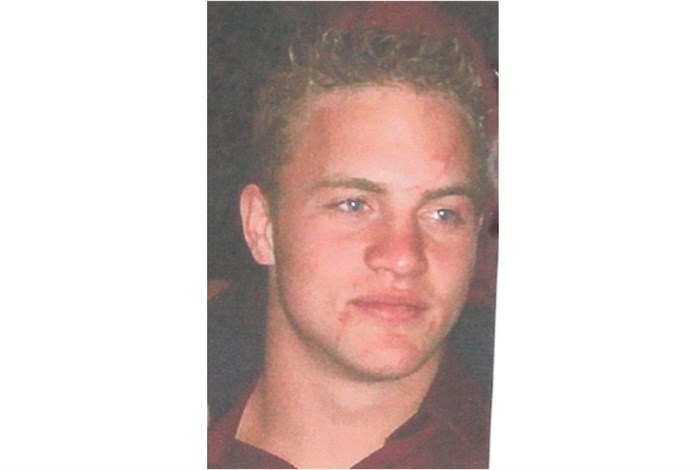

William James Strande, 31, died on Nov. 19, 2020, less than 24 hours after being admitted to the Kamloops prison after allegedly breaching of his parole conditions. He was scheduled to be released on Feb. 27 of this year.

Image Credit: SUBMITTED

March 12, 2021 - 7:00 PM

The family of a Merritt man who died at Kamloops Regional Correctional Centre last November is seeking answers months after his apparent suicide.

William James Strande, 31, died on Nov. 19, 2020, less than 24 hours after being admitted to the Kamloops prison after allegedly breaching of his parole conditions. He was scheduled to be released on Feb. 27 of this year.

Doug Mikalishen and wife Donna are aunt and uncle to Strande and raised him. They have tried getting more details from BC Corrections about their nephew’s death, but have thus far been stymied.

The Mikalishens said they were told their nephew hanged himself in the prison with a plastic bag. They said they received a call on the afternoon of Nov. 19 from KRCC’s deputy warden, who said Strande was in hospital and on life support. Days later, the family said their goodbyes and Strande was taken off life support and died.

Four months since Strande’s death, Doug said he is frustrated because he still has questions regarding how his nephew died. He said as he understands it, as the next of kin, he is supposed to be kept abreast of the investigation into the death.

“And they’re not,” Mikalishen said. “Maybe the investigation’s over, I don’t know.”

Strande, who Mikalishen said was a drug runner, had been living at his cousin’s house in Merritt since Oct. 22, when he was released from Mountain Institution in Agassiz after serving time for a breach of his parole from Edmonton.

Mikalishen said his nephew was on suicide watch during his stay in the Agassiz prison.

A Correctional Service Canada report dated Sept. 13, 2020, noted Strande had “been on high watch for attempting suicide” for three days. “Strande had cut his wrist and was required to attend outside hospital for stitches,” the report stated, adding that he “has a history of self-harming behaviour.”

Mikalishen believes the justice system ignored Strande’s mental-health issues, suggesting his nephew’s parole officer would have been aware Strande had been on suicide watch when he was re-incarcerated in Kamloops on Nov. 18 for refusing to give a urine test.

Given the state of his nephew’s mental health, Mikalishen feels Strande should never have been brought back to jail.

A spokesperson for BC Corrections confirmed a death occurred from an incident at Kamloops Regional Correctional Centre, but did not refer to Strande by name. An emailed statement reads that while privacy laws prevent the release of specific details, BC Corrections investigates and completes an internal review of all circumstances that result in a death in custody.

“We understand that the BC Coroners Service is also investigating, as they do in all unexpected and/or unnatural deaths in B.C., to determine how, where, when and by what means the individual came to their death. Only the BC Coroners office can disclose these details,” BC Correction’s public affairs officer Hope Latham said in an email response.

She added that additional questions regarding health care for individuals in custody should be directed to the Provincial Health Services Authority’s correctional health services team.

The B.C. Coroners Service has not yet decided whether to call an inquest. The investigation remains active and, per the Coroners Act, the agency is unable to disclose any information during an open investigation.

In prison, Strande detailed his thoughts on mental health, writing in a letter dated Oct. 12, 2020 — which was included in his obituary — that “a cry for help in prison can take a year of paperwork. A failed suicide attempt is met with punishment and alienated embarrassment.”

Strande also apologized to anyone he hurt or offended in the past and cautioned that people “don’t assume jail or prison will fix your child’s actions. Tough love is proven to make things worse during a mental-health crisis.”

Strande came to live with his Aunt Donna and Uncle Doug on their property in Lower Nicola at the age of eight. His father often worked out of town and he had recently lost his mother, Candace Venuti, to cancer.

Moving to Edmonton at 19, Strande secured a job as a nightclub bouncer and began his descent into the drug trade, according to reports by the Correctional Service Canada and the Parole Board of Canada in which there are numerous references to Strande’s serious mental-health issues. He took medication for anxiety, depression, PTSD and ADHD and was often paranoid.

A Dec. 20, 2019, Correctional Service community assessment noted that “Strande has mental-health issues which make full-time regular work difficult for him.” It said his Edmonton psychiatrist supported his application for a disability pension.

In one report dated Feb. 2, 2020, a correctional officer noted Strande may not have been in his right state of mind. Prior to being transferred to Mountain Institution in Agassiz, Strande was in Matsqui Institution in Abbotsford on April 22, 2020, where he was found in his cell with a self-inflicted cut to his ear and a piece of his ear in his mouth.

On April 28, 2020, the parole board decided to suspend his statutory release in part because he had no confirmed employment, despite earlier correctional reports indicating he was offered work at a family business and qualified for a disability pension due to his mental illness. In July 2020, he lost an appeal on a technicality.

Details such as these have frustrated the Mikalishens, who point to them as examples of the justice system failing to help inmates returning to society.

— With files from the Vancouver Sun

— This story was originally published by Kamloops This Week.

News from © iNFOnews, 2021