Image Credit: Contributed by author

August 04, 2015 - 9:32 AM

“I had the ambition to not only go farther than man had gone before, but to go as far as it was possible to go.” ~ Captain James Cook, 1768

After the great spasm of the Second World War ground to a halt and the geopolitical landscape solidified into the Cold War, something else began that no one seems to notice anymore. Yet it's larger than all the imagined apocalyptia of our age, larger than the Manichean economic struggles of the 60s, the Malthusian Population Bomb of the 70s, the pseudo-scientific Nuclear Winter of the 80s, the Ozone Hole of the 90s, Peak Oil of the aughts, or the current cataclysmia de jour, Climate Change, formerly known as "Global Warming," formerly known as the "New Ice Age," formerly known as "weather." And when the history books of the middle to far future are written it is something that will, without the faintest shadow of a doubt, dwarf them all into insignificance.

On October 4, 1957, a polished sphere less than two feet across rose from the wreckage of the Nazi rocket program and burned through the skies in low earth orbit for 21 days before vaporizing on its way home. So began our Second Age of Discovery.

The launch of Sputnik heralded a crescendo of scientific advances that culminated in a footprint and a flag on Luna, a chunk of rock so close to earth that it affects our ocean tides and fires our poets' minds, and yet so far away and unattainable that it may as well have been the dim fringes of the Milky Way so far as everyone who went before us was concerned. I remember that evening in the summer of 69 when all the world was held in a moment of awe, when even as a prepubescent boy I grasped in some small way the weighty privilege of being here, in history, at that moment in time. No other generation will have that honour.

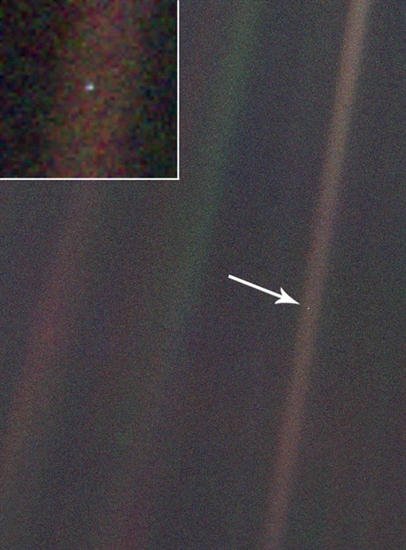

A decade after the Giant Step we launched Voyager I, which paused in its travels in 1990 to look back over its shoulder and send us the haunting image of a pale blue dot, shimmering in a sea of stars, six billion kilometres away, an image about which Carl Sagan wrote:

Earth is the barely visible centre right dot, captured in a striation of light from the sun reflecting on the camera lens.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

"That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives... There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world."

And then we stopped. Or maybe just paused to take a breath. Or maybe we are simply gathering ourselves for the next leap, absorbing information piecemeal before reaching silver fingers outwards again. But I fear something else has happened in the interim.

I fear we have become obsessed with our pale blue dot, casting our eyes downward, wracked with guilt for emerging from a state of nature, imagining a new apocalypse around every turn of the globe. We worship scarcity under the guise of conservation and wring our hands over resource depletion, and we do it all while floating in an infinite sea of infinite resources. The building blocks for all the water, all the air, all the food and all the materials we could ever use in a trillion generations are a stone's throw away when we get around to looking upwards again.

Almost unnoticed amidst the internet mobhunt for a lion-killing tooth doctor and other Great Issues of our day, we discovered Kepler 452b (https://www.nasa.gov/keplerbriefing0723), an earth-like planet not too far away that might support life.

An artist's concept of Kepler-452b in orbit around its star Kepler-452.

Image Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

A few days after that our New Horizons spacecraft flew within a hair's breadth of the frozen glaciations of our solar system's outermost planetoid, sending us humanity's first close images of hitherto unknown Pluto. A couple of months before that we learned that the EmDrive, a theoretical propulsion system similar to Star Trek's "Impulse Drive," will probably actually work and be able to carry us to the moon in four hours or Pluto in 18 months. We may even have discovered, almost by accident, a mechanism for faster-than-light travel in our tinkerings.

While this may seem today the stuff of science fiction, it is well to remember that many of the people who watched the flickering black and white vacuum-tube images of Neil Armstrong in 1969 were born before the Wright Brothers pasted together rags and sticks and flew for 12 rickety seconds on Man's first powered flight. Many of us reading this today will be alive in 2034, when we will be as far away in time from the moon landing as the moon landing was from Kitty Hawk. The EmDrive or something like it could be operational within our lifetime if we put the same energy into it that we put into the Apollo mission to the moon, and if we do, some of us will be pioneers again, where we humans belong, doing what we humans are meant to do. Earth will always be our home, but it is not the totality of our future.

"Flight by machines heavier than air is unpractical and insignificant, if not utterly impossible." ~ Dr. Simon Newcomb, Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy at Johns Hopkins 1902

In 2012 Voyager I left the heliosphere and entered the dense plasma fields of interstellar space, beyond the reach of our sun's solar wind, in the region between the stars. Today it is almost 20 billion kilometres away, hurtling at 62,140 kilometres per hour, headed vaguely toward a star with a numerical name in the constellation of Camelopardalis, where it will arrive in about 40,000 years. Were it to turn and look back again today it could no longer see us against the vast and stunning backdrop of one arm of our small galaxy of 300 billion stars.

Someday, maybe far in the future, maybe much sooner, we'll catch up to it and we'll pass it, and we'll marvel at our own audacity.

I wish I could be there.

— Scott Anderson is a Vernon City Councillor, freelance writer, commissioned officer in the Canadian Forces Reserves and a bunch of other stuff. His academic background is in International Relations, Strategic Studies, Philosophy, and poking progressives with rhetorical sticks until they explode.

News from © iNFOnews, 2015