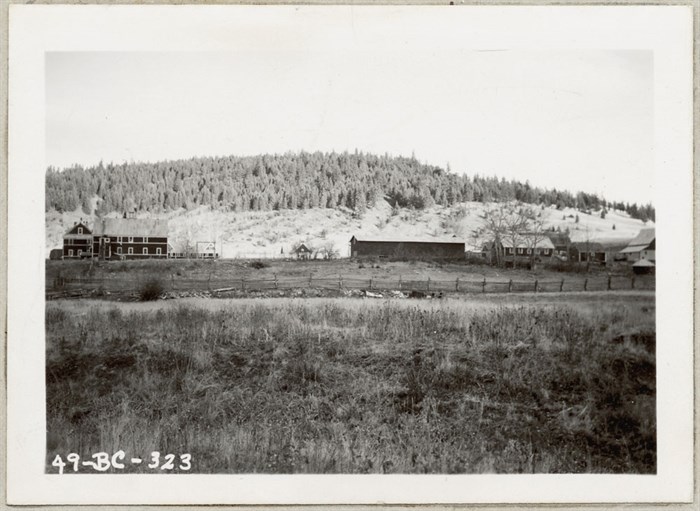

Cariboo Indian Residential School, distant view of school buildings and grounds, Williams Lake, 1949

Image Credit: Library Archives of Canada

May 30, 2021 - 6:30 PM

When Laurine Vilac was just six years old she was dropped off at a residential school in William's Lake.

She remembers her mom and dad holding her hands and she remembers them leaving her there without explaining why.

"I didn't understand what was happening, “Vilac said. “I didn't know why they left me there."

Now 85 years old, living in Kamloops, the Canim Lake Band woman shared her painful memories in the peace of her small apartment with her teenage grandson beside her, holding her hand.

"There were always lineups,” Vilac said. “It seems we lined up for everything. The first thing the nuns did was line us all up and cut off our hair. They dumped anti-bug powder on our heads regardless of whether we needed it or not.

We were often told that if we misbehaved we would not get to see our parents for summer vacation. And if we lost our tam, a headpiece worn for church, we would have to kneel on a cold floor for long periods of time. Some kids would fall asleep. I still have dreams of them, finding them curled up in their nighties on the floor the next morning."

Laurine spent six years at her first residential school and four more at a second one before she went on to college to be a nurse. The years away from her family were detrimental.

"When I went back for summers my mom didn't know me anymore,” Vilac said.

“She didn't know how to talk to me. We didn't have a relationship anymore. Every September we were gathered up and transported back to the school in cattle cars. We would arrive covered in dirt, wiping our eyes clean. Some people question why some of us are messed up after growing up like this. I don't understand that. We were removed from our parents. We were traumatized."

Bad things took place at those schools and we had no one to tell. I remember some girls ran away, trying to get home. They gave up and returned to the school, cold and asking to come in. The nuns locked them out and the next morning they found the body of a little girl who had frozen to death in the night. These are the kinds of things I still have nightmares about."

Laurine finally found her own home when she married and had children. She raised three of her sons and three of her nephews and was married for more than 50 years.

Sadly, her husband passed away seven years ago after a battle with cancer.

Laurine and her sons have spent hours donating their time to others. Her late son, David, knew every street entrenched person by their first name.

"It was kind of a running joke,” Vilac said. “David would come to my house to shop when someone he knew needed something. Of course, I didn't mind. I knew he was helping someone in need. I have taught my kids to respect others. I have taught them we are no better than anyone else."

This isn't the first time Laurine has shared her story. In the 1990s she took to a podium outside the Supreme Court in Vancouver. She talked about residential schools as part of an attempt to get the federal government to compensate First Nations people for damage done.

Christian churches and the federal government launched the residential schools in the 1880s and kept them going for more than a century. Their aim was to convert and assimilate Indigenous children, and in the process, generations suffered widespread physical and sexual abuse at the institutions. St. Joseph’s Mission in Williams Lake operated from 1890 to 1981.

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, about 150,000 Indigenous children were removed from their homes and forced to attend residential schools in Canada.

The centre estimates the number of children identified by name, as well as unnamed in death records, is about 4,200.

The first schools opened in the 1880s and the last residential school closed in Punnichy, Sask., in 1996.

To contact a reporter for this story email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2021