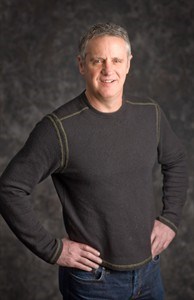

John Demont is the author of "A Good Day's Work: In Pursuit of a Disappearing Canada." THE CANADIAN PRESS/ho-Sandor Fizli

October 06, 2013 - 4:00 AM

TORONTO - When John DeMont was completing his book about vanishing traditional jobs in this country — think lighthouse keeper or milkman — he found "A Good Day's Work" had become much more than just a discourse on how some Canadians bring home the bacon.

"It sort of morphed into this book about Canada, using the disappearing work as a jumping-off point to talk about different aspects of Canada and the different things that are going," says the Halifax-based journalist and author.

"Not just work," he says, but "the iconic Canada — close-knit communities and small towns and everybody knowing everybody and being interested in a positive way."

"A Good Day's Work: In Pursuit of a Disappearing Canada" (Doubleday Canada) seems a natural followup to his previous book, 2009's "Coal Black Heart: The Story of Coal and the Lives it Ruled," a history of coal mining in Nova Scotia and the toll that disasters in the deeps took on colliers and their families.

Ancestors on both sides of his family were part of that history — one grandfather went down into the pit at age 11 to mine the black gold — but DeMont's father eschewed what had been the family business to work above-ground as a stockbroker.

And as the author writes in the prologue of "A Good Day's Work," growing up as a child in Halifax was an idyllic time for him — and for the country as a whole.

His reference year — 1967, when he was 11 — sees Canada celebrating its 100th birthday, with millions drawn from around the world to Expo 67 in Montreal, the Canadian economy at its post-war peak and the Toronto Maple Leafs winning their last Stanley Cup.

It was also a time when the milkman still delivered cows' bounty to many homeowners' doors, beef came from family-owned and family-worked farms, and parents and kids — and hormone-fuelled teens — piled into the station wagon on a summer's night to take in a drive-in movie.

It is that world that DeMont evokes in "A Good Day's Work," or rather what is left of it, as he tracks down Canadians still engaged in time-honoured work, the kind of jobs that built this country but are perhaps soon to be but a memory.

While natural resources jobs — forestry and fishing, for example — might have seemed an obvious fit, DeMont chose to go beyond "guys in the woods" and look into a broad range of skills among people in different parts of the country.

"I wanted jobs that in themselves were interesting, interesting enough that you could write about them, build a chapter around them," the 57-year-old explains during a recent visit to Toronto, one stop on a cross-country, multi-city book tour.

A cowgirl — well, a woman rancher really — takes him to Alberta, where long-held family acreages supporting herds of beef cattle are fast giving way to vast tracts owned by anonymous agribusiness conglomerates.

Marj Veno along with second husband Murray McArthur own more than 5,000 hectares of prime prairie grassland, raising 600 head of Angus cattle for breeding and beef.

And although Veno's daughter and son-in-law have chosen to stay in the beef business on a nearby ranch, the 50-something cowgirl who saddles up her horse at first light for a day checking the herds and mending fences is among the relatively few survivors of what is more and more considered a dying breed.

"She's hoping she can pass it on," DeMont says of the ranch, located in an area that has seen 40 neighbouring families sell off their farms in the last 30-plus years.

"But it just gets harder and harder. Who wants to work those staggering hours? Ninety-nine per cent of kids today want to go play hockey or 'Grand Theft Auto' down in the basement."

"A Good Day's Work" also profiles other disappearing vocations, among them a blacksmith, a travelling salesman and engineers on Via Rail's flagship train "the Canadian," which takes awe-struck passengers from Toronto to the lakes and forests of northern Ontario, across the prairies and through the Rockies to Canada's Pacific terminus, Vancouver.

As such jobs fade into history, it will not be just such workers' skills that will be lost, but also the sense of connectivity and community that they represent, DeMont laments.

Take Bill Bennett, the second-generation milkman who still delivers a few litres of one per cent to DeMont's house twice a week and occasionally shows up at the door to chat.

For the author, Bennett speaks to continuity, the way business was once conducted, when all kinds of products were delivered to consumers' homes.

"Now for a lot of people, you can drive through, get your coffee, get your food, you can bank," he says. All manner of goods — even groceries — can be purchased online, doing away with verbal exchanges between customers and sales clerks.

Home milk delivery is already a service of the past for most Canadians, particularly those dwelling in large cities, and it's likely to go the way of the dodo in the not too distant future.

DeMont hopes his book is one means of making sure these jobs and those who perform them are not forgotten.

"I think it's good for people and hopefully future generations to know that these people walked the Earth," he says. "Because there will come a time when they don't."

News from © The Canadian Press, 2013