Kelowna Museums curatorial manager Amanda Snyder inside the new winter house display.

(MARSHALL JONES / iNFOnews.ca)

October 09, 2021 - 12:00 PM

This story was first published in 2016.

KELOWNA - It’s never been hidden anywhere; you can find it in gift shops, on T-shirts and even cemented into popular tourist spots in the B.C. Interior. It’s the subject of trademarks and copyright, a character in books, TV shows, movies, stories and even a logo on a hockey jersey.

Ogopogo, the ‘sea monster’ in Okanagan Lake, has taken many forms since the word first appeared in the 1920s when it was culturally appropriated, stripped shallow for marketing and sold to tourists.

N’ha-a-itk, however, has existed for thousands of years, rich with depth and meaning. It informs the dreams of artists and remains part of the Okanagan, a word for this land that inherently includes its people who’ve been here for thousands of years.

N’ha-a-itk is a wonderful story, unrecognizable from Ogopogo, but it’s not one you’ll read here.

It’s not our story to tell.

Recognizing that, however, is what this story is about.

***

On the City of Kelowna's 100th birthday in 2005, the city commissioned artists to create a video series to commemorate the historic occasion.

When artist Jayce Salloum dominated the series with terra incognita, a 30-minute presentation focused entirely on Westbank First Nation people describing the devastating impacts of contact and colonialism, the city refused to accept it, wouldn’t show it and made noises about wanting its money back.

Instead of recognizing this crucial part of the city’s history and extending a hand to a neighbour, it earned international recognition for repeating its mistakes.

The Kelowna Museum found itself in a similar position recently and took a dramatically different approach. In 2014, the Museum underwent a painful critique by UBC Okanagan students assessing how it exhibits indigenous history.

It showed plenty of examples of oversights like native artifacts that weren’t Interior Salish or leaving visitors with the impression the Okanagan people either died out or are living in caves instead of being a thriving community and culture.

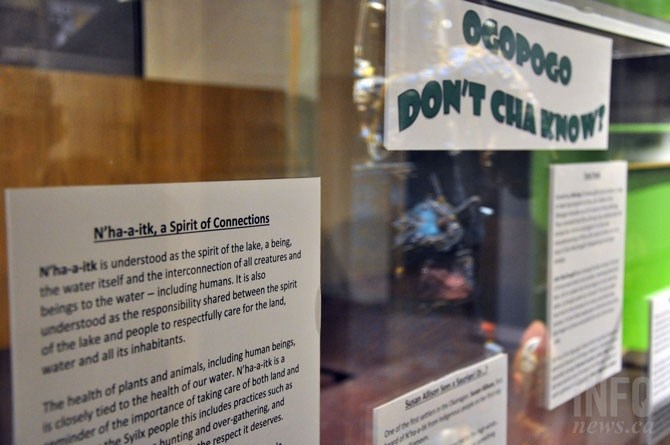

The museum sees a role in helping visitors understand the true history of culturally appropriated symbols like Ogopogo.

(MARSHALL JONES / iNFOnews.ca)

Rather than get defensive, the museum set about changing not only the exhibits but how they thought about them, including subtle biases, curatorial manager Amanda Snyder says.

“Right now, you walk around and read the text, it is clearly written from a settler perspective,” Snyder says. “The texts sort of read like an anthropological study or a textbook rather than letting that community tell their own story.”

To be fair, the heritage museum is hardly alone among museums across the country with flawed depictions of indigenous people and the museum was well ahead of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in recognizing its deficiencies and making changes, though that too may help.

Last year, in its final report, the commission called on Canada’s institutions and its people to, among a great many other things, recognize the atrocities committed against indigenous people. It called on museums in particular to acknowledge these truths and put the facts on display. Reconciliation can’t begin without acknowledgement.

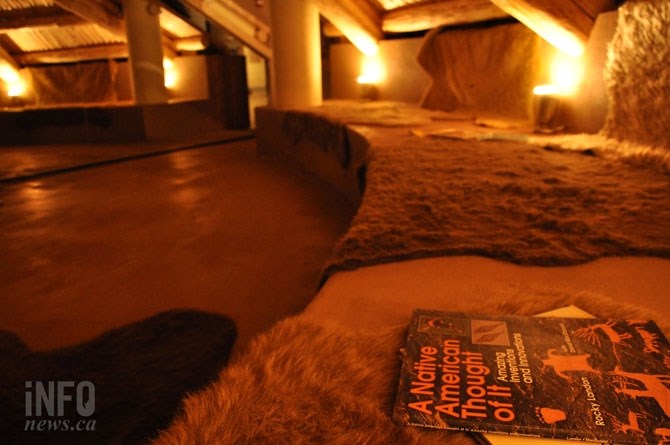

The call to action coincided with a general overhaul for the heritage museum, but Snyder says the team there is up to the challenge. It’s updated many of the exhibits already, including a new, truer representation of a traditional Okanagan winter home and acknowledging the challenges imposed on indigenous populations generally and the Okanagan specifically.

“We want to do the right things as a museum,” Snyder says. “We want to be relevant to the various communities within this community and in doing so we want to engage with respect and on an equal level.”

The museum has worked closely with Westbank First Nation in past, as it sought guidance and interpretation as well as repatriation of local artifacts, but it’s even closer now. Through the process, they've also come to realize the indigenous story is best explained by indigenous people.

And they’re ready for it. The Snecwips Heritage Museum opened in its new location in June 2014, just off Highway 97 by the old Sears store.

“We often direct visitors to see that museum because who better to tell their story than the Snecwips Museum,” she says. “We still want to tell those stories here because of the history here and as part of the broader community. Even new finds, when we get calls now, we send them right over there.”

The inside of the new winter house at the Kelowna Heritage Museum.

(MARSHALL JONES / iNFOnews.ca)

***

The only exhibit at the Snecwips museum that is protected from your touch is a chunk of stone with a figure drawn in red. It was chipped away from its original home, luckily discovered and returned to Westbank First Nation.

It sits on a black display, covered with five sides of glass cube.

The rest of the cultural exhibits, the paintings, carvings, blankets, furs and tools aren’t confined by time or space at all. They're history in the present. The pine needle basket was created by contemporary Secwepemc Nation artist Buffy Lynch much as her ancestors made them. The dugout black cottonwood canoe is in the water almost every year. Some of the artwork was created by former chief Noll Derriksan, who owns the building housing the museum.

Curator Jordan Coble takes a strong stand on how exhibits are displayed. He refuses to call them artifacts.

“The history of me in this space is kinda funny,” he says. “It was my very last year of university, my last class and I had just finished my last exam. (We were) sharing presentations and one of the wonderful people in that classroom shared their presentation on a small museum in Greenwood and how they represented First Nations people. She was talking about how great it was to see that recognition of aboriginal people.

“My first question was ‘how was it represented?’ She said ‘well through artifacts, through rock tools, stone tools and, you know, through old pictures.’ I said ‘well is there any recognition of them still being there?’ She says well no. I said that is the problem with museums and after that I walked out of that class saying ‘I will never work for a museum'.

“I was literally on my way to the car and I got a phone call from Gayle Liman, who was the original curator and heritage officer, asking if I wanted to help out with this museum, the Snecwips Heritage Museum. And I laughed. I was hesitant at first because I had just made the claim that I will never work for a museum.

“Then I realized this was an opportunity. This was meant to be. This was an opportunity to reclaim what museums can do for First Nations people. I said I will help but I will not represent our people as if we are gone, dead and no longer existing. I said we are going to create a living museum, where living artifacts will acknowledge the living spirit within these collection pieces and move forward knowing that we are still here and will be here for a long time.”

Jordan Coble once declared he would never work at a museum but agreed to take on the Sncewips Heritage Museum with a few conditions.

(MARSHALL JONES / iNFOnews.ca)

Coble admits he bears the weight of his own goals for the museum. He understands well the importance for Syilx people to connect with and understand traditional Syilx history, tradition and identity. He also knows culture can’t survive in a glass box. The Interior Salish never built tipis or totem poles or had powwows, but they’ve been variously adopted from their neighbours just like hip hop, Ford trucks or the National Football League.

Culture is alive; the museum is its home.

“I have taken on a lot of responsibility for our culture because that is something that I acknowledge is lacking in (Westbank First Nation) and many of our community members would acknowledge that as well,” he says. “I believe that has to do with things like residential schools, with the misidentification of who we are as Westbank First Nation members.

“I am here to remind people we have always been living in our culture, it’s just changed over the years. And it’s supposed to change. If cultures don’t change they eventually will die off so we need to kind of move with those changes.”

The museum has enormous potential for Westbank First Nation and the entire Syilx nation to reconnect with its own history and has expansion plans of its own.

But the door to the museum is wide open and Coble is eager to share stories with anyone. It’s a must-stop for visitors and neighbours alike to understand the rich history of this land and its people. N’ha-a-itk is far more interesting than Ogopogo. There’s much to learn, no reason to be defensive.

Coble is passionate, knowledgeable, approachable and ready for any questions.

“The tougher conversations are my favourites,” he says. “You get the not so sympathetic questions but then when you are able to explain it to them, they have a better understanding of who you are, that this is, first of all, a safe place to ask those questions in any way they want to word it. I always say it is really tough to offend me, so please just ask before you assume. Don’t just go out into the public with those assumptions.

“Come on in and ask for yourself.”

(MARSHALL JONES / iNFOnews.ca)

News from © iNFOnews, 2021