Man who would later kill Manitoba girl Phoenix Sinclair was deemed high-risk

December 19, 2012 - 11:50 AM

WINNIPEG - Social workers were given a clear warning about Karl McKay's propensity for violence years before he brutally beat young Phoenix Sinclair to death, the inquiry into the girl's killing was told Wednesday.

McKay already had a long history of assaults and domestic violence when he met with his probation officer in April 1999. It was a meeting that the officer said left her scared.

"I certainly felt that day that he was a very angry person and that my safety was at risk, and it wouldn't be safe for one particular individual to meet with him (alone) in the future," Miriam Browne testified Wednesday.

"It was quite possible that he might become violent in the office. I felt physically intimidated by Mr. McKay. That was a very unusual circumstance, I will say."

Two days after the meeting, Browne wrote to the social worker who was dealing with McKay's then-common law partner. She warned the worker of her serious concerns for the safety of McKay's partner and their two children, who would be made permanent wards of the state in 2000.

Despite that letter, and many other warnings about McKay, he would slip under the radar into the life of Phoenix Sinclair in 2004. He had started a relationship with Phoenix's mother, Samantha Kematch. The couple neglected and abused the girl, eventually beating her to death and burying her near a dump on the Fisher River First Nation north of Winnipeg.

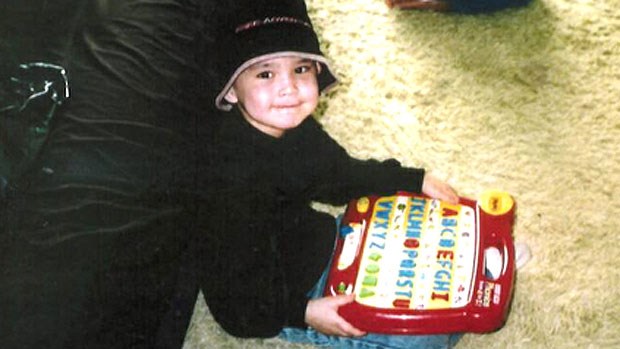

The inquiry is examining how child welfare failed to protect Phoenix, who spent most of her five years bouncing between foster care, her parents, and the homes of family friends. Her death went undetected for nine months.

Phoenix was taken from her parents, Kematch and Steve Sinclair, days after her birth in April 2000. The couple had troubled, violent pasts and was unprepared to care for her, but social workers repeatedly worked toward reuniting the family.

In April 2004, Kematch took Phoenix from friends who were caring for the girl. The inquiry was told earlier that when one social worker went to Kematch's home to check on the girl, a man who identified himself as "Wes" answered the door and said Kematch and Phoenix had gone out. McKay's middle name is Wesley.

The social worker didn't ask the man for his last name and didn't probe any further.

Had she done so and run a background check in the child welfare central information system, she would have turned up a file on McKay that included a long list of documents warning he was a violent, dangerous man.

The file, which has been tabled at the inquiry, includes Browne's 1999 letter which said McKay had repeatedly beaten and bruised his former partner. A report from another social worker said McKay had once taken the supporting leg off a bathroom sink and beaten his former partner with it. Another, earlier report said McKay had broken his partner's nose.

According to an internal review of the case, done by the Winnipeg Child and Family Services agency in 2006 but only made public for the inquiry, McKay would remain under the radar until Kematch gave birth to another child.

"The status of the relationship was further clarified in December when Samantha gave birth to her fourth child and Karl Wes McKay was identified as the father and as Samantha's common law partner," the review states.

"Karl Wesley McKay is listed in (the central information system) and is attached to three other families. If this information would have been accessed, it would have presented some concerning information in relation to family violence issues."

The same review found a series of mistakes that caused Phoenix to fall through the cracks of child welfare. Social workers frequently lost track of who was caring for the girl. They also failed to enforce conditions on her parents, such as alcohol treatment for her biological father and a psychological assessment for Kematch.

Next month, the inquiry will delve into what happened in the final months of Phoenix's life. According to the trial that saw Kematch and McKay convicted of first-degree murder, a social worker went to check on Phoenix but was told she was sleeping and left.

The family moved in 2005 from a Winnipeg apartment to a house on the Fisher River First Nation. There, Phoenix was beaten, starved, forced to eat her own vomit and shot with a BB gun. Other kids in the home were treated well.

After her death, Kematch and McKay continued to claim welfare benefits with Phoenix listed as a dependent. In 2006, Police found Phoenix's body after receiving a call from a relative.

News from © The Canadian Press, 2012