Image Credit: Donnie Reid

July 22, 2020 - 6:00 AM

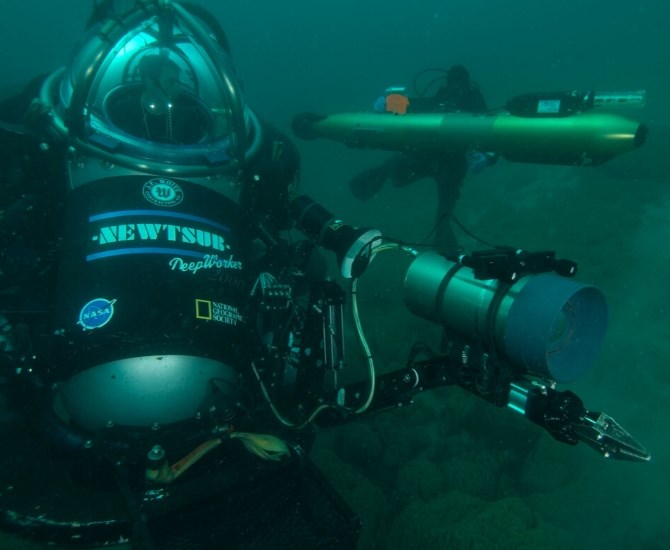

Early in his career, B.C. diver Donnie Reid had a reputation for going anywhere with his camera. When NASA called him with an offer, he said yes to the opportunity of a lifetime.

"I really was the luckiest diver in Canada for a long time," Reid said.

In the beginning, he was tasked with taking photos of the mysterious structures at the bottom of Pavilion Lake, located 40 kilometres northwest of Cache Creek.

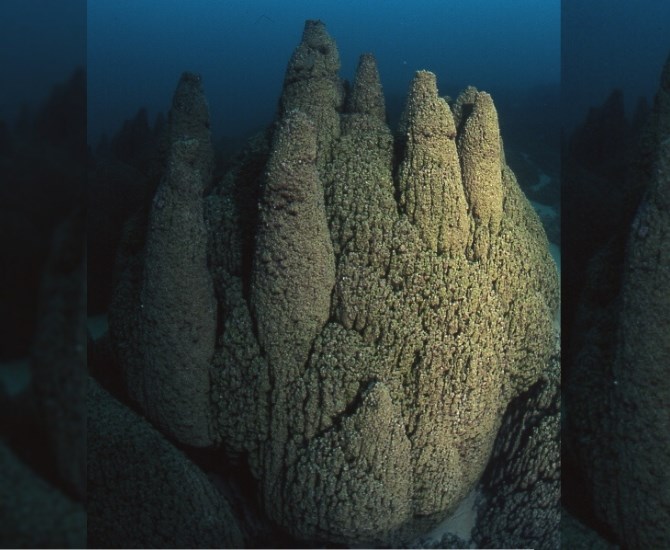

"People called them freshwater coral," Reid said. "But they’re not a coral."

They are bacterial structures called microbialites, which form by accumulating fossilized remains of micro-organisms and other materials over thousands of years.

READ MORE: iN VIDEO: The freshwater 'coral' this B.C. lake is famous for is not actually coral

The microbialites interested NASA because they represent some of the earliest life forms on Earth.

"They relate to the development of life on ancient Earth," Reid said. "They’re one of the first organisms that left a record in the rock history."

These organisms can provide valuable information to researchers exploring life beyond Earth.

"When they find life on other planets, this could very well be what they find," he said.

Reid began doing dives in Pavilion Lake with a small team of researchers in 1998. In 2004, NASA launched the Pavilion Lake Research Project in partnership with the Canadian Space Agency, and Reid was hired on as a diver full-time.

The microbialites were coral-like structures formed from the fossils of ancient organisms, located at the bottom of Pavilion and Kelly Lakes.

Image Credit: Donnie Reid

"I became a diving safety officer for the project for the first couple years," he said. "Then I became the project manager, then at the end I was a mission manager, so I oversaw operations."

Over the next 11 years, researchers from Canada and across the United States travelled to B.C. to study the microbialites in Pavilion Lake.

"It involved everything from diving to submarines to all sorts of things," he said. "People would come and go. I had some volunteers that helped me out, and they would take their holidays to come and work with us."

At its peak around 2008, the project involved 60 to 70 individuals. The team rented cabins at the lake during the summer.

In the morning, the team would meet over breakfast.

"Depending what science you were doing, they would get together and talk about what needed to be done," he said. "Then we’d break off and head out."

The NASA team conducting research on Pavilion Lake.

Image Credit: Donnie Reid

Reid estimates he has dived in Pavilion Lake 1,500 times.

"It’s not like a typical lake. Some lakes, you get down to the bottom, it’s not nice," he said. "They’re dark, they’re muddy. You shine your light somewhere and it just kind of gets sucked up into the blackness."

Pavilion Lake has a white calcium carbonate bottom, so even though divers were far from the surface, it was very bright down below.

"As far as I could tell, the structures were floating in the sand, they weren’t attached to anything," he said. "Really spectacular and beautiful. There’s a real awesomeness to it."

The team conducted surveys in Kelly Lake nearby, where the micriobialites were also present.

FILE PHOTO.

Image Credit: Donnie Reid

The structures in Kelly Lake ranged from one to 1.5 metres tall, the larger ones spanning three metres around. In Pavilion Lake, some structures surpassed that size significantly.

"There was what I called the Great Wall of China, because it was a wall, about one to 1.5 m high and about 75 m long," he said. "There was this one we called M.O.U.S, which stood for microbiolite of unusual size. Back in the days of (the movie) Princess Bride."

M.O.U.S measured about 39 feet around and 9 feet in height, he said.

Microbialite structures growing from the steep slopes of Pavilion Lake

Posted by Pavilion Lake Research Project on Sunday, March 15, 2009

Aside from conducting ground-breaking research, the team had little downtime.

"There were dishes to be done in the morning, there were dishes to be done at lunch," Reid said. "Things had to be looked after."

However, it wasn't all business all the time.

"We’d celebrate both Canada Day and July 4th, we’d have a big cake to celebrate both countries," he said.

"Pavilion was exciting. We did a lot of great stuff. But the thing that came out of it, was just the people were amazing."

Reid recalls once walking into a cabin to see his niece, who was volunteering as a driver, washing dishes with three other members of the team, one of whom was Mike Gerndhardt, an astronaut.

"They were laughing and joking, and just — that was Pavilion," Reid said.

"It didn’t matter what you did, you were an important and integral part of that team."

Evening meetings are filling up as the crew expands at PLRP!

Posted by Pavilion Lake Research Project on Friday, July 2, 2010

The community around Pavilion Lake also welcomed the NASA team with open arms.

"The Ts'kw'aylaxw First Nation, they supplied us with a couple students to work and people to help out with the program," Reid said. "One year they came in and did a dance and blessed our project, which was fabulous."

The locals were also very understanding and accommodating.

"The people at Pavilion opened up their arms for us, and allowed us to literally take over their lake," he said. "It was a big intrusion into their lives."

B.C. Parks also played an important role, assisting with the project and always willing to lend a hand, he said.

However, as all good things do, the project eventually had to come to an end.

Reid said that this was due to a number of different factors, including limitations on funding and many scientists being pulled to other projects.

"It was a fairly long haul," he said. "We produced an awful lot of high quality personnel, people did their doctorates."

After over a decade of working together, the goodbyes were difficult for the team.

"We won an award for teamwork from NASA," he said. "People would come together and we’d get there, people would be hugging each other. The last one we were there, people were crying. Because it was over."

Reid still keeps in touch with many of his colleagues from the project, many of whom live in the US.

"They’re just amazing people," he said. "I can’t say that enough about them."

To contact a reporter for this story, email Brie Welton or call (250) 819-3723 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2020