Jacob Philp is healthy, happy and clean after completing treatment in Vernon.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON - REPORTER / iNFOnews.ca)

September 02, 2018 - 12:00 PM

“WE HAVE KIDS DYING. KIDS WE KNOW, THAT WE'VE HELD HERE, AND THEY'RE DYING BECAUSE WE DON'T HAVE THE RESOURCES TO GET THEM HELP.'

It’s 2 a.m. on a skin-numbing winter morning when Jacob Philp and a buddy sit down at an empty bus stop to use.

Neither of them are dressed for the weather. Philp is wearing pyjama pants and a thin shirt. He’s on bail for break-and-enter charges and knows he’s breaching his curfew.

After using, he shuts his eyes and nods off. When he wakes up, the sun is rising. His friend’s head is resting on his shoulder and Philp can see icicles formed on his eyes and nose.

It’s cold enough that Philp should be able to see his friend’s breath in the air, but there’s nothing. He runs a few blocks to his dad’s house and phones 911. It’s too late.

This happens while Philp is on a waiting list for Bill’s Place, a treatment program in the North Okanagan run by a non-profit society. The loss and and anguish of losing yet another friend to overdose only makes him want to use his drug of choice — fentanyl — even more to make it all go away.

It could have been him that night.

Somehow, over roughly two months of waiting and more than a dozen nearly fatal overdoses, Philp makes it to Bill’s Place. The treatment works. He gets clean, learns how to enjoy a real belly laugh again, rebuilds relationships with his family, gets a job.

Many don’t get that chance. They end up overdosing and dying on the streets, in bus shelters, and homes before they get there.

So far, the headlines about the B.C. government response to the opioid crisis have largely centred on the province-wide harm reduction campaign, but clean needles and safe consumption sites simply keep people alive.

The four pillars of community response to substance abuse are harm reduction, prevention, enforcement and treatment.

This story is about treatment. And unlike harm reduction, publicly-funded residential treatment in the Interior has actually declined since the opioid crisis began.

THE OPTIONS

Three options await anyone seeking residential treatment services in the Interior. For a minimum $17,000, you can go to a private facility and skip the waiting lists. Otherwise, your options are a publicly-funded facility, or one run by a non-profit organization but either way, your real cost is joining a waiting list.

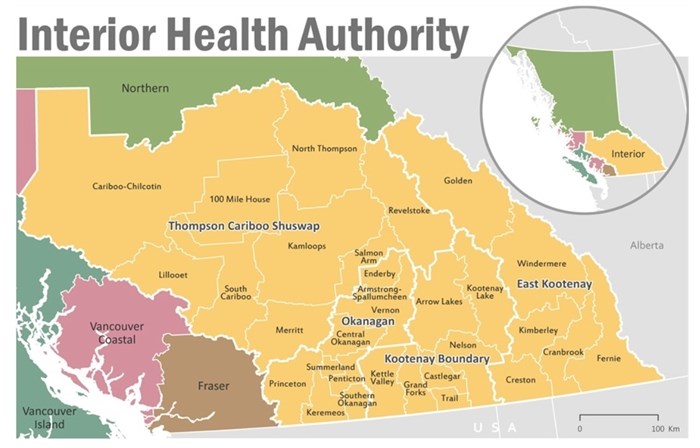

Interior Health funds 56 adult treatment beds within its expansive coverage area, home to 749,853 people and where 241 people died last year due to an overdose.

But the numbers are also tricky since 36 of those beds are jointly funded by the First Nations Health Authority and are oriented for First Nations, leaving just 20 other beds to serve the entire region.

Image Credit: Interior Health Authority

A few more options are available around the province, mainly the Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island, but their waiting lists are also province-wide and often specialize for women or mental illness patients for examples.

Even fewer options exist for youth. The Interior has just four publicly-funded beds for 17- to 24-year-olds in Ashnola at the Crossing in Keremeos and intake is through a provincial referral process. If beds are available, youth may also be sent to Vancouver's Peak House, or the Nechako Youth Treatment Centre in Prince George.

Private facilities, and programs run by non-profit agencies such as Bill’s Place, help fill the gap in treatment options for adults, but waiting lists abound for anyone without thousands of dollars to spend on treatment.

NUMBER OF BEDS HAS DROPPED

Interior Health’s 56 treatment beds are split between the 36 beds at Round Lake Treatment Centre in Armstrong and Bridgeway in Kelowna, which has 20. Round Lake has been receiving funding from Interior Health since 2009, and Bridgeway since 2013.

Round Lake also gets funding from the First Nations Health Authority and has an intake every five to six weeks. The program incorporates First Nations healing and ceremonial practices and while you don't need to be Indigenous to attend, the vast majority of clients are.

Bridgeway takes clients every six weeks, alternating for men and women which can complicate waiting lists even further. They opened in 2013 to fill a gap left by Kelowna’s Crossroads Treatment Centre, which had a 36-bed contract with Interior Health when it shut down. Despite the new contract with Bridgeway, the Interior was left with 16 fewer beds, coinciding roughly with the start of the overdose crisis.

Interior Health couldn’t tell us how long waiting lists are for its 56 funded beds — they don’t track that data — but Round Lake says their waitlists can be as long as six months.

Executive director of the Round Lake Treatment Centre Marlene Isaac.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON - REPORTER / iNFOnews.ca)

Executive director Marlene Isaac was brutally honest about the impact of waiting lists.

“We do lose clients, they’ve died going back out into the community because they can’t keep clean until the next treatment program begins,” Isaac says. “In today’s environment and in light of the opioid crisis, individuals who are not able to access safe living facilities while awaiting treatment (or) treatment programs are at great risk of relapse and possibly death.”

Like most treatment centres, Round Lake requires two weeks of clean time prior to admission. That's another challenge given the shortage of detox beds; there are 40 publicly-funded detox beds for adults and four for youth in all of the Interior Health Authority. Round Lake is trying to bridge that gap by opening a pre-treatment and detox centre.

“I USED THE DAY I GOT OUT OF DETOX”

Philp knew he was supposed to detox before going to Bill’s Place. He got himself booked in at the Phoenix Centre in Kamloops — took his last hit of drugs on the way there — and spent two weeks on a methadone taper. He walked out clean, but it didn’t last long.

“On my way home from detox I was texting my drug dealer saying 'hey, can you wet my whistle?'” Philp says.

He overdosed that night.

When he left detox, Philp still didn’t have a start date for Bill’s Place, which doesn’t have set intake dates but rather accepts people as space becomes available. The idea is that longer-term clients can be mentors for newer ones.

Philp began calling Bill’s Place every day. Sometimes he spoke to a staff member, but mostly he just left messages.

On a February morning while staying at his dad’s place, he accidentally set off the fire alarm while smoking drugs. Everyone was evacuated from the apartment building and Philp got evicted.

“I use the last of my drugs, I sit down in the snow and I just start crying. I was praying for an end. I needed something to change,” Philp says.

At that moment, he crossed paths with a former girlfriend — someone he had regrettably ripped off in the midst of his addiction. She showed him some kindness and let him come to her house to call his mom. He didn’t have a cell phone.

“It was, like, 5 a.m. and I called my mom, and she’s like, 'oh my god, I’ve been trying to get a hold of you. Bill’s Place has a bed for you',” Philp says.

Evicted, essentially homeless with no address and violating his curfew and probation, the bed was Philp’s ticket out of jail and, hopefully, to a better life. If he hadn’t called his mom — or had a supportive parent to call — he likely would have lost his space to the next person on the waiting list.

THE WAITING GAME

Bill’s Place is not unlike other treatment programs in the Interior such as Freedom's Door in Kelowna that are run by non-profit community organizations trying to make up for gaps in service. It opened in 2013 in direct response to a lack of residential treatment options in the North Okanagan, Turning Points Collaborative Society co-executive director Kelly Fehr says. At that time, staff were struggling to expedite the movement of people from their shelter into a treatment program.

“Sometimes we’d get people into detox, but there’d be no treatment option when they finished,” Fehr says.

The society went into debt to open Bill’s Place and the program quickly filled and accumulated a waiting list. It operated with public donations and the society’s willpower until 2017 when Interior Health came on board with funding for eight beds. The funding falls under what Interior Health calls “supported recovery,” not treatment, but it’s an important part of what Bill’s Place does. The program has three phases: three months of primary care followed by seven months of extended, sober-living with programming, and finally, an option for affordable housing.

The waiting list for Bill’s Place is about two months.

“We turn people away on a regular basis because we don’t have room to take people in. We need more sober living and we need more treatment beds,” Fehr says.

In a perfect world, a user who wants to start treatment should be able to do so within a week, Fehr says.

“When they have that moment of clarity and they decide enough is enough, if you can’t get into treatment right away, that motivation, that ability to carry through, diminishes very quickly,” he says.

Bill’s Place, like most non-private treatment centres, can help clients access the program at an affordable rate either through income assistance, disability or other grant programs. Those who can pay are asked for $2,000 a month.

AVOID WAITING LISTS, IF YOU CAN AFFORD IT

The 13-bed iRecover treatment centre in the North Okanagan.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED/iRecover Okanagan

Privately run facilities like iRecover Okanagan, located in Lavington, allow people to skip waiting lists and go straight into detox and treatment. Director Jodi Smith says lengthy waiting lists were one of the reasons why iRecover decided to open a facility in the North Okanagan (its other locations are in Alberta, Newfoundland and Palm Springs, Fla.).

The 13-bed facility doesn’t have waiting lists and staff can actually get people in the same day that they call, Smith says.

The price is $17,000 for a four-week program, or $28,000 for the extended eight-week program, plus tax. Clients get private rooms, medical and counselling staff, outings and meals prepared by on-site chefs. Some clients are able to get the treatment covered through company benefits and other times unions will pay the fee, Smith says.

So far, since opening in February of 2017, 48 people have graduated from the program.

“We see all walks of life,” Smith says. “Addiction does not discriminate. We see nurses, teachers, CEOs, single moms.”

One of the biggest gaps in the area, she says, is addictions services for youth. iRecover is only open to people 19 and over.

“We do get numerous calls with regards to youth with addictions issues,” Smith says.

“THEY’RE DYING”

Celine Thompson’s voice cracks when she talks about the lack of youth treatment services not just in the Interior, but in B.C. She’s the executive director of Bridgeway in Kelowna, which has a contract with Interior Health to provide 20 treatment beds for individuals 19 and older. That service can’t meet the demand for adults — wait lists of three to four months are common — but it’s the severe shortage of youth beds that she says is the biggest travesty.

“In our detox program, we have people admitted as young as 12 years old,” Thompson says.

Once out of detox, it's hard finding somewhere to send them for treatment, she says. There are fewer than 50 publicly-funded treatment beds for youth in the province. The four available in Keremeos — the only facility in the Interior — is also for youth 17 and older, leaving nowhere for younger kids, Thompson says.

Even if a child or youth is lucky enough to get a bed somewhere in the province, sending them out of their community, away from their support networks isn’t ideal, she says.

“That little window you have with them where they have the courage to pursue recovery, it can close on the car ride there,” she says.

Thompson has to pause during the interview to collect herself. The problem is just that heartbreaking.

Her co-worker, Kelly Paley, fills in the silence.

“When you hear Celine’s voice break up it’s because we have kids dying. Kids we know, that we’ve held here, and they’re dying because we don’t have the resources to get them help,” Paley says. “These are our kids. They’re not numbers or statistics. We can change these paths.”

Bridgeway recently announced plans for a 16-bed youth treatment centre, something Thompson hopes will break ground in two years. The project would likely need a combination of funding from Interior Health and B.C. Housing, but Thompson says the outlook is promising.

“I think the government is really just catching up to decades of no investment,” she says.

NOT JUST TREATMENT BEDS

So far, we have explored mainly residential treatment — the most intensive form of therapy which includes lengthy stays, medical care and counselling. According to many support workers, this is where the magic happens.

But Interior Health says it’s not the only answer.

Rae Samson, the administrator for substance use services with Interior Health, points to numerous day programs throughout the region as well as drug counselling, therapy, supervised consumption sites and other outpatient services.

Samson says residential treatment is just one piece of the puzzle and shouldn't be looked at as the only answer.

“We have a full continuum of options because everyone has a slightly different journey,” Samson says.

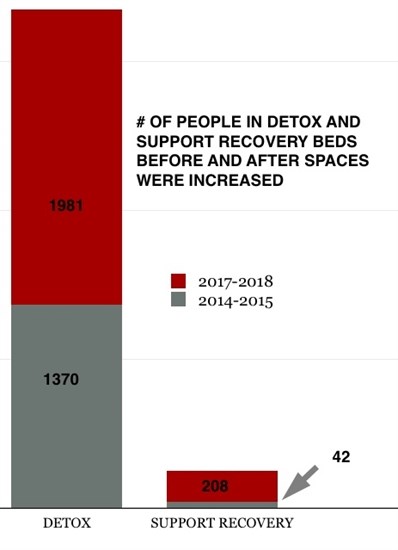

Interior Health added 73 substance use beds since new funding was announced in 2016. None of those were residential treatment beds.

Of them, 57 were support recovery beds — safe, substance-free housing for clients awaiting treatment, returning from treatment or transitioning to a more stable lifestyle — and the remaining 16 were detox beds. Those resources were badly needed and statistics show utilization spiked as soon as more beds were added.

Even when residential treatment is needed, Samson disagrees that it’s imperative to get people in immediately.

She says it’s quite rare for someone to go straight to residential treatment early on in their journey to recovery.

The first line of treatment for an active opioid user, for example, is usually to get them on an Opioid Agonist Program, replacing their street drugs with methadone or suboxone, Samson says. Once stabilized, they would work with a drug counsellor on what happens next.

“Residential treatment is a planned experience. Waiting, as long as you’re working with your counsellor, can be very effective. They would do prep work and get ready for that experience,” she says.

Some people might not ever need intensive residential treatment, she says.

“I think often in popular culture we talk about residential treatment as the only treatment, but it’s part of a much larger continuum,” Samson says.

(CHARLOTTE HELSTON - REPORTER / iNFOnews.ca)

Interior Health has placed a big emphasis in recent years on reaching people with, or at risk of developing, substance use problems, including creating new hospital connection worker positions to provide outreach to people admitted to emergency suffering an overdose.

But despite the increased services and usage, the number of residential treatment beds remains lower than it was in 2013.

Until utilization rates for all its substance use services are reviewed, Samson couldn't comment on what more is needed, or where in the continuum of care.

THE OUTLOOK

It’s better today than when Philp went through the system a few years ago. Back then, he says no one ever gave him information about treatment options during his overdose visits to emergency. He found out about Bill’s Place from a family friend.

“I had no idea what was available. I thought treatment was expensive,” he says, making reference to resort-style treatment with pools and private rooms. “If someone had handed me a pamphlet with available treatment options in the Okanagan and just some information on how affordable these programs are or that the government is willing to help, that would have prompted me to be much more interested,” he says.

Now, Philp would be met with a hospital connection worker established to do just that — let people know what’s available and help them on to the next step. But the one area that changed Philp’s life more than anything else — intensive residential treatment — remains fraught with waiting lists.

Philp was surprised at how well, and how quickly, residential treatment worked for him.

“What treatment can do for a person is unreal. It’s mind blowing how much it can change a person’s life. Sure, not everyone who is an addict wants to change, but a lot of us do want that change,” he says. “When you have so many people struggling from addiction and overdose — I think everyone knows someone affected by it — more needs to be available.”

Philp spends his days now as a residential worker for Turning Points Collaborative, helping others overcome their challenges. He’s been where they are, and he knows firsthand that it’s possible to change. Instead of committing petty thefts and spending time in front of a judge, he’s earning an honest living and making a difference for others.

“There are people who really do want to change and they come to me every day and I tell them exactly what I did and they start calling every day, just like I did,” he says.

It takes effort to get there, and hard work once you’re inside, but the results are life-changing, Philp says.

“One of my highlights was the first time I had a real belly laugh where your cheeks are so sore from laughing. I hadn’t had that in years. You don’t have that in a heavy addiction. It was just some silly thing and a group of us were just howling. I thought ‘oh my god, that felt good.’ Things start coming back to you in treatment and make you realize how amazing life is when you can feel things again. I remember my first good cry too…. It’s a gift to be able to feel that.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Charlotte Helston or call 250-309-5230 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2018