Image Credit: Compilation/Jennifer Stahn

September 23, 2015 - 8:00 AM

“Your father died ten minutes ago.”

The nurse’s terse conveyance over my smartphone left me dumb.

The anticipated but dreaded call arrived mid-afternoon last Wednesday. I’d been on the road plying my workaday trade; and the whole way back from Fernie that day, I had been periodically interrupted by thoughts of my dying dad. How was he keeping? Was he in pain? Would his wish finally to be rid of a failing body soon be realized?

He got his wish at last.

We’d said our good-byes many times over by the time that “his time” came to its end. When I arrived at the care home where he lay upon his final bed, he was gone. The body that lay there wasn’t his anymore. Somehow the absence of spirit diminished his fading frame even more dramatically than when I had seen him last, only a few days before.

Mum was sitting next to the bed, her year-long vigil over. We hugged one another, felt the heaving in one another’s breasts, and sat quietly for a time. “Na ja, Jeffrey,” she said. “He finally got his wish.”

And with that the remembrance began...

My mother and father were refugees to this country. Both had arrived on the prairies starting out from fatherless homes in Soviet Ukraine and ended up meeting in Bible-belt southern Alberta. It was in Coaldale that they would learn English and begin their exciting new lives in a country far more peaceful than Stalinist Russia or war-torn Germany.

You could call my father a religious humanist. Steeped in the greats of German literature and philosophy, my father would go on to become an academic at a time when the humanities flourished in North American universities. It was a time when students (like me, his youngest son) could actually go to university for the sole purpose of enlarging their worlds through the sheer joy and challenge of absorbing the classics of the Western canon.

And part of that great humanist tradition was the necessity to know The Bible, arguably the cornerstone of our intellectual heritage.

As nominal Christians, my parents ensured that their three boys would be steeped in The Bible. And among the first books that I remember receiving from my Dad were an Illustrated Children’s Bible and a copy of John Bunyan’s Christian allegory, Pilgrim’s Progress.

Inspired by my earliest Bible readings I quickly identified with young Joseph and feared that I would one day be sold into slavery by my scheming older brothers. I identified too with young Isaac, who would be offered by his own father Abraham to a demanding God as a sacrifice before an angel stayed his hand and provided a surrogate in the form of a ram.

And with Bunyan’s allegory, my childhood lexicon would explode with new additions inspired by character names like Obstinate, Timorous, Hypocrisy, Discretion, Piety, Prudence, Wanton; and, perhaps my favourite for the sheer joy of pronouncing aloud and examining its delicious quadrasyllabism on the printed page, Beelzebub.

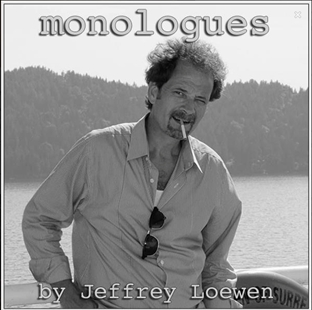

Harry Loewen

(JEFFREY LOEWEN / iNFOnews.ca)

Of course, beneath the surface of these texts, so revered by my father, there was some serious stuff going on. But as I matured into the hubris of literate pre-pubescence I would come to reject The Bible as a source of intellectual and spiritual succor.

As is so often the case, we reject first what we think we know all too well. It’s a mistake that many never recover from.

I recovered from my rejection of The Bible well after I had spent a good deal of time studying literature and philosophy at university. Part of the recovery came as a result of realizing the deep impact that The Book of Books had on my father’s own intellectual journey as well as my own.

Understanding the greats of English literature (Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton and Blake all the way to Greene, Murdoch, Atwood and Amis), or continental philosophy (Aquinas, Descartes, Spinoza, Kant, Hegel and Marx all the way through to Charles Taylor and Slavoj Zizek), or even my favourite song writers (Dylan, Cohen, Mitchell, Jagger/Richards, Lennon and McCartney all the way through to Tom Waits and Nick Cave) -- all of these greats would remain opaque to me without the intercession of Biblical narratives.

Readers may wonder at the why of dwelling on The Bible in the midst of rueing the release of my father to another stage at the end of this life that he’s led under the sun.

His fervent wish for an end to his sickness and suffering these last two years was mitigated, at least in part, by discussions that we were able to undertake while he was still well enough to continue considering the mysteries of this all-too-fleeting life. Our discussions of the heart-rending Book of Job, so evocative in its descriptions of a good man beset, like a plaything of the gods, by personal plagues too numerous to enumerate here, will resonate with me to the end of my own days under the sun.

And as my dad entered his final months when the pain made him bid his books a final farewell, we would remind each other of the wisdom in what would be perhaps our favourite, and surely the most poetic of Biblical texts, the Book of Ecclesiastes.

For it is written there by an aging King Solomon, a man who possessed more than anyone in the history of the world to that point (we are told), “Vanity of vanities... All is vanity.” It is impossible for me to reject the wisdom of these words and how they are the very nature of life “under the sun.”

Ecclesiastes beckons with the sage finality that all things, all folks, must pass. In the same remarkable book, we acknowledge that everything under the sun has its season and that life itself is a gift that is short and seemingly without purpose.

And yet it is a beautiful thing to share this life with one, like my dear dad, so willing to impart these insights into this life lived under the sun.

Rest in peace, Dad. All is well. Under the sun.

— Jeffrey Loewen is a Kelowna-based writer who plays music by day and politics by night

News from © iNFOnews, 2015