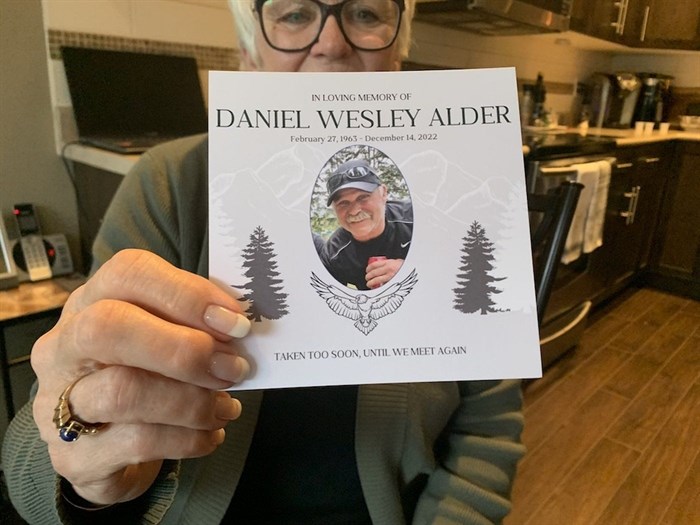

Carolyn Alder, Dan’s mother, says her family has been told nothing about his workplace death at Deltaport a year ago.

Image Credit: Zak Vescera, Local Journalism Initiative

December 16, 2023 - 6:00 PM

Before he became a statistic, Dan Alder was a hockey player, a mechanic, a brother, a busybody and a man who had raced motorcycles down mud roads and worked in logging in Haida Gwaii.

But to his daughter, Shauna, he was also a cheerleader.

Whenever her brother had a hockey game, Alder was there in the stands — if he wasn’t coaching himself. When she took up gymnastics, few parents ventured to the long practices. Shauna calls it “the most boring thing you could probably watch.”

But her dad would be there.

“He was my brother and I’s biggest fan,” said Shauna. “He was always there to support us.”

A year ago, on Dec. 14, Dan Alder went up 23 flights of stairs on a crane at Deltaport, the container ship terminal where he worked as a mechanic, and never came down. The elevator wasn’t working, a frequent occurrence, workers say.

Alder died shortly after an unspecified medical emergency while on top of Crane 8, 56 metres in the air.

For months, that was what Alder’s family knew about the circumstances of his death.

The day after Alder died, a federal inspector visited Deltaport. He later reported six safety violations related to his death, including a finding that the company had failed to develop an emergency response plan for its cranes, and that it failed to assess the risks of working on those cranes when their elevators were out of service.

The federal government has since launched a continuing investigation into the matter.

But no one told the Alders about that investigation, or the inspector’s original findings after he died.

Carolyn Alder, Dan’s mother, said the company never told her about the investigation into her son’s death. Neither did the federal government or the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 502, which represented Alder.

Carolyn and Shauna are speaking publicly about Alder’s death for the first time, in the hopes he is remembered for what he did in life and not just how he died.

Carolyn said she also wants an acknowledgment, and an explanation.

“I feel that they should have kept the family involved,” Carolyn said.

‘The kids had the run of the place’

Dan Alder was born the second of three boys. When he was a young child, the family moved from Vancouver Island to Mackenzie in the north of B.C., which at the time was an “instant town” set up for the logging business.

“It was totally new. There was nothing there,” Carolyn said. The roads were mud. The nearest grocery store was nearly 200 kilometres away. The boys grew up with horses, a snowmobile and “the freedom to be kids,” Carolyn said. “They had the run of the place.”

In Mackenzie and in Port Alice on Vancouver Island, where the family later moved, Carolyn said, Alder seemed to do just about everything. He played basketball and baseball, raced motorcycles up and down dirt roads and excelled at curling. “If you didn’t keep him active, watch out,” she said with a laugh. “Because otherwise he got into trouble.”

But his love was hockey. Alder skated for the first time when he was two. When he was nine, he was declared the best player of his age in a Skills BC competition. He was flown down to Vancouver to accept his award on the ice before the Vancouver Canucks played.

Alder didn’t like school, and he didn’t like downtime. Carolyn said he always had to be moving, competing or fixing or improving something.

“He’d sooner be competing. So he was very driven when it came to sports and doing things,” Carolyn said.

Alder dropped out of high school in Grade 12 and began working in the forestry industry, including a stint working in logging in Haida Gwaii. Around the same time, he began his apprenticeship to become a mechanic.

He met his wife, Brenda, while they were living in Pemberton; the two would have been married for 30 years this past September. They had two children and settled in Langley.

Shauna says her father was a dedicated family man. He loved the outdoors and he and the kids would take trips to go camping.

Alder encouraged both his kids to play sports and ardently supported them through it. He would coach and referee hockey and was an avid supporter of local teams.

Throughout it all, Carolyn said, Alder was the kind of guy who would drop everything to lend a hand.

“He gave so much to so many, and always with a smile,” Carolyn said.

“He was the best person,” Shauna said. “This shouldn’t happen to anyone, but let alone to a man who gave everything for everybody.”

‘We don’t want someone to go through what we went through’

In the meantime, Alder had begun work at Deltaport, a massive container terminal west of Tsawwassen.

Alder’s co-workers described him as a loyal friend and a talented mechanic who was a mentor to many in the 200-person department.

“I knew that he was such a hard worker. He really knew what he was doing,” Shauna said. “He had so much experience and he was the go-to guy. He had the little tips and tricks and he knew things inside and out. He knew the people he worked with. He had those jokes. He had those connections.”

He was also a stickler for safety.

More than once, Carolyn said, Alder told her that he had complained about broken elevators on the 56-metre-tall gantry cranes that lift cargo off the backs of ships.

Carolyn said he had spoken to managers multiple times about the elevator on Crane 8, where Alder had been working on the day he died.

The Tyee has spoken to multiple Deltaport employees, including a former union official who said those elevators were frequently broken, raising fears that first responders could not easily reach someone if they were to suffer an injury or a medical emergency while atop the crane.

Lorne Stevens, a former vice-president with the union who quit after Alder’s death, said it was a years-long issue that members regularly submitted complaints about.

Stevens told The Tyee in a previous interview that Alder had been changing a trolley wheel at the top of the crane when he suddenly collapsed. Because the elevator was broken, first responders had to climb the stairs to the crane to reach him.

They then transported him to the ground by placing him on a platform used for maintenance work and lowering him 13 metres so he could be within range of a cherry picker on the back of a fire truck.

Alder died at the scene. No official cause of death was given and an autopsy was not done.

“We knew very little,” Shauna said. “We were told that it was a possible heart attack and they couldn’t reach him in time, and that was pretty much it. We had very little information afterward.”

Shauna and Carolyn say they were not told of the investigation into Alder’s death, either by the company or by ILWU Local 502.

Marko Dekovic, a spokesman for Global Container Terminals, which runs Deltaport, said the company does not “discuss internal processes outside of our organization.”

ILWU Local 502 did not respond to multiple requests for comment, including specific questions on why the Alder family was not told about the circumstances of his death.

That union issued a brief statement when Alder died, mourning him as a “well-known and respected member of our local.” When the Alder family hosted a memorial gathering at one of his favourite pubs, Carolyn said, so many ILWU maintenance workers showed up that they couldn’t fit inside. On April 28, the International Day of Mourning for workers killed on the job, some ILWU members showed up to a Vancouver ceremony wearing placards with Alder’s name.

But the union has never commented publicly about Alder’s death. Multiple sources contacted by The Tyee have said the union had instructed them not to speak on the matter.

Carolyn and Shauna eventually learned about the investigation into Alder’s death by reading reporting in The Tyee, which had tried to contact the family multiple times before publishing initial stories.

Carolyn says she wants an apology and acknowledgment. Shauna says that most of all, she wants assurances the issues at Deltaport have been fixed.

“We don’t want someone else to have to go through what we went through. It’s hard reading what you wrote... that it could have been prevented, that it was unnecessary,” Shauna said.

Shauna said she had little doubt her dad would want the same thing.

“There’s not a doubt in my mind that he would be fighting if this happened to anyone else.”

— This story was originally published by The Tyee.

News from © iNFOnews, 2023