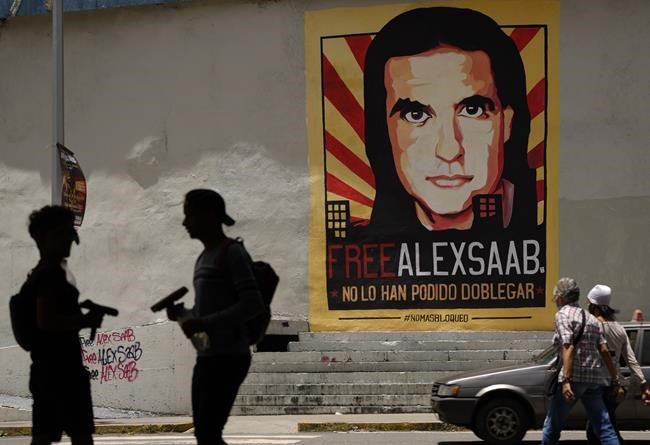

FILE - In this Sept. 9, 2021 file photo, pedestrians walk near a poster asking for the freedom of Colombian businessman and Venezuelan special envoy Alex Saab, and that reads in Spanish "They haven't been able to bend him," in Caracas, Venezuela. Venezuela’s government quietly offered in 2020 to release imprisoned Americans, the so-called Citgo 6 along with two former Green Berets tied to a failed cross border raid, in exchange for the U.S. letting go Saab, a key financier of President Nicolás Maduro, who was extradited to Miami in Oct. 2021. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos, File)

Republished November 10, 2021 - 6:05 PM

Original Publication Date November 10, 2021 - 8:46 AM

MIAMI (AP) — A businessman accused of siphoning off millions in state contracts from Venezuela met secretly with U.S. law enforcement to provide intelligence against Nicolás Maduro’s government prior to being charged in 2019 with money laundering, according to new filings in a related case against a disgraced University of Miami professor.

Bruce Bagley, who prior to his arrest in 2019 had been a top expert on organized crime in Latin America, is set to be sentenced next week in Manhattan federal court on two counts of money laundering tied to nearly $3 million in payments he received from the businessman, Alex Saab.

In a request for leniency, Bagley's attorney argued that his client was told that the payments, the bulk of which he forwarded to an unnamed intermediary's bank account, were to conceal payments to attorneys in the U.S. who accompanied Saab to meetings in which he allegedly provided law enforcement officials intelligence on Venezuela's government.

“It is uncontradicted," attorney Peter Quijano wrote in a heavily-redacted 27-page sentencing memorandum filed Wednesday, that Saab and the intermediary came up with ”this wire-transfer method in order to hide Saab's payments to U.S. attorneys from prying eyes in Venezuela.”

After The Associated Press reported on the meetings, the sentencing memo was deleted from the public docket, on instructions from Judge Jed Rakoff, and then refiled with details of Saab's meetings with U.S. officials redacted.

Saab was extradited last month to the U.S. from Cape Verde following a bitter legal fight that has strained relations between Washington and Caracas.

The U.S. has described Saab as the main conduit for corruption in Venezuela, someone who reaped huge windfall profits from dodgy contracts to import food while millions in the South American nation starved. The Maduro government considers him a diplomat who was “kidnapped” while on a humanitarian mission made more urgent by U.S. sanctions.

It's not clear what was discussed at the meetings, which have not been previously reported, nor whether Saab offered any meaningful assistance or simply used the opportunity to sniff out information about the U.S. probe into his own activities.

David Rivkin, one of Saab’s attorneys, strongly rejected the claim that his client had ever cooperated with American officials as “totally false.”

“At all times, Alex Saab has been a loyal citizen of Venezuela and has conducted all of his activities with the full knowledge and blessing of the government of Venezuela,” said Rivkin.

But Bagley's explanation tracks with the account of three people familiar with the investigation into Saab who said that he met with U.S. federal law enforcement, including agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration, on multiple occasions in Colombia and Europe prior to being charged in 2019. The three individuals spoke to The Associated Press on the condition of anonymity to discuss the meetings.

U.S. prosecutors and investigators frequently meet with criminal suspects outside the U.S. when they are seeking to recruit them to provide assistance against a bigger target in exchange for promises of confidentiality and the possibility of leniency.

But any meetings attended by Saab would have entailed major risks for the Colombian-born businessman given his close ties to Venezuela's ruling elite, including Maduro's own family.

Federal prosecutors in Miami indicted Saab in 2019 on money-laundering charges connected to an alleged bribery scheme that pocketed more than $350 million from a low-income housing project for the Venezuelan government.

Separately, Saab was sanctioned by the previous Trump administration for allegedly utilizing a network of shell companies spanning the globe — in the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Hong Kong, Panama, Colombia and Mexico — to hide huge profits from no-bid, overvalued food contracts obtained through bribes and kickbacks. Several of his associates, including a longtime business partner and a pro-government former governor, were indicted last month for involvement in the alleged scheme.

Some of Saab’s contracts were obtained by paying bribes to the adult children of Venezuelan first lady Cilia Flores, the Trump administration alleged when it announced the sanctions. Commonly known in Venezuela as “Los Chamos,” slang for “the kids,” the three — children of Flores from a previous relationship — have themselves been under investigation by prosecutors in Miami for several years.

The U.S. attorney’s office in Miami, which is handling the investigation into Saab, declined to comment.

Rivkin said Saab never met Bagley or ever worked with him in any capacity. However, that would appear to contradict what Saab told the newspaper El Espectador in Colombia. In an April interview, Saab said that he was saddened by Bagley’s legal problems and that the University of Miami professor had been recommended to him as an expert who could help defuse what he saw as a politically motivated money laundering investigation.

Whatever their relationship, Bagley's role in Saab's alleged graft network appears to have been relatively minor.

Saab initially hired Bagley to help get a student visa for his son and later sought his advice on investments in Guatemala, according to prosecutors. Then starting around November 2017, Bagley began receiving monthly deposits of approximately $200,000 from a purported food company based in the United Arab Emirates. Additional funds were wired from an account in Switzerland.

He then transferred 90% of the money into the accounts controlled by an informant in the belief they would be forwarded to Saab's U.S. attorneys. But Bagley kept a 10% commission for himself and continued to accept the cash even after one of his accounts was closed for suspicious activity. In total he received nearly $3 million, according to prosecutors.

The informant's name is redacted from Wednesday's sentencing memorandum. But in court last year to plead guilty, Bagley identified him as Jorge Luis Hernandez, a longtime U.S. informant in anti-narcotics cases from his native Colombia better known by his nickname Boli. He’s also served as a broker connecting narcos with American defense attorneys.

Bagley, an expert on Colombia’s criminal underworld, had provided testimony in support of Hernandez when he applied for asylum in the U.S. arguing he would be killed if he were deported to Colombia, where he had ties with right-wing paramilitary groups who then dominated drug trafficking along the the Caribbean coast.

Over the years, Hernandez proposed to Bagley lucrative business proposals to provide consulting services to top politicians from around Latin America, including a Colombian governor, Kiko Gomez, with ties to far-right militias and an unnamed presidential candidate from Paraguay.

On one occasion in 2019, Bagley traveled to New York to meet with Luis Dominguez Trujillo, a presidential hopeful from the Dominican Republic and grandson of the Caribbean island's former dictator, Rafael Trujillo. Unbeknownst to Bagley at the time, the meeting was being surveilled at the direction of New York prosecutors.

“But Dr. Bagley, who was not motivated by the lure of a great deal of money, rejected (Boli's) job offer to work for a seemingly shady politician, thus defeating that particular attempt of (Boli) to deliver a defendant,” Quijano wrote.

When Bagley did finally yield to Hernandez's entreaties, he thought it was to protect Saab from possible retaliation by powerful officials in Venezuela if they were to suspect he was cooperating with the United States, Bagley's attorney said.

“The concern was not with the United States becoming aware of these payments but individuals in and the government of Venezuela discovering them," Quijano wrote. “Saab agreed with (Boli) that their financial connection would make many important people in Venezuela nervous, considering his close ties to some of the government officials there. For the same reason, Saab could not pay his attorneys in the United States directly.”

However, prosecutors contend that Bagley knew the funds were the product of corruption and state funds “ultimately being taken from some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the world.”

“Yes. It is corruption,” the professor told Hernandez in one recorded conversation from a December 2018 meeting, adding that he knew Saab was deeply involved in the importation of food on behalf of the Maduro government. “They have imported the worse quality products with inflated prices, and they have filled their pockets with money.”

Prosecutors argue that Bagley in statements to law enforcement has yet to show real remorse or fully acknowledge his role in serious criminal conduct. They nonetheless are urging Judge Jed Rakoff to impose a lighter jail sentence than the recommended 46 to 57 month range due to Bagley's age — he's 75 — and deteriorating health.

Bagley retired from the University of Miami last year after a long career as an international studies professor. A top expert on money laundering and organized crime, he wrote numerous books on the subject, testified before Congress and was regularly hired as an expert witness in court. As part of his request for leniency, lawyers provided the names of 39 individuals on whose behalf he testified as part of their asylum requests or immigration proceedings.

___

Joshua Goodman on Twitter: @APJoshGoodman

News from © The Associated Press, 2021