Is crime a legitimate concern for Kelowna supportive housing?

It has been four years since the first of five supportive housing complexes opened in Kelowna.

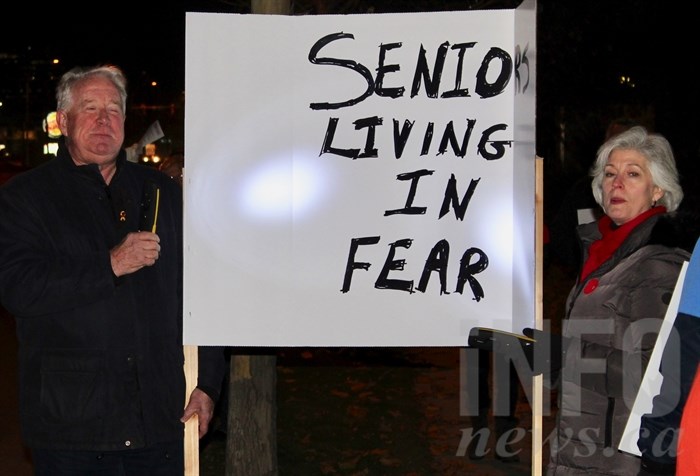

Some of those projects triggered widespread and vocal opposition from residents who feared an increase in crime.

Back in the fall of 2018, Hearthstone opened in a commercial area off Highway 97 near Leathead Road.

Since then, four other facilities opened. The newest, on McCurdy Road, opened almost two years ago.

At the request of iNFOnews.ca, city staff dug into the calls for service stats in the neighbourhoods surrounding those homes – meaning calls to police and bylaws before and after the openings.

"In some cases we see an increase in calls for service in relation to property crimes in and around supportive housing sites in the first six to 12 months,” Darren Caul, the city’s community safety director said. “In other cases, we see no change in calls for service and, in some cases, we’ve actually seen a decline in calls for service around a site. The results really vary, and they change, and there are outside factors that can really contribute.”

Caul spoke about the calls for service in general terms but did not provide detailed numbers for each site.

“What I can’t do is provide very specific numbers because, first of all, the numbers are imperfect in themselves and, secondly, I think people can get really caught up on the raw numbers,” he said.

When pressed for the numbers, he contacted the RCMP to get clearance from them to use their data.

“I’m advised that RCMP policy precludes them from releasing data relating to specific addresses/sites,” he wrote in a follow-up email.

The RCMP have yet to provide iNFOnews.ca with a copy or details about that policy.

What does seem consistent between sites is that, whenever one of them opens, there is an increased sensitivity from neighbours as to what’s going on in and around those facilities, some of which have supervised injection rooms for drug users.

The calls for service around both Hearthstone and Heath House (which opened on Highway 97 near Hearthstone in January 2019) doubled in the first few months after they opened.

READ MORE: Kelowna supportive housing building, Heath House, makes moves to improve neighbourhood safety

“We saw, in both cases, a receding of those calls for service over time and, in fact, we see that those sites are now aligned with, or even below, city trends,” Caul said.

Heath House was opened in a former motel bordering on a neighbourhood that had an existing problem with crime. That continued after the facility opened but some neighbours were prone to blame incidents on the housing project.

On the opposite end of the scale were Samuel Place that opened on McIntosh Road in Rutland in March 2020 and Stephen Village, which opened on Agassiz Road behind Orchard Plaza five months later.

“In those cases, we actually saw a decline in calls for service in the months and year after they opened, so it was completely the opposite story to that of Heath House and Hearthstone,” Caul said.

There was little public reaction to the McIntosh Road project but Agassiz Road triggered large and vocal protests when it was proposed.

“We expect a large number of younger males with heroin addiction to be housed in that building,” neighbourhood spokesman Richard Taylor said at the time. “This is a neighbourhood where the biggest demographic is elderly widows who want to walk around the neighbourhood. I liken it to whether you would want to move a meth addict in with your grandmother.”

READ MORE: Protesters greet visitors at open house on Kelowna’s latest supportive housing project

Yet, the calls for service went down after it opened.

There were a couple of reasons for that, Caul said.

“Those two places opened right at the time that the COVID pandemic hit,” Caul said. “We saw a very significant and immediate drop, overall, in property crime in the first year of the pandemic.”

Another reason is, given the problems triggered by the earlier openings, the city created a “community inclusion model” where neighbours were invited to information sessions prior to new facilities opening. They could later sit on committees, along with operators, to deal with issues as they come up.

“We now have a mechanism to actively seek out those voices and we are in a much better position today to respond when we see real issues emerging,” Caul said.

If the problem is directly related to the tenants in the building the city can, for example, work with the operator to make changes in how they deal with particular individuals.

Or they can increase security measures in the area or look at environmental issues that can be improved, such as installing lights in darker parts of the neighbourhood.

That doesn’t mean it’s all peaches and cream.

“There are individuals in communities in and around emergency shelters and supportive housing sites who have, absolutely, been impacted,” Caul said. “My team and I absolutely hear those concerns, especially since we’ve entered the community inclusion model.”

The newest project, McCurdy House, may offer a better measure of how these changes are working and what to look to in the future if, and when, more supportive housing is built.

When it was announced in June 2019 that the Knights of Columbus had sold their hall on McCurdy Road near Rutland Road to B.C. Housing for a supportive housing project, there was immediate pushback from the community.

READ MORE: Despite fierce opposition, Kelowna council strongly supports housing project for homeless

That led to the creation of a group called Rutland for Safe Neighbourhoods which collected signatures from almost 13,000 Kelowna resident protesting the fact that it would be a wet facility – meaning residents were allowed to consume drugs and alcohol in suites – and it was too close to schools.

In the end, the city and B.C. Housing agreed there would be no supervised injection site in the building and that it would only house people who agreed to work towards recovery and not use illegal drugs. It also had additional security for the first six months.

READ MORE: Controversial Kelowna supportive housing facility will be 'dry'

That may have had n major impact on the calls for service once it did open.

“The calls for service remained the same in the months and years that predated the opening and in the nearly two years since,” Caul said.

Overall, he paints a mostly positive picture of the impact supportive housing had on neighbourhoods.

“Often I hear heart-warming stories of individuals who were in vocal opposition and deeply concerned about the introduction of a supportive housing site in their community who are now involved in the local advisory committee and become, in fact, allies and supporters as they have come to understand the real issues and the realities of the issue,” he said.

How have these facilities impacted your lives? Let us know in the comments section below.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above.