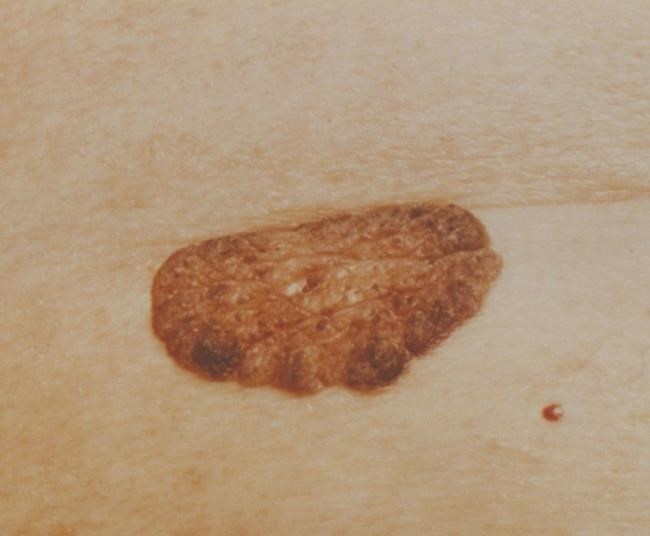

A seborrheic keratosis on a hand is shown in this undated handout photo. Middle age often carries with it a number of advantages, one of which is a clearer complexion. But as acne becomes a distant memory for most people, other issues arise to plague aging skin.

Image Credit: THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO - American Academy of Dermatology

August 18, 2015 - 7:00 AM

TORONTO - Middle age often carries with it a number of advantages, one of which is a clearer complexion. But as acne becomes a distant memory for most people, other issues arise to plague aging skin.

Sun spots, age spots, liver spots, granny warts — whatever you call them, brown pigmented spots are common eruptions as we age.

Dermatologists don't use these terms, knowing that what one person calls a liver spot another will call an age spot. But assessing and excising these pigmented spots is a daily event for skin doctors.

"Pigmented lesions and brown spots are a huge part of dermatology," says Dr. Lisa Kellett, a Toronto dermatologist who works at the clinic DLK on Avenue.

"Sometimes they just want reassurance," Kellett says of the patients she sees with these skin spots. "And other times they say, 'You know, I really hate the look of this; can you get rid of it for me?'"

There are two main types of these pigmented brown spots, solar lentigines and seborrheic keratoses. The good news is that both are benign; they are not early manifestations of skin cancer.

But people should not self-diagnose what they are seeing, Kellett says. She tells her patients she wants to see them if they develop new spots or moles, or if existing ones change.

Dr. Benjamin Barankin agrees.

Medical director of the Toronto Dermatology Centre, Barankin says these types of pigmented brown spots are not directly linked to a higher risk of skin cancer. But these spots pop out when people are older — which is also the time when the risk of developing cancerous melanomas increases.

As well, people who have these spots may become complacent — taking reassurance from the fact they were once told those ugly brown patches aren't skin cancer — and miss a melanoma hiding among an array of pigmented spots on their backs, Barankin says.

So what are solar lentigines and seborrheic keratoses?

Let's start with lentigines. You may never have heard the term, but if you can picture the hands of an elderly white adult, you probably know what they are.

As freckles can dust the nose and the cheeks of some fair-skinned folks, brown spots can mottle the skin on the back of some aging hands.

Lentigines or lentigos are like freckles, says Barankin. But where a true freckle will fade in the winter when sun exposure is limited, these spots do not go away on their own.

Lentigos are the result of sun exposure. If you are fair skinned and you don't want them dotting the backs of your hands, limiting sun exposure or protecting your skin with a sunscreen with a sun protection factor, or SPF, of at least 30 is advised.

Slather it on, says Barankin, who notes most people apply about one-third to one-half of the recommended amount of sunscreen.

Some commercial bleaching creams will help fade these spots, but may not get rid of them entirely if they are dark and have been on the skin for a while.

Dermatologists can zap these spots off using either a laser or liquid nitrogen. The procedure is not covered by medicare. And if your skin is prone to developing lentigines, unless you protect it from the sun you will likely develop more.

The other type of pigmented brown spot is a seborrheic keratosis — or keratoses, if you have more than one. People who develop these crusty, dark brown spots often do.

Barankin sees patients with dozens of these spots, which are generally found on the torso. They are not caused by sun exposure.

"You cannot prevent them," he says. "It's your genetics and getting older."

Dermatologists can also zap off seborrheic keratoses, using the same techniques as they do for lentigines.

"For the flat ones, it has a success rate of between 85 and 90 per cent with one treatment," Kellett says of laser therapy. "It depends on how thick it is. The thicker they are, the more difficult they are. But it's a very good treatment."

Really thick keratoses that have been around for a while may need to be cut out, she notes. And both she and Barankin say if you don't like these spots, it's easier to get rid of them when they are new.

"Whether it's the keratosis or the lentigo, they will come off easier the earlier you get at them," Barankin says.

News from © The Canadian Press, 2015