Kamloops and other Okanagan cities facing the looming iceberg costs of development

It’s been a well-known fact in planning circles for decades that sprawl development is not good for cities.

But, it’s only recently that some cities, like Kelowna, are coming to terms with that reality and looking to make changes, most recently by killing a 680-unit subdivision on the southern edge of the city.

Kamloops, which sprawls more than Kelowna, has had the anti-sprawl mindset for decades. It’s just that there’s historical reasons, quite different from Kelowna’s, for its far-flung neighbourhoods.

“We’re spread out up the two rivers so there’s a huge geographical distance from downtown,” Rod Martin, the city’s planning and development manager, told iNFOnews.ca. “We haven’t been encouraging higher density in these outlying neighbourhoods for quite a long time now. The suburban residential zone has been in place for decades.”

READ MORE: Kelowna has learned the 'iceberg' lesson of sprawling development

The Kamloops situation was created by the amalgamation of North and South Kamloops in 1969 followed by bringing outlying areas as far north as Heffley Creek and as far east as Dallas into the city around 1972.

That means Kamloops has been living with the cost of sprawl ever since and has developed policies to encourage growth in core areas that have services in place while allowing infill within and between existing far-flung neighbourhoods.

“There’s quite a lot of pressure to create more single-family lots because there’s quite a lot of demand for them,” Martin said. “But we’re not doing sprawl to the periphery.”

Sewer lines have been extended to Dallas and there is talk of extending them north to Rayleigh.

“When those utilities are there, we might as well intensify land use to the point where you make better utilization of those services.” Martin said. “But, when you want to leapfrog past, you get to the point where you’ve got to upsize the system or do large extensions or new reservoirs and upsize sewer lift stations and things like that. Then it doesn’t pay off.”

Kelowna grew in a different way, amalgamating with outlying communities like Rutland, Glenmore and Okanagan Mission in the 1970s.

Those were relatively close to the downtown core and were often well-developed communities.

It was after that amalgamation that city councils embraced sprawl developments to the far flung outskirts of East Kelowna (Gallagher’s Canyon), Highway 33 (Black and Kirschner mountains), Rutland (Tower Ranch), Glenmore (Wilden), McKinley Landing and the extreme South Mission (Kettle Valley and The Ponds), where services were stretched to the city’s extremities.

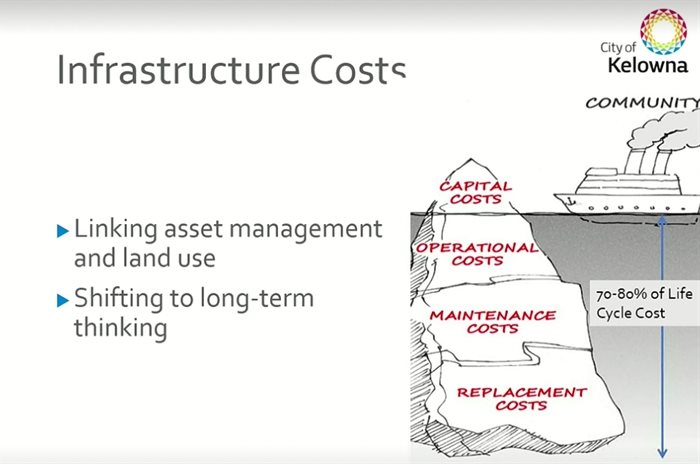

“For a long time in the development world, every new lot you brought on line brought a revenue stream for taxation,” Kelowna city planner Gary Moore. “Certainly, that’s true. Every new lot does bring on a revenue stream. But it also brings on a cost. In many cases the cost that comes at you is not a cost that accrues right away, it sneaks up on you 20-30-40-50 years later.”

That’s what he described an iceberg with a small upfront advantage but a huge cost down the road.

Both Kamloops and Kelowna face similar problems because they are both, geographically, two of the largest cities in B.C.

Kamloops is the fifth largest at 297.3 sq. km. and stretches 34 km from Dallas to Heffley Creek.

Kelowna comes in as the ninth largest at 211.8 sq. km. It’s about 23 km from Kettle Valley in the south to Kelowna Airport near the north end of the city.

Abbotsford ranks as the largest city in B.C. at 375.6 sq. km.

West Kelowna, which comes in at a mere 123.5 sq. km. is a young city, only being incorporated in 2007, so it benefits from the help of developers extending roads and sewers.

Its two largest single-family projects currently on the books are very close to the town centre. As the crow flies, the 900-unit Goats Peak proposal is a mere kilometre from downtown Westbank. Smith Creek, with 700 proposed homes, is about 2 to 2.5 km away but is right next to the city’s water treatment plant.

So, those don’t create huge iceberg concerns to planning manager Brent Magnan.

“Raymer is a different story,” Magnan said, referring to an area in the north-east corner of the city – north of Rose Valley Dam and West Kelowna Estates – where a number of property owners have been talking of doing a Comprehensive Development Plan in anticipation of developing that area.

“We’ve typically had concerns about the distance to the town centre and the amount of infrastructure that needs to be expanded to that area,” Magnan said. “The road is substandard and there’s no water and there’s no sewer so that makes a big difference.”

It’s not that West Kelowna doesn’t have concerns about single-family development, but planners are following an Official Community Plan that was put in place years ago and identified places like Goats Peak and Smith Creek as areas suitable for development.

But, a new plan is being drafted later this year that may, like Kelowna and Kamloops, focus more strongly on growth in core areas.

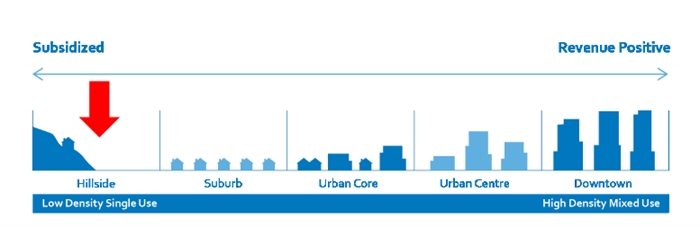

After all, it’s not just the sprawl that costs. It’s the density where tax dollars per acre are much greater in downtown cores where buildings sprawl up into the sky rather that out across the land.

In Kamloops, two high rise residential towers in the range of 20 storeys are planned downtown for the area of Battle and Nicola streets and a six-storey office building (The Hive) is under construction at Lansdowne Street – the city’s first new office space in years.

READ MORE: Work from home? New office towers in Kamloops, Kelowna defy the pandemic trend

“Every city in the Interior is dealing with the same thing: Penticton, Vernon, Kelowna, Kamloops, even other cities like Prince George and Nanaimo,” Martin said. “Everyone’s in the same boat. They’re trying to avoid more and more sprawl.”

Vernon, at 96 sq. km and Penticton at a mere 42, have less territory to cover.

There’s the added benefit that, relatively speaking, the Thompson and Okanagan regions are young when it comes to urban development.

“Kelowna is doing reasonably well in terms of that because our infrastructure is relatively new,” Moore said. “If you head further east, the older the community, the harder it gets. You go to places like Montreal and Quebec and Ontario, where infrastructure is aging and really running its lifecycle, funding its replacement is a real challenge. We’ve been more and more realizing that link is related to land use.

“As that idea has gained more and more traction and asset management has started to recognize the link, we’ve started to wrap our heads around the: ‘Holy smokes our infrastructure systems are really going to suffer and we don’t have a lot of money to fund them and why is that happening?’ The light bulbs have been going off in planning and in asset management.”

While Kelowna did put the brakes on the Thomson Flats proposal for the South Mission and break the pattern of sprawl development, there are still some 6,000 more mostly single-family homes planned for far flung subdivisions in Kelowna.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.