The Revelstoke Dam, built two decades after the Columbia River Treaty, is just one of hundreds of hydroelectric facilities along the 2,000-kilometre Columbia River.

Image Credit: Aaron Hemens, Local Journalism Initiative

January 18, 2025 - 7:00 PM

With Donald Trump preparing to take office, concerns swirled at a recent public meeting about his presidency’s potential impact on efforts to modernize the cross-border Columbia River Treaty.

There is still no timeline in sight after years-long negotiations to update the international deal that First Nations were excluded from 61 years ago.

Some at a treaty information session last month expressed fears for the agreement as a whole, which oversees the heavily dammed waterway between the U.S. and Canada.

On Dec. 19, the Government of B.C. hosted the virtual session for residents around the river’s basin to hear updates from officials and ask questions about treaty modernization efforts.

More than 100 people tuned in, inquiring about everything from how flood risk would be managed to what would happen if no new deal is reached.

But there were also a number of questions related to what Trump’s administration, set to assume power on Jan. 20, might have on the treaty.

Since winning the 2024 presidential election two months ago, Trump has repeatedly floated the idea of making Canada a 51st state of the U.S.; on Tuesday, he suggested using “economic force” to “get rid of that artificially drawn line” between the countries.

One person attending the treaty information session pointed to how Trump said he can “turn the faucet” and have water trickle down from Canada into California by way of B.C.

They then asked if there is a plan in place to protect the water, and if there are any internal concerns about Trump delaying or stopping efforts to update the treaty.

“We’ve been at this with the previous Trump administration, the Biden administration and potentially with a new Trump administration,” replied Stephen Gluck, the lead negotiator for Canada in treaty modernization process.

“The work we’ve done with the U.S. essentially hasn’t changed — it’s been going forward. We continue the work we do, no matter who’s in power in the U.S.”

Provincial Minister of Energy and Climate Solutions Adrian Dix, whose responsibilities include the Columbia River treaty, said negotiators “can’t be distracted” by the political rhetoric.

“I will say though that this modernized treaty is significantly in the interests of everyone on both sides of the border,” Dix said. “A lot of the voices in favour of this treaty and revised treaty are from all parts of the political spectrum. I’m always optimistic.”

Six years of negotiations helped establish an agreement-in-principle (AIP) last July to modernize the Columbia River Treaty, but Gluck said that there is still no timeline for when an updated treaty might come into effect, only noting that the goal is to get to that stage in the near future.

He also highlighted that the treaty itself can be terminated by either country with 10 years notice.

“Along with treaty drafting — if and when we get there — there will be approval processes necessary in both countries,” said Gluck at the meeting.

“At this point, there’s no timeline for this, and will need an acceptable drafted treaty text before any of this happens.”

Dix, however, did note that “enormous efforts” were made in December to draft, prepare and work on a modernized treaty language that reflects the AIP.

“While we don’t have a final treaty language, significant efforts have been made,” said Dix.

When asked what would happen should the two countries fail in modernizing the treaty, the province’s lead negotiator, Kathy Eichenberger, warned that the treaty’s operations will remain stuck in the 20th century.

“Things have changed so much,” she said. “The environment wasn’t considered in 1961; First Nations weren’t involved; communities weren’t consulted; climate change was on very few people’s thoughts; and adaptive management was not something that was incorporated into the treaty.

“Now we know we need to tackle these very important issues.”

‘One of the largest infringements on the syilx Okanagan territory’

The 61-year-old international deal between Canada and the “U.S.” governs the waters of the Columbia River, which crosses the border from its headwaters near Trail, B.C.

Initially, the treaty’s two main purposes were to prevent flooding in cities down-river, and to provide reliable hydroelectric power from hundreds of dams along the cross-border waterway.

As a result of the treaty, there are now 470 dams along the 2,000-kilometre river and its tributaries, according to the Columbia Basin Trust.

Prior to colonization, the river was once one of the greatest salmon-producing river systems in the world. But hundreds of dams built along its course — such as the Grand Coulee Dam in “Washington” — have blocked salmon from returning to Canada, as noted by the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA).

Salmon are a species that have been a key cultural cornerstone and food source for the syilx Okanagan and other Indigenous nations in the region for thousands of years.

The ONA has said that the original Columbia River Treaty has been “one of the largest infringements on the syilx Okanagan territory,” noting that it has “profound and lasting impacts” on syilx people, their title and rights, and way of life.

In 1961, the original treaty-makers from the two colonial governments excluded Indigenous voices from having a say in crafting the document, which was ultimately imposed upon all people living in the Columbia River Basin region.

Not only were Indigenous peoples ignored, but the well-being of the land, the salmon, other living creatures, and ecological functions weren’t given consideration in the original treaty, say multiple sources in the syilx Okanagan Nation.

“Three dams were built in Canada that flooded out hundreds of thousands of hectares, and destroyed hundreds of thousands of species. It inundated sacred sites and burial sites, and commenced a lot of damage,” said Jay Johnson, chief negotiator and senior policy advisor to the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA)’s Chiefs Executive Council, shortly after the AIP was reached.

The Secwépemc, syilx Okanagan and Ktunaxa Nations all pushed to have their voices heard at the table when talks between the U.S. and Canada began to modernize the treaty in 2018.

Through the Bringing the Salmon Home initiative, the three nations have spent years developing long-term plans to re-introduce salmon into the Upper Columbia River. In August, they brought sockeye salmon back to Arrow Lakes, which is part of the river system — more than 80 years after the species was blocked from returning to spawn.

Lance Thomas, with the Ktunaxa Nation’s Guardian program, releases an acoustically tagged adult sockeye salmon into the Arrow Lakes on Aug. 30, 2024.

Image Credit: Aaron Hemens, Local Journalism Initiative

While they remain legal observers in treaty modernization discussions, the three nations played crucial roles in helping to inform Canada and B.C. in their position on the AIP, particularly with provisions to support salmon and ecological health.

Although the AIP is not legally binding, it offers a framework for the two countries to update the decades-old treaty.

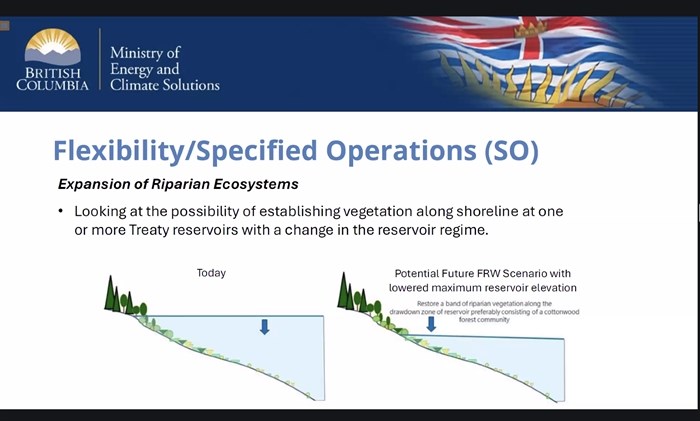

During the public information session, Indigenous and non-Indigenous officials went into detail about one component of the AIP, known as “Canadian flexibility,” also referred to as “specified operations.” That part of the treaty would work to address the original treaty’s impact on Indigenous cultural values as well as on riparian ecosystems — wetland habitats on the banks of waterways.

The Indigenous-led effort could see roughly 19 trillion litres used for power generation at one or more treaty reservoirs — Arrow Lakes, Kinbasket or Duncan — reduced by up to one-third to help create “more naturalized” flows for fish populations.

The focus is not power generation, but rather to restore shoreline vegetation, repair riparian ecosystems, wetlands and floodplains.

The nations’ ultimate goal is to improve the ecological functions of the basin, and create greater access to Indigenous cultural practices.

A presentation slide showing the details of the AIP’s ‘Canadian Flexibility’ component, or specified operations, which if implemented would reduce reservoir water levels to help restore ecosystems.

Image Credit: Photo courtesy Government of B.C.

“It’s something that I’m very proud of, the achievement that we’ve come so far,” said Troy Hunter, the lead negotiator for the Ktunaxa Nation. “We look forward to implementing that.”

Hunter noted that central to the specified operations of reducing power generation water levels are to help to replenish salmon populations, as well as honouring seasonal cultural activities.

Workshops involving the three nations, at which Elders and knowledge-keepers provided guidance, helped inform this approach.

“We’re making progress. It’s not easy work trying to explain this to our Elders,” said Hunter.

“How do we take this desire for making the river a better place for our cultural activities, and bring it to this Columbia River Treaty?”

Johnson compared Indigenous efforts to “rectify” mistakes of the treaty’s past to the importance of a stool’s legs for stability.

He said the ONA is looking forward to a finished treaty that includes the functions of ecosystems as a “particularly important leg of the stool, along with flood control and power generation,” he said.

“Our work has evolved to really help ensure that the interests of our communities, the interest of basin residents, the interests of the ecosystem and environment are included in a pretty profoundly important way.”

— This article was originally published by IndigiNews.

News from © iNFOnews, 2025