How an Indigenous trail through Kicking Horse Canyon grew into a super highway

The TransCanada Highway through the Kicking Horse Canyon has some of the most difficult and dangerous highway-building terrain in Canada.

So why are the provincial and federal governments spending more than $600 million over two decades to upgrade an old trail to make it into a super highway?

Ironically, safety may be the reason there was a trail through the canyon in the first place but it was later chosen simply because it was the shortest route.

“Kicking Horse Pass was used primarily by the Ktunaxa (Kootenay) as a seasonal route to the plains on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains,” the Canadian Encyclopedia says.

“While other routes existed to the south of the (Yoho National) park, these southern passages put the Ktunaxa in contact with the Siksikaitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy), with whom they were not friendly. Instead, the Ktunaxa likely used Kicking Horse Pass to access the plains, where they hunted bison on the territory of their allies, the Cree and the Stoney-Nakoda, and traded ochre with them.”

In 1858, the Palliser Expedition explored the canyon. The group’s physician, Dr. James Hector, reportedly received a disabling kick from a horse there, thus giving the canyon its modern name.

READ MORE: iN VIDEO: Kicking Horse Canyon construction set to wrap up week early

“The pass was virtually unused until after 1881 when the Canadian Pacific Railway decided to adopt it as their new route through the Rockies, foregoing the earlier preference for the more northerly Yellowhead Pass,” the Federal Heritage Commission reports. “This decision altered the location of the line across western Canada and dramatically affected the development of the West.”

According to Transcanada.com, that route was chosen simply because it was the shortest, even though it required grades up to 4.5% that forced extra engines to be hooked on to pull trains up “The Big Hill” and resulted in numerous accidents as braking was very difficult on the downward trip.

That problem was solved with the building of two spiral tunnels in 1907 with the old rail bed eventually becoming part of the TransCanada Highway.

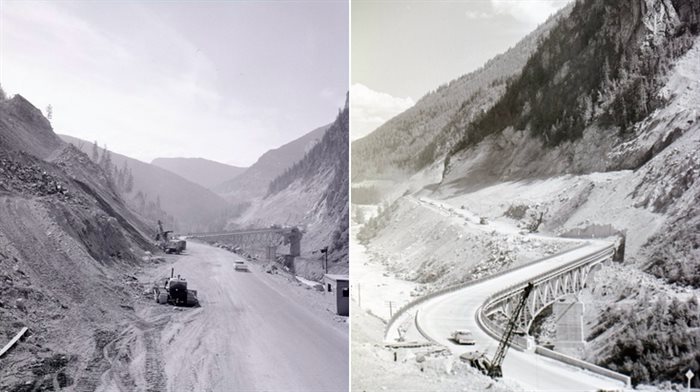

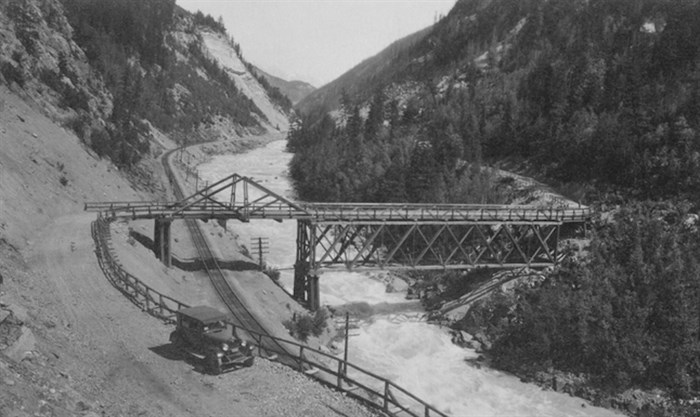

The first major bridge crossing the Kicking Horse River seems to have been the one pictured above, from the 1930s. It wasn’t until the 1950-60s that the Trans-Canada Highway was pushed through and that bridge was replaced.

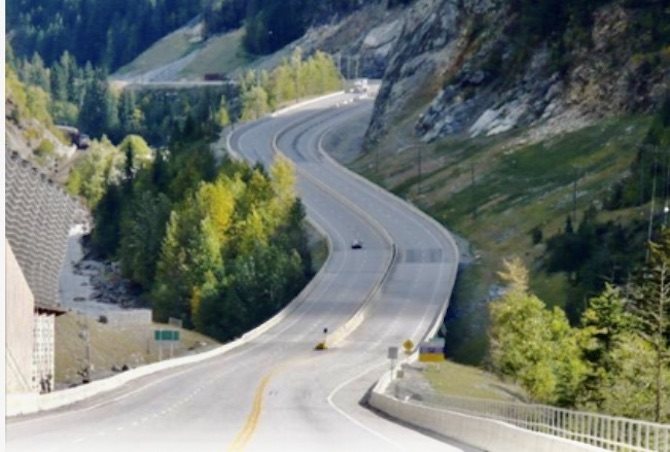

That served the travelling public well enough until the latest rebuild started in 2003.

Along with 3.2 km of highway upgrades and the new Yoho bridge came a “Great Wall” at a total cost of $64 million.

“The canyon is steep and narrow and has the Kicking Horse River and the Canadian Pacific railway line running along its course,” says an article in the Canadian Consulting Engineer publication. “Making the site even more of a challenge is the instability of the terrain, with its avalanche and rockfall chutes.”

That article goes into technical details about the site chosen for the bridge and things like using “steel delta frames on top of the pier columns” to support the bridge’s superstructure and “piled slab supports” to transfer the weight of the bridge directly to the bedrock below.

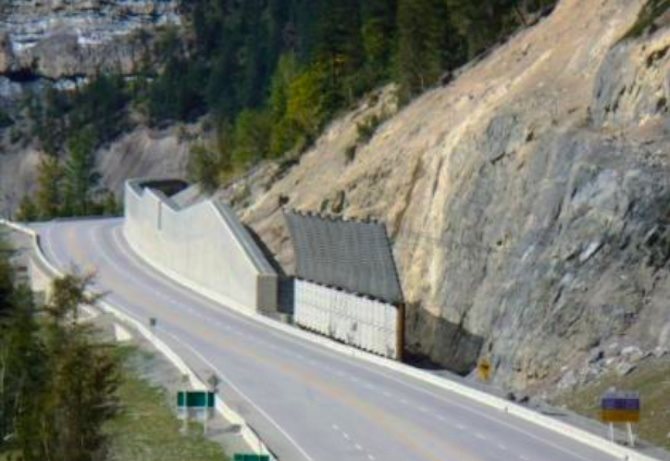

It was finished in 2006, is 270 metres long and crosses the river at a skew angle of 60 degrees. It includes what was dubbed “The Great Wall.”

“To combat a perpetual problem with rock falls along the west approach, a massive retaining/rock catch wall was designed,” the article says. “It is 485 metres long, reaches a maximum height of 11.6 metres above the highway, and can withstand the impact of rocks up to 5,000 kilograms travelling at velocities up to 35 m/s.”

The Yoho Bridge replacement was the first of four phases to upgrade the highway through the mountains at a cost of more than $600 million with the province paying about one-third to the federal government’s two thirds.

READ MORE: iN PHOTOS: These engineering wonders in Kicking Horse Pass are virtually invisible

“Three phases of work have transformed 21 kilometres of narrow, winding two-lane highway into a modern four-lane, 100 km/h standard,” the BC Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure website says. “Construction of the fourth and final phase to complete the remaining – and most difficult – 4.8 kilometres is expected to be substantially complete in winter 2023-24.”

That means traffic disruptions continue to be the norm for the highway.

Half-hour stoppages during the daytime and evenings along with overnight closures from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. will continue through to the end of November. Further interruptions can be expected beyond then.

Check the Highway Status Calendar or DriveBC for more information and updates.

More disruptions are happening to the west of Golden as the province four-lanes stretches along that section to Kamloops.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above. SUBSCRIBE to our awesome newsletter here.