Wildfire has infiltrated a Brazilian state park known for its population of jaguars;

Republished September 10, 2020 - 2:45 PM

Original Publication Date September 10, 2020 - 10:36 AM

RIO DE JANEIRO - Wildfire has infiltrated a Brazilian state park known for its population of jaguars as firefighters, environmentalists and ranchers in the world’s largest tropical wetlands region struggle to smother record blazes.

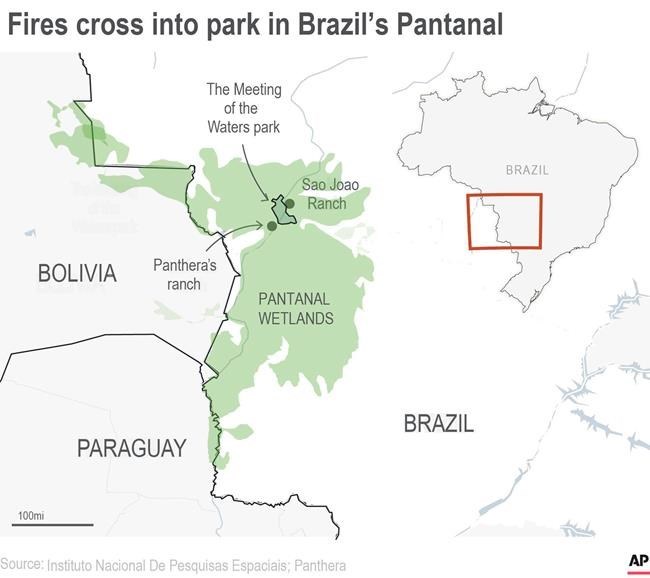

The fire had surrounded the Encontro das Aguas (Meeting of the Waters) park in the Pantanal, located at the border of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul states, but for a time rivers helped keep the blazes at bay. Then wind carried sparks into the park and flames have been wreaking destruction for over a week.

There is little outlook for any near-term help from rainfall, said the Mato Grosso firefighters’ spokeswoman, Lt. Col. Sheila Sebalhos.

“The forecast isn’t good,” Sebalhos said by phone from the state capital of Cuiaba, after spending weeks in the fire zone. “High speeds of those winds that change direction many times throughout the day are favouring the rapid spread (of fire).”

Some 200 jaguars have already suffered injury, death or displacement because of the fires, according to Panthera, an international wild cat conservation organization.

The Pantanal is home to thousands of plant and animal species, including 159 mammals, and it abounds with jaguars, according to environmental group WWF. During the wet season, rivers overflow their banks and make most of the region accessible only by boat and plane. In the dry season, wildlife enthusiasts flock to see the normally furtive felines lounging on riverbanks, along with macaws, caiman and capybaras.

What’s unique about the Meeting of the Waters park, which covers more than 1,000 square kilometres (over 400 square miles), is that the jaguars are habituated to human observation. They have been a top eco-tourism draw for more than 15 years, according to Fernando Tortato, a conservation scientist for Panthera, which owns a neighbouring property where jaguars can range.

On Panthera’s land, even before fires started raging, employees and volunteers used two earth-movers to create a firebreak around the property’s perimeter. Since blazes arrived, the group has tracked the shifting winds to open new firebreaks and head off the devastation.

“We prepare the team, a truck with a water pump, fire swatters and backpack water pumps so that, in case the fire jumps that barrier, we can combat it,” Tortato said by phone from Panthera's land. “It’s the only strategy that has managed to resolve the fire, in some situations.”

Despite tireless efforts, some 15% of Panthera’s sprawling property has been consumed by fire, he said.

The Pantanal is located mostly in Brazil and stretches into Bolivia and Paraguay. Whereas ranchers in the Amazon often use fire to clear brush and open new pasture, fires in the Pantanal are often unintentional, set by locals and then spiraling out of control due to climate conditions, according to Felipe Dias, executive director of environmental group SOS Pantanal. One cause of this year's Pantanal fires was the use of burning roots to smoke wild bees out of their hives to extract honey, said Sebalhos.

This year has been the Pantanal's driest in 47 years, and rain isn't expected until October, Dias said. Only rain can truly extinguish the wildfire, he added.

“There’s a climate problem. The rains happen in a concentrated way and then 30, 40, 50 days go by without rain,” Dias said. “The Pantanal is a flood plain; the soil should be soaked.”

The number of fires the Pantanal has seen so far this year already exceeds the annual totals for every year on record, stretching back to 1998, and is more than double the annual average for the prior 10 years, according to data from the government’s space agency, which uses satellites to count the blazes. More than 10% of the area has been consumed by fire this year, according to WWF and SOS Pantanal.

President Jair Bolsonaro, a staunch supporter of development in Brazil's hinterland, bowed to international pressure and issued a decree in July prohibiting the use of fire in the Amazon and Pantanal regions throughout this year’s dry season. In practice, it’s done little to slow the burn, with scant enforcement of his moratorium, environmentalists say. Brazil's environment ministry didn't respond to Associated Press requests for comment about its oversight.

Brazil's government dispatched 173 members of the armed forces to Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul states, along with 139 firefighters from the Chico Mendes Institute, the arm of the environment ministry that manages federal parks, according to the defence ministry. Tallies provided by state firefighter corps indicate the numbers might be significantly fewer. Bolsonaro has chalked up difficulties in fighting the Pantanal fires to the size of the affected area.

“I started to suffer criticism because the Pantanal is on fire,” the president said Aug. 20 in a live broadcast on Facebook. He noted the vastness of the Pantanal, saying: “You can imagine the difficulty of fighting the fire in that area.”

Unlike the Amazon that has a slew of federally protected areas, some 95% of the Pantanal is privately owned, according to WWF and SOS Pantanal. The Pantanal land can also regenerate quickly.

There are about 2,000 jaguars in an area that is called the Jaguar Conservation Unit, which is half of the Pantanal, according to Panthera.

Between 80% to 90% of Meeting of the Waters is susceptible to fire, with the remaining rivers, brooks and swamps currently serving as refuges for fauna, Tortato said. The most vulnerable creatures are baby birds, reptiles and amphibians, whereas larger mammals have greater ability to flee and survive.

Col. Paulo Barroso, who is co-ordinating animal rescue for Mato Grosso state’s environment secretariat, hopes animals will escape to the private Sao Joao ranch adjacent to the park. He told the AP by phone from the location that his strategy is to start making firebreaks Thursday to guide animals to an artificial safe haven.

“We’re trying to defend this space (Meeting of the Waters) against the threat from some fires, it’s just that there are fires coming from all sides,” Barroso said. “The fire fronts are closing in on the park and the idea is to create an island to receive those animals and protect them.”

___

Associated Press writer David Biller reported this story from from Massachusetts and AP writer Marcelo de Sousa reported in Rio de Janeiro. Videojournalist Tatiana Pollastri in Sao Paulo contributed to this report.

News from © The Associated Press, 2020