings for First Nations peoples attended by paramedics in 2024, most of which were non-fatal, Wieman said. This doesn’t capture data for communities where there aren’t any paramedics, she added.

Decriminalization eases stigma, culture promotes healing

Wieman criticized the pushback against B.C.’s decriminalization pilot project because the program was meant to help reduce stigma around substance use.

The reason First Nations peoples are disproportionately impacted by toxic drugs is complex, she said, but it includes the historic and ongoing impacts of colonialism, such as residential schools, the ’60s Scoop, ongoing child apprehension, systemic racism and a lack of timely access to culturally safe, trauma-informed mental health, substance and wellness support.

Reinforcing stigma only pushes people to use alone, Wieman said. People also might use alone because they’re afraid of losing their children or support systems.

Not everyone who uses substances has a substance use disorder and may be using for a short period of time to cope, she added.

“It is crucial that we work together to eliminate First Nations-specific racism, discrimination and the harmful perpetuation of myths, stigma and stereotypes,” she added.

Stigma can look like telling a person who uses substances that they’re broken, or their spirit is broken, said Kali Rufus-Sedgemore, an Indigenous harm reduction worker and advocate who said they lost their father, brother and “countless” other family members and friends to toxic drugs.

Anti-Indigenous racism in health care can look like having a security guard posted by you and being asked what drugs or alcohol you’ve taken before being asked what’s wrong, they added.

This pushes people away from wanting to access health care or harm reduction.

Culture can be an important part of harm reduction and people should be mindful of what barriers they create to accessing it, such as sobriety, Rufus-Sedgemore said.

Denying people access to culture for any reason equates to “telling them they’re not worthy of the culture or worthy of their own communities,” they said.

Cultural practices can be a powerful healing tool.

Earl Crow, a cultural support worker in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside who also spoke Monday, said he regularly takes people to stay in a teepee near Lillooet so they can do land-based teachings about medicine, go fishing and swim in the lake.

“It’s amazing,” he said. “When I drive them back I don’t even know who is in the back seat anymore because they change,” he said.

Helping Indigenous people get to Sundance and powwows to connect with culture also “changes who they are,” Crow said.

— This article was originally published by The Tyee

News from © iNFOnews, 2025