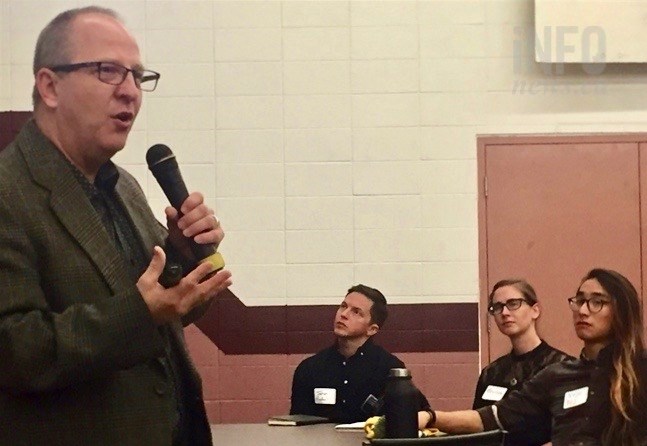

Wally Czech outlined the root causes of homelessness at a Journey Home Housing First forum in Kelowna on Tuesday, Oct. 16, 2018.

(ROB MUNRO / iNFOnews.ca)

October 16, 2018 - 4:47 PM

KELOWNA - Don’t blame homelessness on the people living on the streets, an expert on the issue told a group of concerned Kelowna residents and agency workers today.

“People on the streets are not there because of choices they made,” said Wally Czech at a Housing First workshop today. “They are there because of things that happened in their environment.”

Czech is director of training with the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness and is based in Lethbridge.

He addressed a workshop today, Oct. 16, that was promoting the Housing First strategy. He told iNFOnews.ca that Kamloops and Penticton have been doing some good things with the concept as well.

In his presentation, Czech cited a major U.S. study on Adverse Childhood Experiences that found that the root cause of homelessness is the same everywhere and lies with childhood experiences. If parents are struggling to cope, their children witness that and experience trauma that carries on to influence their lives.

There can also be a genetic component where the consequences of traumatic experiences can be passed on through a person’s DNA. Even people who receive organ donations may suffer from post traumatic stress if the organs came from a traumatized person.

People who suffered from a lack of childhood care are 13 per cent more likely to become homeless, while those who suffered physical abuse are 16 per cent more likely.

Czech explained that 80 per cent of people who experience homelessness do so on a transitory basis.

“They get some support and go out of homelessness and often we don’t see them back in that homelessness serving system,” he said.

It’s the other 20 per cent for whom the existing systems don’t work that Housing First is most trying to help. These are people, for example, who can’t keep appointments, stand in lineups or trust the system – or don’t want to be forced to abstain totally from drugs or alcohol.

“Twelve-step programs (such as Alcoholics Anonymous) are only five per cent effective because abstinence is a very high bar,” Czech said. “They may struggle with total abstinence, so relapse. If they fall off the wagon, we make them start over at the bottom. They get stuck in this revolving door.”

The Housing First concept originated in New York City in the late 1980s and first came to Canada in Calgary in 2008.

Housing First was initiated in Kelowna in 2016 by the Canadian Mental Health Association. Since then, they’ve housed 35 people, 32 of whom still remained housed.

Many traditional approaches break services into silos where the same person may get different responses from different agencies.

In Alberta, Czech said, the same government ministry that provides money for Housing First also looks after social housing and income support in often contradictory ways. For example, people need to have a place to live in order to get income support but they can’t get a place to live if they don’t have any income.

And that goes counter to Housing First as it uses things like rent subsidies to get people into housing as a first step to turning their lives around.

One of the biggest hurdles the homeless face in getting housing is the stigma in the community.

“Many people in our society have this bootstrap concept of homelessness,” Czech said. “They believe people have to get off their rear ends, get help for addiction or mental health issues and get off the street.

“Mental illness, addictions, those kinds of things are not the cause of homelessness. I’m not saying those things are not factors and don’t have an impact. Definitely they do. But I am not going to be convinced, in any way, that those things are the causes of homelessness.”

Again, he said it comes down to traumatic circumstances beyond the control of victims.

“People who experienced those things did not experience them at any fault of their own,” Czech said. “They did not ask to be put in residential schools. People with FASD (Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder) did not ask for that.

“People on the streets are not there because of choices they made. They are there because of things that happened in their environment. Yet we expect them to respond and react like people who didn’t have those significant experiences.

“Instead of thinking what is wrong with them, we have to think about what happed to them.”

That’s a key component to the Housing First approach to homelessness.

But, there is a problem with the Housing First strategy, Czech said.

When it started, it was so successful that some communities shifted all their focus to Housing First and lost sight of the programs that help 80 per cent of those on the streets.

Instead of a Housing First strategy, there needs to be a Housing First “synergy,” where different agencies work closely together to try to eradicate homelessness, he said.

Any money put into the effort, pays big dividends.

Czech referred to a 2009 study by the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

It found the average cost of putting a homeless person in shelters was about $2,000 per month. That cost rose to more than $4,000 to put them in jail or almost $11,000 in hospital for a month. Yet a $700 per month rental housing subsidy can end the cycle of homelessness.

But it isn’t quick or easy.

Jen Kanters, the Canadian Mental Health Association’s manager of homeless services in Kelowna, told the story of Rob, who lived on the streets in Kelowna for a decade.

Once a successful business and family man, he turned into a meth addict after his daughter died and his wife left him.

Rob was well known to police and was facing banishment from the city when the mental health association got involved and found him housing.

That led to a series of evictions after he brought too many friends to live with him in his apartment. He didn’t want to lose his street credibility because he believed he would be back on the street again.

His support worker never gave up on him. Rob finally started turning his life around. He still gets high every once in awhile, Kanters said, but in moderation. He would rather spend money on groceries than meth. Now he’s a bit embarrassed about the drain he was on the system and asking what he can do to give back.

Recovery is a series of small steps, Czech said. It’s not just about recovering from substance abuse, but making small changes.

“All people, regardless of their circumstance, with proper supports can improve their lives,” he said.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.

News from © iNFOnews, 2018