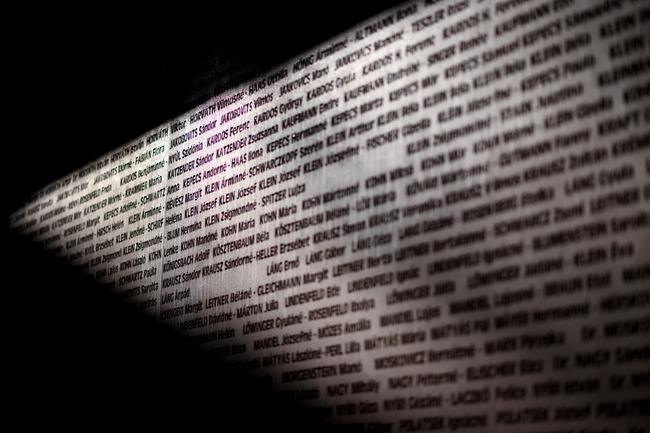

Sunlight illuminates the names of the local holocaust victims inscribed on the Wall of Remembrance at the Pasti Street Orthodox Synagogue in Debrecen, northeastern Hungary, Monday, Jan. 27, 2025, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day. (Zsolt Czegledi/MTI via AP)

Republished January 29, 2025 - 3:17 AM

Original Publication Date January 27, 2025 - 6:16 AM

BUDAPEST, Hungary (AP) — On the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp, in which nearly half a million Hungarian Jews lost their lives at the hands of the Nazis, Tamás Léderer still can't shake the sense that the world hasn't learned from the horrors of the 20th century.

Born in Budapest in 1938, Léderer, unlike most of Hungary's Jewish population, survived the Holocaust and evaded deportation to German camps by hiding in basements in Hungary's capital. His parents, he said, ripped the mandatory yellow star from his clothing to conceal the fact that he was Jewish.

As the world observes International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Monday, 80 years after the Nazis' most notorious death camp at Auschwitz was liberated by the Soviet Red Army on Jan. 27, 1945, Léderer, 87, says the risk of hate-fueled violence against Jews and other groups continues to unsettle him.

“I must not forget," he said of the fate of the some 565,000 Hungarian Jews that perished in the Holocaust, the mass murder of Jews and other groups before and during World War II. "In my subconscious, I can never get over the possibility that a six-pointed star could be placed on my gate again at any moment. It is always in my mind.”

The Nazis killed some 6 million European Jews during the Holocaust — nearly 10% of them from Hungarian territories. An estimated 1.1 million people, mostly Jews, were killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau, some 435,000 of them Hungarians, more than any other nationality.

Tamás Vero, a prominent rabbi in Budapest, lost many of his family members in the Holocaust. His grandmother, who returned alive from Auschwitz, once told him that she thanked God that he'd become a rabbi so he could ensure the genocide would never be forgotten.

“We carry in our genes what our grandparents' or our parents’ generation went through,” he told The Associated Press. “I think that in order for us to happily observe Jewish holidays or to have Jewishness in our homes, what they experienced must remain a fresh memory, and that memory has to be part of our lives.”

At the outbreak of World War II, Hungary, then a kingdom, joined with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to become an ally of the Axis powers. Hungary’s leader, Regent Miklós Horthy, pursued an irredentist agenda which sought to regain territories Hungary had lost after World War I. Under Horthy, Hungary instituted Europe’s first anti-Jewish laws in 1920.

Believing that Nazi Germany could help restore those lost territories in what are today Croatia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Ukraine, Horthy cooperated with Adolf Hitler throughout the war. However, despite existing anti-Jewish laws, he resisted German demands to deport Hungary’s large Jewish population.

But, fearing Horthy would defect to join the Allies, Hitler ordered the invasion of Hungary in March 1944, and the mass deportations began.

In less than two months between March and May of that year, some 435,000 Hungarian Jews, primarily from countryside cities and villages, were deported to Auschwitz in Nazi-occupied Poland, most of whom were sent to gas chambers on their arrival. As the war approached its end, thousands of others were murdered by Hungary's own fascist Arrow Cross party, whose death squads shot Jews en masse into the Danube River in Budapest.

On Monday, Vero, the rabbi, and others gathered at the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest to observe International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Vero led attendees, some of whom were Holocaust survivors, in a prayer. The center's director, Dr. András Zima, called Auschwitz "the largest Hungarian mass-grave.”

Vero believes that for Jews, preserving the memory of the Holocaust is a way to "commit ourselves to showing the world that, learning from the events of the past, we will not allow anything similar to happen to anyone else.”

But Léderer, who works as an artist from his home outside Budapest, said he believes Hungarian society “refuses to face its past,” and that Hungarian collaboration with the Nazis remains an unresolved mark on the country's consciousness.

“It’s just a matter of time before we get to a moment where people think the time has come to hate someone again,” he said.

News from © The Associated Press, 2025