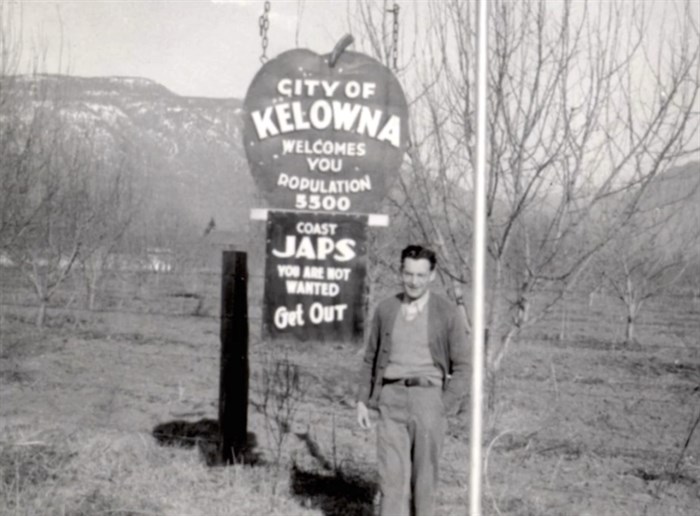

A screenshot of a photo of the sign posted by the Junior Board of Trade in Kelowna from Jeff Chiba Stearns' documentary "One Big Hapa Family".

Image Credit: Jeff Chiba Stearns

November 25, 2024 - 7:00 AM

Photos of this infamous sign have been published and posted numerous times over the last 80 years, but the story behind it has been elusive.

The sign reads, “coast Japs you are not wanted get out”.

Jeff Chiba Stearns is a Japanese-Canadian filmmaker from Kelowna who made a documentary called “One Big Hapa Family” back in 2010 about interracial marriage, his family’s history, and B.C.’s Japanese-Canadian community.

Stearns recalls a photograph of the sign that was on his grandfather’s wall when he was a kid. He said a reporter from the Kelowna Daily Courier printed it out and photographed his grandfather with the sign for an article decades ago.

“That sign has always been part of my collective memory because of the fact that I grew up seeing it. My grandpa just had it sitting up against the wall,” he said. “It was one of those things that I grew up with kind of thinking like, ‘What is that? Why is there a distinction between coastal Japanese as opposed to these local Japanese?”

While Stearns was researching for his documentary he pored through old newspaper articles about anti-Japanese hatred during the Second World War. The Kelowna Museum Archives had a photo of the sign, but it didn’t know the context that Stearns discovered while making his documentary.

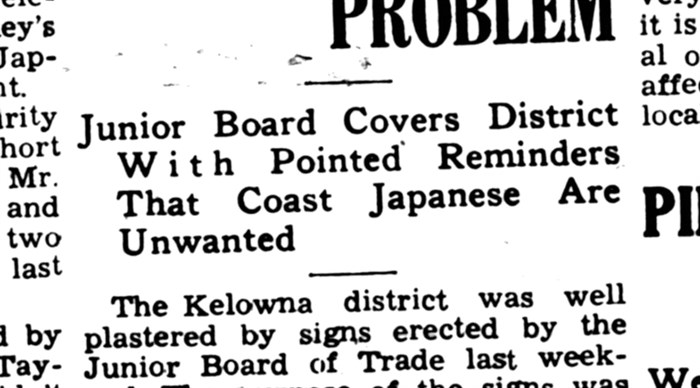

An archived article in the Kelowna Daily Courier from March 5, 1942, describes how the Junior Board of Trade put up these signs telling coastal Japanese people to stay out of Kelowna.

An archived photo of a Kelowna Daily Courier article about the racist signs.

Image Credit: Jeff Chiba Stearns

READ MORE: Chinese Canadian commandos who trained in Okanagan remembered 80 years later

The Okanagan had an established Japanese community during the war, so there was tension, and a distinction between Japanese-Canadians who lived in the Okanagan and folks who came to the region from the coast.

“The idea was it's like there's already Japanese here in Kelowna let's keep the rest out,” he said. “What it really boiled down to is a division of two groups, you had those that were already established in Kelowna and those that were basically being uprooted and had everything taken from them.”

There were 21,460 Japanese-Canadians who were interned during the war. Not only were they interned, the government seized their property to pay for their own imprisonment.

The Junior Board of Trade also posted other racist signs, according to a paper by Patricia E. Roy from 1990 called, “A Tale of Two Cities: The Reception of Japanese Evacuees in Kelowna and Kaslo B.C.”

“The Kelowna Junior Board of Trade was planning a mass indignation meeting and plastering the area with such signs as "Coast Japs, You Are Not Wanted. Keep Out," "Save Gas. Our Japanese Guests Must Have It," and "Hong Kong —Pearl Harbor—Okanagan?"” Roy wrote in her paper.

Roy wrote about how the Kelowna City Council, and some of the agricultural sector at the time supported the anti-Japanese racism in the community.

“The Kelowna City Council unanimously reaffirmed that no Japanese should be allowed to take up residence within the city,” she wrote. “Growers in Kelowna and southern areas did not want Japanese workers, but northern growers wanted long-term arrangements for this very satisfactory labour force.”

The distinction between Japanese folks from the coast and those living in the valley was about more than assimilation with the community, it was a legal distinction.

In 1941 there were 25 residents in Kelowna with Japanese origins, and roughly 500 in the surrounding area.

Racism against the Japanese locals was common before the war, but there was goodwill between Japanese Canadians and those who knew them.

Roy said in 1938, Captain C. R. Bull, the Liberal MLA for South Okanagan defended his Japanese constituents against politicians who wanted to ban immigration from Japan.

"The Japanese in my part of the country [who] show splendid co-operation and . . . stick to the rules and regulations," Bull said.

In 1942, following the attacks on Pearl Harbour and Hong Kong in December of 1941, the government told Japanese Canadians they were not allowed within 100 miles of the coast.

An artistic map of the 100 mile Japanese exclusion zone in 1942 from the documentary "One Big Hapa Family".

Image Credit: Jeff Chiba Stearns

Roy said Japanese Canadians in the Okanagan made an effort to make it clear that they themselves posed no threat to national security, which the Canadian government eventually admitted after the internment.

“Within days of the attack on Pearl Harbor, a delegation of Japanese headed by Rev. Y. Yoshioka presented Kelowna city council with a resolution signed by the heads of 130 families affirming their loyalty to Canada,” Roy said.

Pearl Harbour and the Battle of Hong Kong made Europeans in the Okanagan think that this 100 mile declaration would bring a flood of Japanese people to the valley. Any goodwill between the Japanese locals and the white residents was gone.

“The Courier, which had been counselling against vigilante action, now described every one of the "brown boches" as "a menace to our security," Roy wrote.

Bob Hayes, the director of the Okanagan Historical Society, said these signs were racism at its worst.

“These signs were directed at these Japanese Canadians who were being sent here from the coast. And of course the irony is they had no choice. They were ordered off the coast and ordered to move here or further inland. Some of them went as far as Saskatchewan. This is an example of racism at its worst. Blaming a group of people for something they had no control over,” Hayes said.

The late Roy Inouye spoke to Chiba Stearns for his documentary in 2010. He said the hatred and fear of coastal Japanese created tensions for local Japanese in the Okanagan.

“Some people lived in Kelowna already, a lot of them in the Rutland area but there was a sign on each end that said, ‘coastal japs keep out.’ The local Japanese people were identifying themselves as local Japanese and the others as coastal japs. There was a little animosity between the two groups in the Okanagan,” Inouye said in “One Big Hapa Family”.

Hayes said the local Japanese population was well integrated with folks of European descent prior to the Second World War and the oppression that followed.

“The local Japanese Canadian population was well treated as well as they should have been. My mom went to school with a number of them back in the 1920s and 30s. And (the sign) wasn't, I don't think, a reflection of how many people felt about the local Japanese Canadian population,” he said.

Signs with similar messages as the one in Kelowna were posted around the Okanagan. A photographed sign in Summerland reads; "Japanese and Germans keep out of Summerland."

The sign posted in Summerland during the Second World War.

Image Credit: Summerland Museum

The Summerland Museum’s archivist, Megan Gray, said there isn’t much information about the sign other than the fact that it was put up after Pearl Harbour and the Battle of Hong Kong, around the same time as the signs in Kelowna.

The sign in Summerland was reportedly taken down by Clare Elsey shortly after it was put up. Elsey ran a lumberyard, but Gray didn’t have any details about why Elsey decided to take the sign down. The fact that someone would take the sign down shortly after it was put up shows not everyone agreed with what those in power were doing.

The Fujinkai Ladies Auxiliary, also referred to as the Japanese Women’s group, is an example of how Japanese Canadian residents in Summerland were supportive of the war effort. The group knitted, sewed, and did whatever else they could to help with the war effort despite how the government treated Japanese Canadians.

The Summerland Museum has a new exhibit telling the story of Japanese Canadians in B.C. who lived through the period of internment and dispossession. Gray conducted research for the exhibit which opened on Nov. 22.

“I was unaware of the extent of the experience. I've learned a lot by talking to the communities about just the lasting legacy that I'll never understand. The emotional toll and the lasting impact its had on their generations. I think that's what's most important, is acknowledgement and recognition. And that's what I'm trying to do with highlighting it in the exhibit,” Gray said.

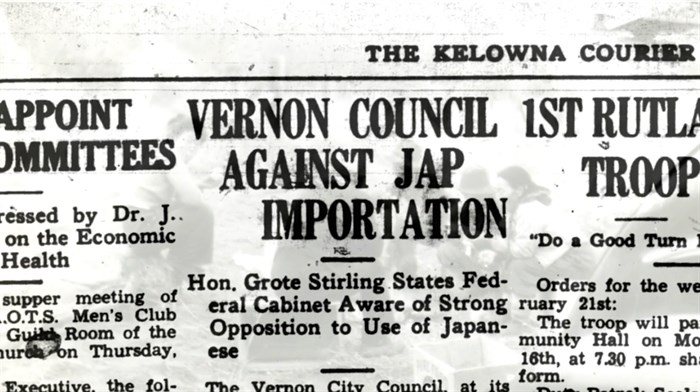

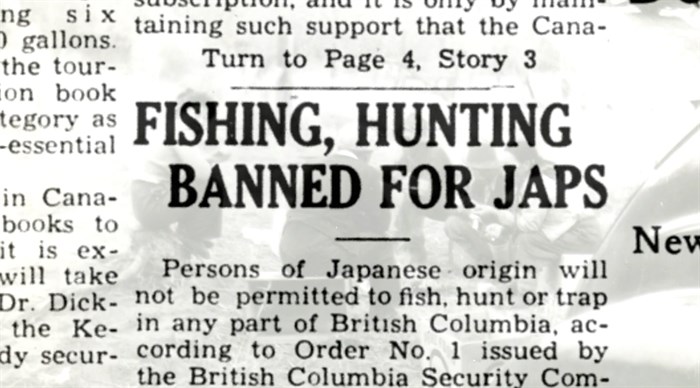

Stearns’ documentary included several images of headlines from the era about discrimination, internment, and dispossession of Japanese people during the war.

The Landscapes of Injustice was a seven year project that detailed the steps taken by the Canadian government to seize and sell the property of Canadians and then intern them during the Second World War.

Stearns’ documentary has an upcoming screening in Vernon at the Vernon Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre on Nov. 24.

Click here to watch “One Big Hapa Family” online.

A photo of an archived article from the Kelowna Daily Courier.

Image Credit: Jeff Chiba Stearns

A photo of an archived news article.

Image Credit: Jeff Chiba Stearns

To contact a reporter for this story, email Jesse Tomas or call 250-488-3065 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw. Find our Journalism Ethics policy here.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above. SUBSCRIBE to our awesome newsletter here.

News from © iNFOnews, 2024