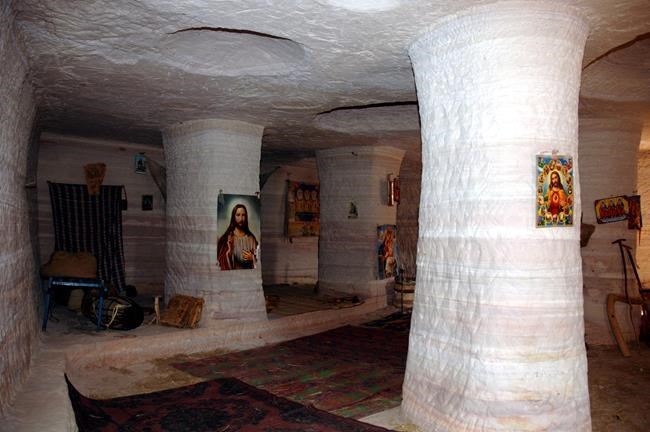

A church is shown in this undated handout image taken in Ethiopia. History Professor Prof. Michael Gervers has discovered that the lost art of carving churches out of rock is, in fact, still alive in remote regions of Ethiopia. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO-Michael Gervers

November 21, 2017 - 7:42 AM

TORONTO - Ten years ago Michael Gervers visited an ancient church cut into the side of a cliff in a remote region of Ethiopia. The history professor with the University of Toronto had been hunting down antiquities as part of his research on Christian artifacts when locals took him to the area.

Parishioners used ropes and a chain to haul themselves up to pray in the church carved into rock centuries ago. As Gervers looked around, he noticed another structure at the base of the cliff, also hewn from rock.

A craftsman and a small team had carved a new place of worship into the bottom of the cliff with a chisel and hammer a few years earlier to help the elderly who could no longer climb to the church at the top, Gervers says.

"It was surprising, I mean, who makes these things these days?" Gervers says in an interview.

Scholars believed the craft of cutting churches out of rock — practised predominantly in Ethiopia — had been largely lost to time some 500 years ago, Gervers says. But his research, which documents the practice that can transform rock face into free-standing buildings, proves otherwise.

Now he's trying to find out if the work was carried on continuously over the centuries, with the craft discreetly passed down from generation to generation, or if a renewal of the traditional practice has quietly been underway.

"The craft is alive, but just barely," he says.

In early November, Gervers released some of his findings to the world when he published interviews with craftsmen, priests and parishioners, as well as images of the Ethiopian rock-cut churches he's seen, on the university's website. The web resource is expected to eventually contain hundreds of photographs, transcripts and hours of video interviews about the practice.

At some point, hopefully in the next year, Gervers says his findings will be published in an academic journal. But he also wants to get the word out in an effort to preserve the craft.

In 2014, the Arcadia Fund, a philanthropic foundation known for preserving languages, approached Gervers to see if the craft of hewing churches from rock was still practised, and if so, to document it.

Gervers already had a lead from his trip to Ethiopia in 2007 and began his hunt in 2015. Over the past two years he and a few colleagues in Ethiopia and Europe have been scouring the country looking for evidence.

So far, they've found 20 modern-day churches carved from rock, Gervers says.

"There is very little information that these churches are still being built, only those who live near a church know, no one else in Ethiopia really knows," says Bayenew Melaku, an architect at the Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, Building Construction and City Development at Addis Ababa University, who is working with Gervers on the project.

"It is an endangered heritage because the knowledge is not well exposed and we're worried this tradition will go extinct."

It is believed that churches were built out of rock as early as the 12th century, and possibly earlier, Gervers says. They are of two styles: cave and monolithic churches.

Cave churches are essentially cut into the side of a cliff whereas monolithic churches are cut out from the rock, working from the surface digging down to create both the outside and inside of a free-standing structure.

Some of the most famous examples of monolithic churches carved from rock exist in Lalibela, a town in a mountainous region of northern Ethiopia where a complex of rock-cut churches have been designated a UNESCO world heritage site.

But the pilgrims and tourists who flock there should take the three-hour drive across the valley to a spot called Ambager, Gervers says. There they'll find a hermit working away with a chisel and hammer.

The man, named Gebremeskel Tessema Mola, has withdrawn from society and, inspired by God, has dedicated much of his life to creating a monolithic church complex that so far spans about 35 metres in width and up to seven metres in height, Gervers says.

"He's an artist because he has this great plan in his mind — he doesn't seem to have plans on paper — but knows exactly where he's going," Gervers says. "It's incredible how much he accomplishes every year."

Gervers interviewed Gebremeskel, who goes by his first name, and took a tour of the church the man has slowly been carving out of rock since 1995, discussing the craft at length.

"We had a sense of duty to prove that, by the help of the Holy Spirit, our forefathers really made what they made," Gebremeskel told Gervers, according to a translated transcript of an interview the professor shared.

"That is why we have been working on this."

Gervers' work has also drawn the attention of the grandson of Ethiopia's last ruling emperor.

"It exposes the richness of Ethiopia's culture and traditions, especially in its Christian form, to the world," Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile-Selassie, president of the Crown Council of Ethiopia, said in a statement.

Gervers headed back to Ethiopia on Tuesday to continue to his work.

News from © The Canadian Press, 2017