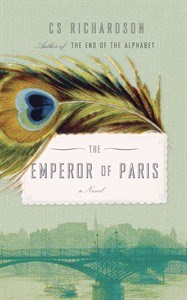

The cover of "The Emperor of Paris" by C.S. Richardson is shown in this handout image. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO - Random House of Canada

August 14, 2012 - 4:57 PM

TORONTO - Author C.S. Richardson was intrigued by the idea of setting his new novel, "The Emperor of Paris," in a time before mass media and creating an illiterate protagonist who finds ways other than TV and film to drive his imagination.

"In present-day society we have all kinds of things that inform our imagination — television, movies, reading, all those kinds of things," Richardson said in a recent interview to promote the book, which hits stores this week.

"So I thought to myself, 'What if you couldn't access those things? Where would your imagination come from? What would drive your imagination?' Let's remove those things. Let's have a protagonist that can't access the normal things that we would all access that would drive our imagination."

The book's protagonist, Parisien baker Octavio, suffers from "word blindness." His father, Emile Notre-Dame, can concoct the perfect baguette but can't read either, and teaches his son to invent stories inspired by pictures in books and newspapers.

Richardson said he also wanted to create a cast of characters who are flawed, whether the deficiency is brought about by themselves or is imposed, and to explore how they would deal with the setbacks and ultimately interact.

Just a few streets away from the bakery is Isabeau, an art restorer who face is scarred and who loses herself in books. Isabeau and Octavio might never have met except for a curious chain of coincidences involving an impoverished painter, a jaded bookseller and a book of fairy tales.

Richardson (C.S. stands for Charles Scott, but he goes by Scott) is also vice-president and creative director at Random House of Canada and has won multiple awards as a designer during the approximately 30 years he's worked in publishing.

But novel writing is something he only began about 15 years ago. "I was looking for a different way to scratch that book itch. I've always loved books and I always will, but I was looking for a different way to express that."

"The End of the Alphabet," published in 2007, won the Commonwealth Prize for best first book. Richardson said it took him about five years to complete each book.

Initially he had to write in the evenings after his daughter Hannah, now 18, had settled down for the night and that has become his routine. "The Emperor of Paris" (Doubleday) is dedicated to her and his son Alexander, 27.

He also thanks his wife Rebecca, who reads everything he writes before he shows it to anyone else. "She's brutally honest. She's reads voraciously, so I trust her opinion implicitly."

She suggested the fire that burns Octavio's precious library, painstakingly assembled based on a volume's colour and size to fill every nook and cranny of his apartment above the bakery.

"It was the one thing I needed to kick it all off," said Richardson, 57.

Then he created a fable about the emperor of Paris that is a microcosm of the book.

"The basic premise of the book is to overcome his embarrassment, his flaw, here's how (Octavio) solved the problem. His father tells him the story that his father had told him about this fictitious emperor who suffers the same sort of embarrassment, thinking he's unwise and that people will laugh at him. ... His father implants that story in him and he takes it to the next level."

The bookseller Henri has a tactile and visual appreciation of books instilled in him by his grandfather.

"One of the things that I love about books is not just the reading of them but how they feel," Richardson explained.

"To my way of thinking a physical book is the perfect invention. ... It's the right size, it feels right in your hands, you don't have to plug it in, you don't have to charge it up and, as a designer, as a person who constructs books, I'm doing the same thing more or less that people were doing 500 years ago."

He said writing about Henri also gave him the perfect platform on which to emphasize that the way a book feels is part of the experience of reading.

"I will be the first to admit as I was writing those parts there was a little bit of a soapbox involved because I'm a real book person. I know why there are e-books, I know why that's happened, I know what they do. They're not for me. So it was my sort of standing on a soapbox to defend the real book, the physical book."

Richardson's writing is spare and concise and he's proud of that. "It's a real discipline. It's really tough to pull that off. I'm getting better at it slowly but surely, but also that's the kind of writing I like to read."

When he began writing he spent a lot of time rereading classics such as those written by Kipling and Hemingway, but he looked at them in a new way to see how the authors dealt with dialogue, sentence and paragraph structure.

Richardson uses a few well-chosen words to create a character, much like the artist Jacob in the book who can depict a person or scene on his canvas with a few simple pencil strokes.

"The other side of it is that I trust the reader implicitly. I think readers are the smartest people on the planet and so ... I don't need to whack them over the head with too many adjectives and all those kinds of things because I think the reader is part of the process and they will bring their own thing to it one way or another.

"I trust them to know what I'm talking about."

Richardson is working on his third novel.

News from © The Canadian Press, 2012