Highway 3 was BC’s first trans-provincial highway despite reverting back to nature

Back in the earliest days of BC’s European history there were intense territorial battles between the U.S. and British governments trying to reap the benefits of dozens of gold mines in the province.

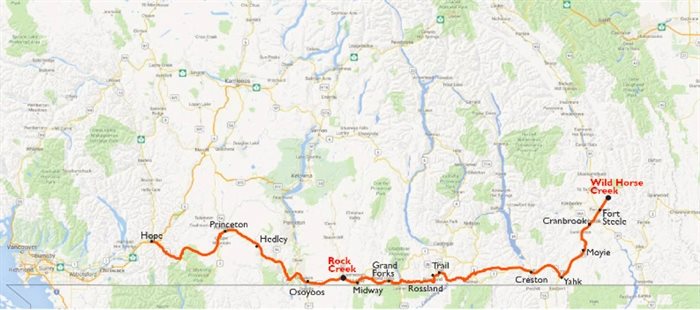

Gold rushes, first in Rock Creek and later in the East Kootenays, triggered two spurts of road building across the southern reaches of BC in order to keep the Americans at bay.

But when the gold ran out, both efforts were mostly abandoned.

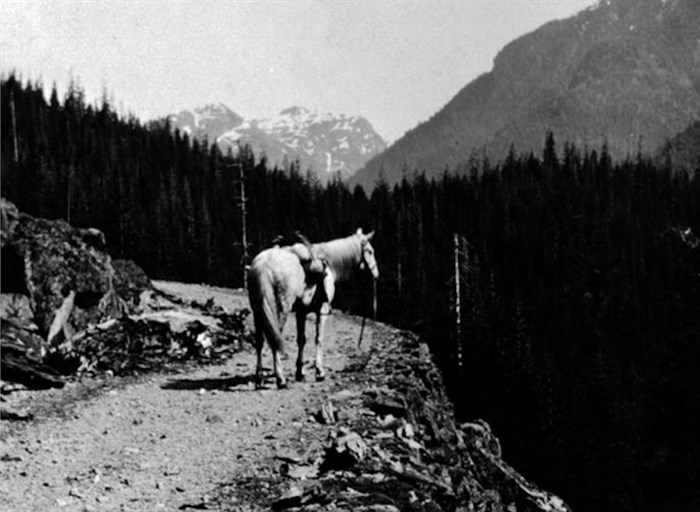

Gold was discovered in Rock Creek in 1859 so Edward Dewdney was recruited to build a 1.3 metre (four-foot) wide wagon road from Hope to those gold fields, which became the first leg of what became the province-wide Dewdney Trail.

While there was a trail through the mountains, the actual roadway only got built as far as Rhododendron Flats, near present day Manning Park. Resources were quickly diverted to the Cariboo Wagon Road through to the Barkerville gold fields.

READ MORE: BC’s first trans-provincial highway stalled before it reached the Okanagan

Not long after, in 1864, gold was discovered on Wildhorse Creek. There’s a national historic site there now that says its 5.5 km northeast of Fort Steele, which is east of Cranbrook.

Which means it was about as far away from BC’s capital in Victoria as anyone could get in Southern BC. It necessitated the crossing of several mountain ranges and raging rivers.

That meant the mining supplies to Fisherville, the first non-native settlement in the East Kootenays (also now a national historic site) that sprung up to service the gold fields, came along the Walla Walla trail from Washington State.

“Far away west on the Coast, British Columbia merchants fretted at the thought of their American counterparts growing fat forwarding supplies up the Walla Walla Trail to the miners at Fisherville,” says an article on the Virtual Crowsnest Pass website written by Donald Malcolm Wilson. “They agitated for access to the new bonanza, pointing out that the Colony, too, was losing money by not controlling trade in the area.”

The government did send a couple of survey parties out in the fall of 1864 to mark a path to the Rocky Mountain Trench. But, it wasn’t until the next year, when Dewdney was called in by Governor Frederick Seymour, did real work begin on the trail.

Workers set off from Fort Hope and hiked over the original Dewdney Trail through to Rock Creek (where the gold supplies had dwindled).

“Initially their supplies were packed by Stó:lo carriers but, much to Dewdney’s chagrin, these folks refused to venture down the Similkameen, so the party was forced to buy horses from the Allison family,” Wilson wrote. “They had to release the exhausted horses in the Kettle River valley near Rock Creek and, with the aid of some Salish porters, trekked to Christina Lake.”

From there they trudged up what is now the Santa Rosa Pass through the Rossland Range to Fort Shepherd.

That was a Hudson’s Bay Company fort that was built in 1858 at the mouth of the Pend d’Oreille River where it flowed into the Columbia River south of Trail (which took its name from these road building efforts) and is just north of the American border.

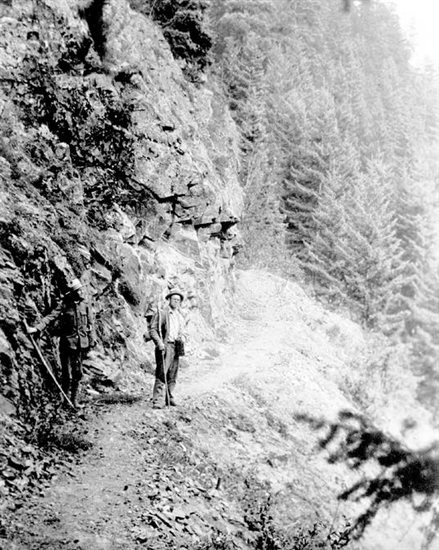

From there, Dewdney and a couple of volunteers explored eastwards to the find the best and shortest route though the mountains.

Ultimately they “blazed their way up the Pend d’Oreille to the Salmo River and then scrambled up the Lost Creek defile to o’er top the Selkirk’s Nelson Range by the Kootenay Pass, a difficult route likely chosen to satisfy Seymour’s expectation that the Trail be kept as short and as close to the Boundary as possible,” Wilson wrote.

That led them down to what is now Creston.

“Wading and slashing through the swampy bottoms of the Purcell Trench at the head of Kootenay Lake, the crew mounted the ancient Purcells by Duck Creek, followed the Goat River’s valley for a ways and finally hit the Walla Walla Trail at what is now Yahk in the Moyie’s valley,” Wilson wrote.

From there they pushed through to Fisherville and Wildhorse Creek.

“Having yielded somewhere between nine and fifteen million dollars in raw gold, the Wildhorse’s sands were rapidly playing out,” Wilson wrote. “Many miners had already rushed off to new strikes leaving only die-hards . . . to patiently wash away the last vestiges of Fisherville. Nonetheless, the Trail was to be built, for no one at the time knew that the big money had already been taken out of the Trench.”

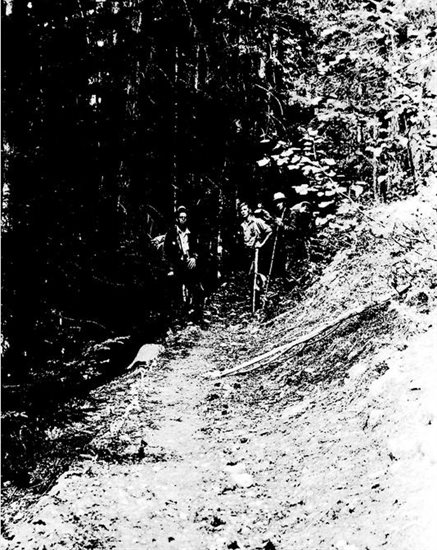

Dewdney hired a crew of unemployed miners, mostly Chinese, who headed back along the trail under the direction of William Fernie to expand it to the mandatory four-foot width.

Dewdney returned to his headquarters in Fort Shepherd and hired more men, segregating them so the Chinese worked eastward and the Caucasians towards the west.

The Dewdney Trail was, essentially, finished in 1866 at a total cost of $74,000.

“Even then, no bridges had been constructed. Trees blown down across the Trail and yearly wash-outs, especially in the swamps at the head of Kootenay Lake, were to require further expenditures,” Wilson wrote.

“Though the establishment of the Kootenay Post Office there in 1866 was to make Wildhorse the government outpost in the Trench, so remote and quiescent was the locale that the maintenance of the Trail could not be justified and, after a major clearing of the deadfall and brush on the difficult section between the Moyie and Fort Shepherd in 1875, it was allowed to revert to nature.”

And there it lay for decades with East Kootenay commerce being channeled through the U.S. The only way to get to Victoria was to take a month-long trek down to Portland and a steamer to Victoria.

READ MORE: How an Indigenous trail through Kicking Horse Canyon grew into a super highway

According to a BC Highways timeline compiled by Jeff Schlingloff in 2006-07, the Crowsnest Highway #3 was not developed until the 1920s.

Initially, he posted, “the Southern Trans-Provincial Highway from Vancouver, went through Spences Bridge to Merritt, south along the Coldwater River, then to Princeton, (initially via Coalmont).”

It took another 20 years to build the shorter Hope-Princeton section of the highway, completed in November 1949.

“This provided the direct highway link from the Fraser Valley to the Southern Interior across the North Cascade mountains, signalling the demise of the Kettle Valley Railway as the principle transportation route in Southern BC,” Schlingloff wrote.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Rob Munro or call 250-808-0143 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won't censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above. SUBSCRIBE to our awesome newsletter here.