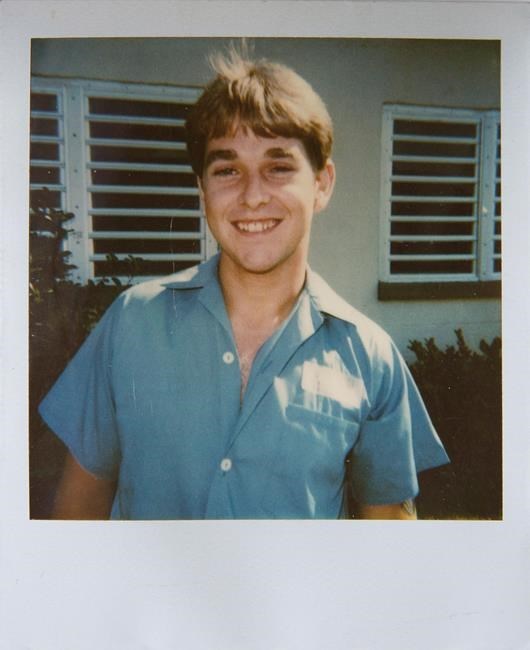

William (Russ) Davies poses for a photo in a Florida prison in this March 1988 handout photo. Davies is currently serving a life sentence in a Florida prison for a he denies committing in an incident 30 years ago. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO

June 22, 2016 - 9:07 AM

TORONTO - Almost three decades ago, a jury in Florida convicted a young Canadian misfit of gunning down an acquaintance after what was potentially a death-penalty trial that in essence lasted only seven hours.

As a helicopter waited to transport the Toronto-born teenager to death row, the judge instead accepted the jurors' sentencing recommendation: Life in prison.

The state's prison system swallowed William Russell (Russ) Davies and has, for 30 years, refused to spit him out. While his five co-accused walked free long ago, Davies's presumptive parole release date is still another 30 years away.

"I have been in the worst shitbag institutions that the state of Florida has," Davies, 48, said in a recent interview from prison. "I have lived in a hell that you probably have watched on television and don't really have a grasp of."

Davies was involved in a serious crime, so it's no surprise he found himself enmeshed in the steely maw of Florida's justice and penal system. Yet police and court records, trial transcripts and years of post-conviction documentation suggest Davies himself fell victim to an overworked system that appeared to place expediency above justice, and then threw up a wall of indifference.

"We've been voices crying in the wilderness about this," said Loftus Cuddy, a now-retired Toronto lawyer familiar with the case who believes that Davies's conviction on first-degree murder was nothing short of a travesty.

At minimum, Cuddy said, the evidence presented at trial reveals considerable reasonable doubt.

— MISFIT ON THE RUN —

Davies was just shy of 18 years old in the spring of 1986 when he pinched a credit card and cash from his mother's wallet and left home in Richmond Hill, Ont., for what would be the last time. He made it across the border in a car stolen from his boss at the Tim Hortons where he had been training as a baker, and high-tailed it down to Daytona Beach, Fla.

The trip south was the culmination of increasingly turbulent years of skipped school, defiance, strained relations with his parents and petty crime.

"I was just being a dummy. I didn't want to hear nothing. That's all. I was a kid that thought I knew everything and nobody could tell me nothing. That's the truth of it," Davies says now.

"Everything in my life I was touching was messing up, and the easiest answer I had was to start again."

A fresh start it hardly was. Within weeks, Davies had fallen in with "The Family," a rougher older group of mostly shiftless louts — some with criminal records — whose existence revolved around stealing alcohol and cigarettes, drinking themselves blind, roaring around Daytona Beach and taking whatever street drugs they could get their hands on. Some carried guns.

It was, Davies says, crazy and out of control but the rebellious teen loved it.

"I thought I was all of a sudden somebody important," he says. "I was hanging out with these big tough guys."

All, however, was not well in The Family. Especially after Jack Chaney drove away from a golf-course burglary, leaving the others to walk home.

— MURDER BY MOONLIGHT —

One day in June 1986 — the actual date is not clear — members of "The Family" did what they did best: They stocked up on beer and drove around Daytona Beach.

Behind the wheel of the Cadillac up front was George (Georgie) Hughes. On the front seat next to him were Carrie (Ma) Parker and Timothy (Big Tim) Hagen. Passing in and out — mostly out — on the back seat was a very drunk James (Jimbo) Noojin.

Following the Caddy was Chaney in his Mercury Cougar with John (John-John) Cavallaro next to him. An unhappy Davies was in the back. Chaney was drunk, driving over curbs and mouthing off at Davies. On at least one occasion when they pulled over, a fuming Davies tried in vain to get in with the others in the lead car but they wouldn't let him.

Some time late that evening, the two cars drove into a secluded wooded area in Tomoka State Park north of Daytona Beach. They broke through a chain barrier and pulled into a clearing, Davies riding on the hood of the Cougar. Some of the others got out of the cars.

What exactly transpired is now impossible to discern because of conflicting witness accounts. But here's how Davies, who had turned 18 just weeks earlier, says it went down:

Chaney was talking trash and Davies says he walked over and hit him on the side of the head with a gun, which went off, the bullet whizzing by Hagen into the woods. Chaney fell to the ground.

"I froze when the gun went off. I'm scared to death. I don't know what to do. I'm stuck," Davies alleges.

Hagen, angry at the gunplay, walked over to see what had happened to Chaney, who by some accounts was snoring, by others was in his death throes. Hagen twice slapped Chaney, who Davies says was trying to get up, and said, "He's all right." At that point, however, Davies alleges Cavallaro went over, grabbed the gun from him, kicked Chaney in the jaw, put the gun under his chin and shot him.

"I was just stunned," Davies says, "Everything was moving like slow motion."

— BEHIND BARS —

Chaney's decomposing remains were found about a month after his murder. In his pocket was identification and registration papers for his Cougar, and police would soon arrest all of those who were there the night he was killed.

Davies, however, had already been arrested within days of the killing for an unrelated offence.

For reasons that remain unclear — but possibly because he lied about his age — Davies was placed in a juvenile detention centre where, weeks later, police would arrest and charge him in Chaney's death. There is no evidence they attempted to reach his parents or notify Canadian consular officials about their ostensibly underage inmate. Davies refused to talk to investigators, insisting he see a lawyer.

Initially, all six were charged with first-degree murder. Raymond Cass, a legal-aid lawyer, was appointed to defend them all.

At one point, Davies says he was escorted to an interview room where he was confronted by the investigating officer, prosecutor and two correctional officers. Cass, who was supposed to have been there, was absent. What really drew his attention, Davies says, was a detailed drawing of an electric chair on the back wall — darkly known as Ol' Sparky. On either side were the monikers of his co-accused. On the seat, in bold letters, was written "Russ," Davies says.

The following day, in the same interview room and with the same drawing still on the wall, Cass told Davies he was withdrawing from the case on the grounds of "irreconcilable conflict." All of Davies's co-accused, some of whom were housed together in the adult section of the prison, were brokering plea deals. The shifting finger of blame was coming to point squarely at the Canadian teen.

In mid-October, Carmen Corrente, a lawyer who has since gone on to become an assistant attorney general, was appointed to defend Davies.

"Carmen Corrente probably did more to put me in prison than anyone else did," Davies alleges.

The new lawyer seemed to view the case as an "inconvenience," Davies says, spending just a few minutes at a time talking to him. While Corrente pushed his client to plead out and secure the best possible deal, Davies refused, insisting he hadn't killed Chaney.

"I wouldn't have pleaded out for nothing," Davies says. "I'd rather do the time that I've done than plead guilty to something I didn't do."

Despite repeated requests, Corrente refused to discuss the case with The Canadian Press.

By the time Davies got to trial in March 1988, his five co-accused had pleaded guilty to lesser crimes such as accessory after the fact for failing to report the murder. All were handed sentences ranging from probation to five years.

Cavallaro, who most everyone agrees fired the second shot, pleaded guilty to attempted murder and was given 12 years. He was released in 1990 after serving just two years. The Canadian Press tried to contact him in prison — he is currently incarcerated for an unrelated offence — but received no response.

In the end, Davies alone stood trial for Chaney's killing.

"I realized I was in deep shit when they put me in a juvenile block, and everybody I talked to and told that I was 18 years old told me to shut up. I realized I was in deep shit every time I called my parents and told them I needed help they told me, 'That's your problem, you got yourself into the mess, get out of the mess,'" Davies says.

"I realized I was in deep shit when I was absolutely by myself and there was no one in the entire world that was going to do or say anything on my behalf."

— STATE OF FLORIDA vs. WILLIAM RUSSELL DAVIES —

Transcripts of the trial's opening statements have long been shredded, Florida prosecutors say, so what exactly was said cannot be verified. However, Davies says Corrente promised jurors he would testify. In addition, the lawyer himself later acknowledged that he told the jury he would call co-accused Tim Hagen, whose testimony might have altered the course of the trial. But Corrente called neither man to the stand.

Over the next day and half, prosecutor Gene White called seven witnesses, including the investigating officer, who had taken statements from all the co-accused except Cavallaro, the man Davies says actually killed Chaney. Also testifying was the man who found the body, a medical examiner, and a prison guard, who told jurors Davies had confessed to the murder — a version disputed by Davies and by other cell-block inmates, according to their affidavits. The defence interviewed none of them.

Evidence at trial included the fact that Chaney had been shot in the head, and police had found a single .38 calibre bullet near his skull.

But the prosecution's star witness was Jimbo Noojin, who had been passing in and out of consciousness on the back seat of the Caddy after drinking at least eight or nine beers.

"When I was climbing out the window, I had to go to the restroom; I seen Russell Davies shoot the guy in the head," Noojin told White. "I was already going to the bathroom at that time."

Noojin went on to describe he was about seven metres away, and Chaney was shaking on the ground when Cavallaro took the gun and shot him again.

"How was the lighting? Was there any light?" White asked.

"It was light out. It was dark, but there was a bright light outside."

"Moonlight?"

"Yes."

In cross-examination, Corrente noted he had previously asked Noojin what Chaney did after being shot.

"And your answer was: 'All I seen was part of it. They knew John-John (Cavallaro) did it.' How much of what happened did you see?"

"I seen Jack Chaney get shot by Russell Davies and then John-John took the gun and shot him again."

Noojin had difficulty remembering details or clarifying several discrepancies between his testimony and what he had said in earlier statements. But he was steadfast: "Russell Davies pointed right to his head and then John-John got the gun and shot him, too, somewhere in the body part."

"Did the body stop moving then?"

"Yes it did."

"Did you ever hear Hagen say he was going to kill that sucker, meaning Chaney?"

"Yes, sir. I heard him say that."

After the guard testified to Davies's purported spontaneous confession, Corrente pushed the judge to stop the trial and acquit his client, partly because Noojin's eyewitness account was clearly suspect, and partly because, he said, the state had failed to prove premeditation.

"I'm going to deny the motion," Judge Kim Hammond responded. "I will leave it with the jury."

The defence called just one witness: Associate professor Robert Dailey, an anthropologist who examined Chaney's skeletal remains. He testified the bullet had entered under the victim's chin and exited through the top of his head — consistent with Davies's assertion that Cavallaro had shot him as he lay on the ground.

He also said Chaney's jaw had been broken by "blunt force trauma" — consistent with Davies's version that Cavallaro had kicked him in the head before shooting him.

But White threw that evidence into doubt by highlighting the fact that Dailey, based purely on examination of the bones, had been way off in his estimation of the victim's age.

In closing arguments, White stressed the bad blood between Davies and Chaney. He highlighted Noojin's eyewitness testimony, the guard's recounting of the confession, and a note Davies allegedly wrote in prison in which he said he was thinking of pleading guilty. Not only was there no reasonable doubt that Davies had planned to kill Chaney and then did so in cold blood, White said, there was "not an iota of doubt."

Corrente, for his part, admitted to jurors he had made several mistakes — including promising to call witnesses and then not calling them.

"I apologize for misleading you," he told the jury, before an occasionally contradictory closing statement in which he argued the state had failed to prove Davies had planned the killing or fired the fatal shot. At most, Corrente said, his client was guilty of aggravated battery.

In a rebuttal closing, White dripped with scorn as he addressed the jury.

"If this isn't the best case Volusia County has seen for a long time," White said, "I will eat my notebook here."

— SEVEN HOURS TO LIFE —

Less than two hours later, jurors returned their unanimous verdict: Guilty of first-degree murder. Davies sat stone-faced. His mother, Carol Davies, collapsed in hysterics, sobbing "my baby, my baby," and had to be escorted from the courtroom.

Corrente asked for extra time to prepare for the life-or-death sentencing phase of the trial.

"I don't really have a lot of time," the judge admonished. "I have probably 30 sentencings to do tomorrow that I am going to be doubling in with these matters."

Among the witnesses Corrente put on the stand for pre-sentencing was Hagen, the man who was supposed to testify at the trial but never did. Hagen told the court he heard a shot, turned around and saw Davies holding a gun.

"(Chaney) was still breathing. I said we ought to get him an ambulance. John Cavallaro stepped over him, said 'F--k that,' grabbed the gun from Russ and shot him again. I didn't see where he shot him."

"Did it look like a shot to the head?" Corrente asked.

"Yes it did. He was pointing it at his head when I turned around."

Ultimately, the jury came back with a recommendation of life with no parole for at least 25 years. Judge Hammond agreed.

"You have been a burden to humankind," Hammond said. "You will live in your own kind of hell on Earth, that is unless you find another way."

Before dismissing everyone, Hammond noted how Davies's mom had screamed when her son was convicted, then expressed disdain that Davies himself had not shed tears or shown any emotion.

Almost 30 years later, Davies explains his lack of reaction, saying he was so distressed, he had broken out in hives.

"He didn't see the rashes that were all over me," Davies says of the judge. "I was just absolutely stunned. I was scared to death. I was in actual physical pain."

— NO LIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL —

Corrente filed an appeal a month after the trial ended. The Appeal Court rejected it without saying why. Instead, Davies began pushing to serve his sentence in Canada.

In 2003, documents show, Canada agreed to take him back. However, Florida, without giving reasons, refused then and on other occasions to let him go. Officials, including the state governor and the woman in charge of the transfer program, ignored requests for comment.

What is clear is that Florida adheres to a "life means life" world view, while Canada hews more to the philosophy that criminals should indeed be punished — but also get the opportunity to turn their lives around and return to the community.

Except in the case of the most hardened, incorrigible killers guilty of the worst murders, most people convicted in Canada seldom see even two decades behind bars. Had the exact same crime been committed in Canada, legal experts say, the odds are slim Davies would have been convicted of first-degree murder in the first place, or still been behind bars 30 years later even if he had been.

A current application — made almost two years ago — to transfer to Canada to be closer to his ailing parents is still somewhere in the bureaucratic maze, although Correctional Services Canada has done legwork on what supports Davies might have if he does return.

Florida denied prisoner #111211 parole last year. He can ask again in 2019 — considered a small victory — but his current presumptive parole date of 2046 remains decades away. However, following depositions to the parole commissioners last year by Ellen Gardner and Mary-Beth Denomy, two Toronto women who have offered support since learning about his case years ago, Davies was transferred to a better facility, where he now remains.

"First I survived by being an idiot, just living in a void of caring for nothing," he says of his earlier years. "When you don't care about nothing, you don't care about yourself."

Those days are now behind him, he says. He has, he insists, become a much better person, a change his parents and supporters say is real.

"What really took place is that I got embarrassed. And that's the most truth that I can give you," he says.

"I was just ashamed to the core of my existence that I had kissed an entire life away and created an entire life of victims and people that I hurt and I said, 'I refuse to let that continue.'"

News from © The Canadian Press, 2016